Introduction

Female Community Health Volunteers (FCHVs) are at the found actions of Nepal’s primary health care system and are a key referral link between a community and health services, supporting grassroots health-seeking behaviour change on reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health.1 FCHVs are self-motivated women of the local community selected by Health Mothers Group (HMG), who commit themselves to work as volunteers for a certain period and have received training as per the primary curriculum of FCHV.2,3 More than 50,000 FCHVs work on health promotion and disease prevention, and many of their health interventions have improved maternal and child health outcomes. These improvements can be seen in the Nepal Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS) data of 2006-2011, revealing that many interventions implemented through FCHVs had an increasing trend. The health promotion activities conducted by FCHVs related to counselling pregnant women on side effects of family planning commodities and providing counselling to pregnant women on birth preparedness shows greater FCHVs contributions, which was 65% in 2011 on counselling pregnant women on side effects of family planning commodities and 76% on birth preparedness counselling to pregnant women.4 The role of FCHVs has also been crucial to reducing child mortality by two-thirds in 2015 compared to 1990 in Nepal.5

Despite all these achievements, FCHVs are volunteers with no minimum educational requirements, limited training opportunities, infrequent and inconsistent supervision, receive intermittent and inconsistent incentives, and have no career advancement opportunities.6 FCHVs are overburdened due to programmatic defragmentation and are obliged to perform multiple tasks for similar activities. They can provide counselling, distribute health commodities, and refer women and children to health facilities as required. Hence, they need to be trained separately with action cards, job aid tools, treatment protocols and counselling guidelines.4 This calls for an integrated FCHV program with the promotion of FCHVs as health promoters and a bridge between community and health facilities but not service providers except in some remote areas. There is minimal evidence regarding the views and experiences of FCHVs and how the work of FCHVs is viewed and experienced by service users.7

Information, Communication and Technology (ICT) has been successfully used in countries with similar health systems and challenges with community health volunteers, providing evidence that mobile health (mHealth) improvements are possible.8 Multiple systematic reviews have assessed the impacts of mHealth interventions in low resources settings, suggesting that mobile technology for communication support has led to substantial improvements in the quality of interaction and discussions.9 With the exponential rise of phone ownership, mHealth interventions are being used to support FCHVs in their job through increased access to information, updates and support, with positive results. However, the changing context, health practices and services updates, and FCHVs’ ability to engage with communities and communicate health information required strengthening.3

The objective of this study was to examine the impact of using Mobile Chautari- a mHealth innovation aimed at FCHVs in Nepal, to improve the quality of their health communication and engagement with communities. The study also aimed to bridge the gap between FCHVs and communities through innovative mobile phone-based solutions.

Subjects and methods

Study setting

The study was conducted in the three districts of Nepal: Tehrathum, Rautahat and Darchula. The districts were selected based on the key reproductive, maternal and child health indicators and Human Development Index (HDI) scores. This selection is also considered a representation of every ecological zone in Nepal - Hill, Mountain and Terai. The research took place in 15 municipalities across three intervention districts- Tehrathum (six), Rautahat (four) and Darchula (five).

The mHealth intervention, Mobile Chautari

Mobile Chautari was designed as a job aid that FCHVs can use to strengthen their health communication skills and enhance the quality of interactions they already had in their communities. This included a two-day training for FCHVs, audio content played to beneficiaries via FCHVs’ mobile phones delivered via an Interactive Voice Response (IVR) system and the local health facility’s speaker, and a set of printed prompt cards across thirteen key health topics. A five-month Mobile Chautari intervention period (October 2019 to February 2020) followed the FCHVs training, which allowed FCHVs to conduct up to five monthly HMG meetings using Mobile Chautari, generally at least an hour-long, though FCHVs are typically less active during the festival month of October.

The two-day training introduced FCHVs to Mobile Chautari, how to use it in community interactions, particularly in Health Mothers’ Group (HMG) meetings and how and why it would help improve their interactions with the community and ultimately the community’s health. A total of 810 FCHVs (Tehrathum-387; Darchula-217; and Rautahat-206) were trained on how to follow Mobile Chautari prompt cards and access its audio content, which was produced in three languages – Nepali, Bajika and Doteli – to align with the most spoken languages in the three districts of Tehrathum, Darchula and Rautahat. Mobile Chautari also used a simple and easy-to-remember format for FCHVs (“Ke? Kina? Kasari?” - “What? Why? How?”) to structure their interactions and which links to the audio and prompt cards. A hypothetical central character named ‘Dr. Asha’ (the name ‘Asha’ means hope in English) was chosen as the “doctor” who delivered all core messages. Mobile Chautari uses audio drama in two parts and a simple three-question model for FCHVs to help lead a constructive discussion.

Mobile Chautari used an IVR system in which the content was stored on a central server and accessed via toll-free numbers on either the NT (Nepal Telecom) or Ncell mobile networks from any mobile phone (Figure 1). All calls to the toll-free numbers were logged and could be used to measure usage of Mobile Chautari as a whole and to measure call volumes for individual health topics. Each language had its own toll-free numbers and a different number for NTC and NCELL to avoid confusion among FCHVs selecting the language and mobile network within the IVR system.

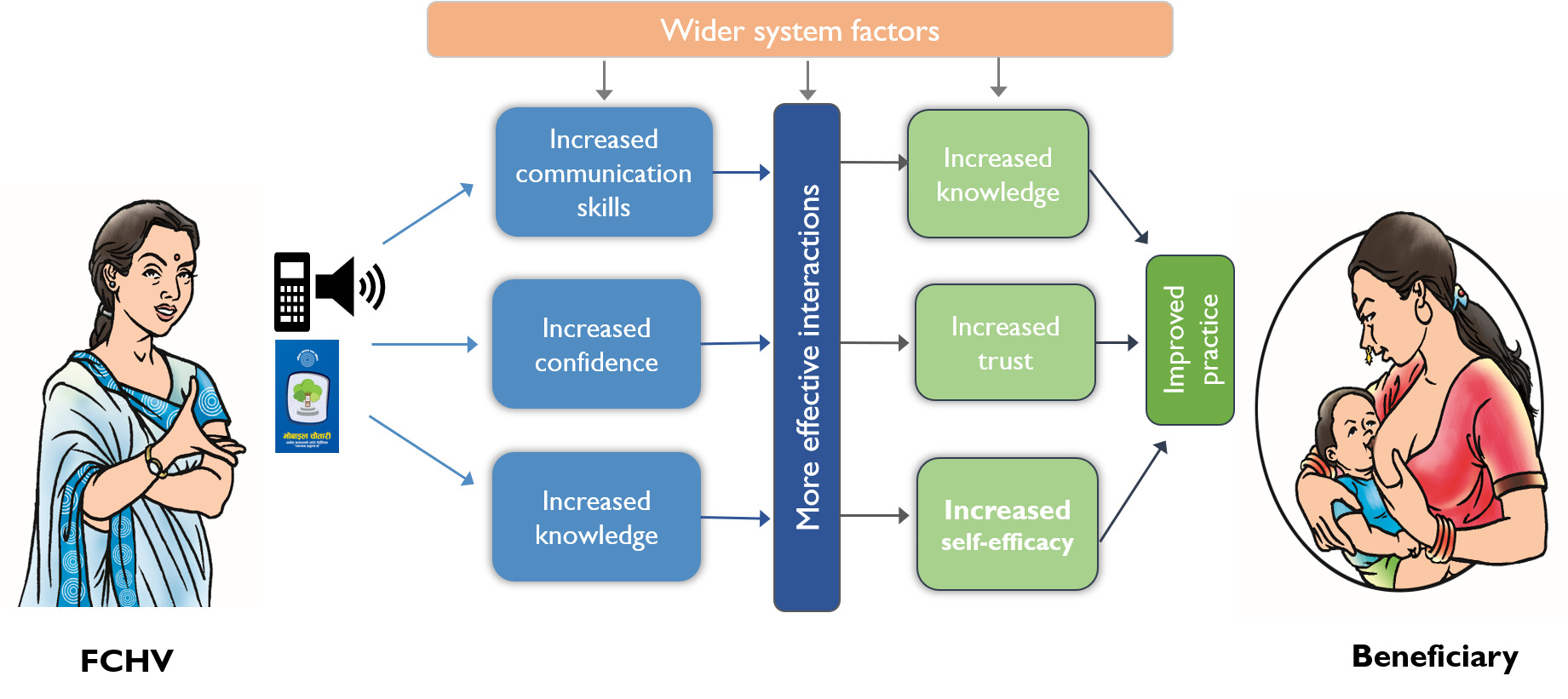

The project’s theory of change (Figure 2) posited that if FCHVs have access to a mobile phone and engage with Mobile Chautari, it will improve their health communication skills, increase their motivation and confidence around their role and improve their understanding of key health topics, which will lead to effective interactions with community members, particularly in existing HMGs, and thereby contribute to improving community health in the long run.

Sampling methodology

We conducted a qualitative study employing in-depth interviews (IDIs), focus group discussions (FGDs) and observations. Respondents included FCHVs, pregnant women and mothers with children under five years old, mothers-in-law, and health facility staff (i.e., staff that FCHVs work directly with) who participated in the Mobile Chautari intervention. This qualitative study was designed to understand FCHV’s uptake and engagement with the Mobile Chautari, their perceptions of how the tool affected their interactions with community members and community members’ perceptions and experiences of Mobile Chautari (Table 1).

FCHVs were categorized into high, medium, and low users of Mobile Chautari based on the number of calls logged in the IVR data and six from each high and medium and four from the low group were selected as a representative sample. To understand the variation in adoption and usage of Mobile Chautari, FCHVs were also selected based on their educational attainment and age. Selected FCHVs were asked to provide the list of their beneficiaries from their monthly mothers’ group meetings who attended the meetings with Mobile Chautari. Random sampling from these lists was used to select the beneficiaries. The study included 78 IDIs, 12 FGDs and six observations of HMG meetings (Table 2).

Ethics considerations

The study was approved by the Nepal Health Research Council (NHRC) Ethical Review Board (Reg. no. 643/2019). Participants were briefed about the study and their role in it, assured of the confidentiality and anonymity of their data, and written consent for community participants less than 18 years was sought from the parents/caregivers. The data obtained from the IDIs, FGDs and observations were anonymized, transcribed verbatim, translated into English, and analyzed manually by developing a coding framework and identifying emerging themes to meet the study’s objectives.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants

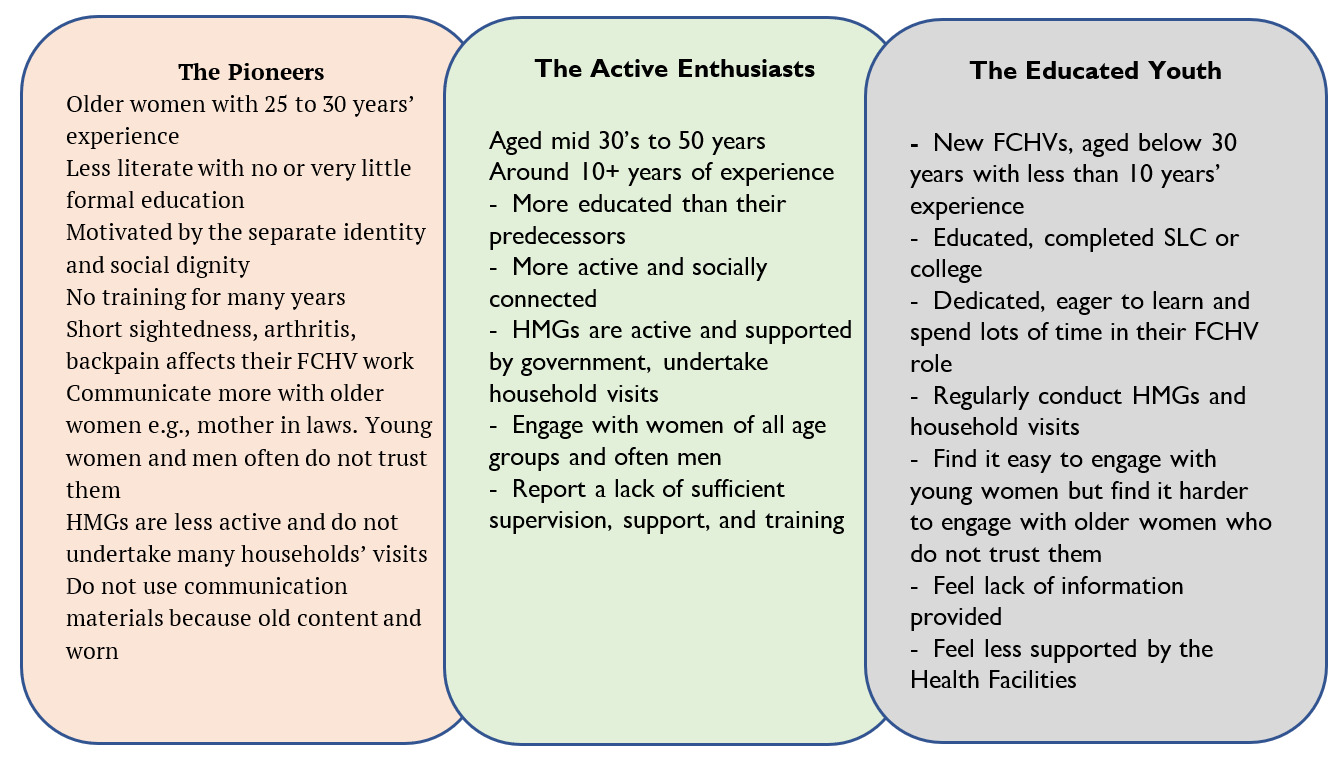

FCHVs in the study districts were from diverse ethnic and caste backgrounds, including the ‘upper caste’ Brahmin, Chhetri, Janajati and Dalits, which reflected the diversity of the population within the districts. Considering FCHV’s age, education, training, support, and engagement with communities, the research found three emerging segments of FCHVs related to their background and ability to communicate effectively with communities (Figure 3). a) The pioneers: First-generation FCHVs who have been serving for more than 20 years, have little or no formal education, mainly communicate with older women like mothers-in-law in the communities and have high individual barriers to engaging and communicating with communities (such as mobility issues). Found in all three districts of the research, they were slightly more common in Rautahat; b) The active enthusiasts: Second-generation FCHVs, comparatively young and more educated than the first-generation FCHVs, have support from other sources, e.g. I/NGOs working in the localities, more confident and engaged with communities but still report challenges including insufficient supervision, support and training to meet their needs. They were found more commonly in Darchula and Tehrathum; and c) The educated youth: young women who have been recruited in the past five to seven years, most of them have completed secondary education with many having completed school certificate exams and have gone to college. These young women are less experienced but very active and interested to learn their roles. Their engagement with communities is higher due to their proactive communication, and they were mostly found in Darchula and a few in Tehrathum.

Mobile Chautari was preferred to existing print communication materials

Across the intervention period, backend data from the IVR system was analyzed to examine the take-up and use of Mobile Chautari, which showed that the highest proportion of Mobile Chautari users was from Tehrathum and Darchula the lowest was from Rautahat. These findings match the formative research (conducted during the project’s inception), which indicated that take-up of the service was more likely to occur in Tehrathum and Darchula owing to higher mobile network access and FCHVs were more comfortable with mobile phone technology.

FCHVs had replaced the use of other communication materials in mothers’ group meetings with Mobile Chautari. FCHVs had previously reported that flip charts and posters were challenging to carry around and were no longer interesting to community members. Mobile Chautari had helped overcome this issue. Interviews with beneficiaries and health facility staff, who reported participating in several meetings where Mobile Chautari was used, supported this:

“When we talk about this in our meeting, [FCHVs] said that they have used Mobile Chautari at least twice or three times. When women come here for check-ups with their babies, we ask them where and how they learned about bringing their babies for a check-up. They answered that they learned from HMG meetings through Mobile Chautari”-Health facility staff, Tehrathum

Even though the Mobile Chautari was primarily meant for use at HMG meetings, a few FCHVs also reported using it outside HMGs, indicating that they found it helpful in other interactions, such as household visits.

FCHVs recognized the value of Mobile Chautari and the role it played in helping them to facilitate more effective discussion in HMGs

Interviews with FCHVs suggest that Mobile Chautari helped them learn the value of effective communications and provided them with ways to make HMG meetings interactive and practical, although using the mobile phone-based system and connecting mobile with a speaker was new. While it was difficult for FCHVs to talk about how their knowledge of effective communication had changed, they provided practical examples of how adopting the ‘what, why and how’ method – the facilitation module used in Mobile Chautari – provided more structure to HMG meetings.

“The way of closing the [HMG] meeting has changed. We used to close the meeting by telling them what topics we discussed today. But now, after listening [to] the Mobile Chautari content, we discuss the topics from the content and discuss what we learned and what members of the mothers’ group learned”- FCHV, medium user, Tehrathum

FCHVs felt that Mobile Chautari influenced their communication skills and confidence to talk about health issues and communicate effectively with their beneficiaries. Many of the mothers and mothers-in-law reported an increase in attendance and positive changes to the structure and dynamics of HMG meetings. The FCHVs also reported that the content of Mobile Chautari, which was linked to the health knowledge and understanding they learned during their training, reminded them what to discuss in meetings, also helping them to feel more confident.

“The communication skill has increased compared to before. Before, I could not even speak [at HMG meetings]. It was difficult for me even to give my introduction, I used to cover my face. But it is very easy nowadays”- FCHV, Medium user, Darchula

As seen in the quote below, heath staff in the intervention districts also emphasized positive changes in FCHVs’ confidence. According to them, Mobile Chautari acted as a catalyst to make people listen to health content and a tool for boosting confidence among FCHVs.

“Before, FCHVs were afraid to speak for the fear they would say something wrong. They now have the confidence to say what they know in HMG meetings in front of health workers, and we support them when we attend meetings”- Health facility staff member, Darchula

Influence of Mobile Chautari on the quality of interaction with beneficiaries

Most FCHVs emphasized that after the introduction of Mobile Chautari, the discussion in HMGs shifted to health issues compared to before, when discussions mainly were about savings. In addition to the FCHVs reporting their higher confidence levels, findings suggest that beneficiaries also experienced positive changes due to interactions and discussions with FCHVs. Mothers and mothers-in-law also said that FCHVs now mainly discussed health issues, and as a result, the meeting had become longer, with more participation from diverse people and greater interest and willingness to attend meetings:

“Didi [sister] used to sit in the meeting for only 2–3 minutes, but now she sits for about 1–2 hours. We have a meeting from 1 pm to 3 pm. Sometimes it lasts up to 4[pm]”-Mother of a child under five years, Darchula

Another explains,

“HMG meetings might sometimes go off-topic, but with Mobile Chautari, they have proper guidance. They know how to ask questions, hold discussions, and end them, and there is not much out-of-context discussion. It is now time-oriented, and they are relaxed”-Health facility staff member, Darchula

FCHVs said that whilst communities trusted them before Mobile Chautari, Mobile Chautari has helped them gain recognition as a reliable source of health information because the audio content backed up the information they imparted. FCHVs and HMG members reported that there was now increased respect and recognition of FCHVs as health promoters. Health facility staff also stated that FCHVs’ use of Mobile Chautari meant that community members trusted them more than when they were imparting information themselves.

[Reporting beneficiaries’ perceptions of her role as an FCHV] “Yes, we used to believe her, but we believe her more now after we were made to listen to Mobile Chautari”-Mother of a child under five years, medium user, Tehrathum

Another FCHV from Rautahat also explains, “As they listen [to] Mobile Chautari, [meeting attendants] talk more. Earlier, we had to say everything orally, and they did not believe it as much. Now, they trust us as everything is live from Mobile Chautari through mobile phones. Trust is regained, and they understand it as well” (FCHV, medium user, Rautahat).

FCHVs felt Mobile Chautari was an essential facilitator in improving their credibility and engagement with pregnant women, mothers and communities and helping them engage with health information. However, it had a lesser impact on helping mothers-in-law engage with newer health information or shifting their beliefs about health. Despite this, mothers-in-law supported younger women in attending check-ups and listening to the FCHVs.

Discussion

This study has provided insights into using a mHealth intervention, Mobile Chautari, and how it helped FCHVs improve their communication skills as community health promoters. The study reported how FCHVs and their beneficiaries accepted Mobile Chautari to improve health outcomes by increasing understanding and the uptake of safer and healthier practices during pregnancy, delivery, and early childhood. Our findings from interviews, discussions and observations demonstrate that Mobile Chautari was used by most FCHVs participating in the project. Most of the FCHVs felt that using Mobile Chautari had helped them learn the value of effective communication with beneficiaries and improved their confidence and facilitation skills to discuss health issues and communicate with diverse clients. In doing so, Mobile Chautari bridged the gap between FCHVs and communities, as FCHVs during formative research reported having less trust from beneficiaries due to their limited knowledge of health-related issues and communication skills.

The positive results of Mobile Chautari resonate with similar findings from an evaluation of mHealth communication tools for community-based health workers in other Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs). They have shown the benefits skilled community-based health volunteers supported by a well-researched and developed mHealth tool can have on the health of mothers and children in terms of increased uptake of routine immunization, breastfeeding, infectious disease prevention and control, increased uptake of health services and family planning, reductions in maternal and child morbidity and mortality, and increases in family planning.10,11 Based on the evidence about the effectiveness of mobile-phone-based interventions among the community health volunteers, a mobile-phone-based mhealth intervention in India was implemented, which also showed that the use of innovative audio-visual aids made a positive contribution to the interactions between frontline health workers and beneficiaries.12,13 The findings of our study are also consistent with the findings from the evaluation of the SafeSIM pilot an mHealth intervention to improve maternal health care in Baglung district of Nepal. The SafeSIM evaluation found that FCHVs had a high acceptance of the technology and were willing to use it. Also, FCHVs reported that the use of the mHealth tool increased the frequency of contact with mothers and newborns, supported more regular home visits to provide counselling services to pregnant women and new mothers, increased a sense of responsibility among FCHVs, and created a sense of achievement provided by immediate acknowledgement of their work by communities and health workers.14 A qualitative study in Syangja, a hilly district of Nepal, explored using a mobile phone to improve community-based health and nutrition service utilization and reported that reminders and health information delivered by text messages were acceptable and well-used by the communities.15 A randomized control trial in the Dhanusha district of Nepal of an intervention that built communication capacities of FCHVs alongside a text messaging service to expectant mothers to improve gestational weights and haemoglobin levels found that the intervention had a positive effect on these outcomes.16 Two different studies from Tanzania have shown an increase in ANC visits and increase in skilled health personnel attendance for childbirth as a result of a text messaging service aimed at pregnant women.17,18 Our findings are also consistent with a qualitative study conducted in two states of India to improve health care delivery using mobile phone among health workers and beneficiaries, which showed that mHealth interventions were acceptable to the CHWs and tat the intervention improved the status in the communities where they worked, improved the performance of CHWs, and led to reduced information barriers and increased the uptake of healthier behaviours amongst beneficiaries.19

This study has demonstrated the benefits of Mobile Chautari on improving the quality of health interactions at HMG meetings and during household visits: discussion is structured, community members are engaged, and they trust FCHVs to provide accurate health information. This is very encouraging considering the Mobile Chautari was introduced only three months without any incentives. Mobile Chautari was developed under the leadership of the Nursing and Social Security Division (NSSD) but was not formally integrated into the health facility and supervision system. The FCHVs determined how they wanted to use it, ensuring that uptake was genuinely voluntary. Although the intervention timelines did not allow for a complete impact assessment on health outcomes, there are encouraging results. In the short period, the study has shown the potential of Mobile Chautari and how it could support positive behaviour change. Sustained implementation complemented by a robust evaluation could examine the tool’s intermediate outcomes and longer-term causal effects.

Limitations

The project timeframe was relatively short, meaning that FCHVs could run a maximum of five HMG meetings. As the meetings are monthly, there was a long period between Mobile Chautari in the ideal locations (FCHVs were trained primarily to use Mobile Chautari in HMG meetings but encouraged to use it in other interactions with clients). After the initial training on Mobile Chautari, there was a long holiday festival in Nepal during which HMG meetings were unlikely to happen.

Conclusions

Mobile Chautari is based on the learning from similar long-running interventions in India for ten years.19,20 Each intervention was developed through in-depth research and evaluation to ensure it continued meeting the health workers’ needs and the women and communities they work with. The learning from these projects helped inform the research and development of Mobile Chautari. The uptake of Mobile Chautari has also shown encouraging results among FCHVs in Nepal. Mobile Chautari appears to be a promising way to communicate health-related information and communicate with diverse clients. This paper offers a significant opportunity to hear directly from the FCHVs, the foundation of the Nepalese public healthcare system and provide essential services to its rural communities. We believe that the study findings have implications for similar kinds of mHealth interventions in other similar settings.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the participants for their valuable time and for sharing their experiences with us. We also extend our gratitude to the Director General of the Department of Health Services (DoHS) and other Technical Advisory Group (TAG) members who provided valuable comments and inputs throughout the project. We also thank members of the mHealth study team for research assistance; in addition to the named study authors, other team members who contributed to data collection and/or study administration.

Funding

This material has been funded by UKaid from the UK Government; however, the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s policies.

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization, data screening, inclusion and extraction and manuscript drafting. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors completed the Unified Competing Interest form (available upon request from the corresponding author) and declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Nepal Health Research Council (NHRC) Ethical Review Board (Reg. no. 643/2019).

Correspondence to:

Anju Bhatt, MPH, Research Manager, BBC Media Action, Sanepa Heights Rd, Lalitpur, Nepal-44600; anju.bhatt@np.bbcmediaaction.org