Vaccination remains one of the most effective strategies to prevent infectious diseases and reduce child mortality. Yet, in 2024, 14.5 million children aged 12–23 months worldwide had not received any doses of essential vaccines, including those against diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis.1 In Africa, despite initiatives such as the “Big Catch-Up,” more than 5 million children were identified as having “zero doses” in 2024.2 In some parts of sub-Saharan Africa, non-vaccination prevalence reached 75.5%, driven by poverty, remoteness from health facilities, and cultural beliefs.3

In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), the situation remains concerning. In 2024, 9.3% of children aged 12–23 months had not received any vaccine doses, while 40.9% were under-vaccinated, particularly among displaced and refugee populations.4 Although administrative coverage reaches 92.0% for some antigens, discrepancies between official data and adjusted estimates highlight challenges in data quality and equitable access.5,6 These national figures mask provincial heterogeneity, where local health infrastructure and sociocultural dynamics strongly influence outcomes.

Factors associated with non-vaccination include socioeconomic, cultural, and geographic barriers.7 Children from low-income families, whose mothers have low education, and those born at home without postnatal care often miss awareness campaigns and routine programs.8 Ignorance of vaccination schedules, fear of side effects, and indirect costs further limit access.7,9–13 Births outside health facilities and lack of postnatal care weaken coverage.14–16 Geographical constraints, vaccine stockouts, and shortages of qualified personnel hinder campaigns,17–19 while inconvenient health center hours complicate service availability.16

To address these challenges, WHO and UNICEF have implemented strategies such as the 2030 Agenda for Immunization,20 aiming to improve equity, halve the number of unvaccinated children, and introduce new vaccines.21 UNICEF emphasizes a multisectoral approach, integrating immunization with nutrition, maternal health, and safe water programs.22 Nonetheless, fragile health systems, armed conflict, misinformation, and geographical barriers persist.23 The COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated these difficulties, contributing to stagnant coverage and rising numbers of unvaccinated children.24

Against this backdrop, Lomami province represents a critical case study. Characterized by limited health infrastructure, logistical challenges, and remote rural populations, Lomami illustrates how structural weaknesses intersect with socioeconomic and cultural barriers to produce persistent gaps in coverage.6,9 Studying Lomami provides insights into localized determinants of non-vaccination and informs broader strategies to improve equity in fragile contexts. This study therefore aims to identify factors associated with the non-vaccination of children aged 12–23 months in Lomami during 2023, moving beyond national averages to highlight specific barriers undermining uptake.

METHODS

Study framework

This study is part of the 2023 immunization coverage survey, focusing on Lomami province, which is characterized by geographic and demographic diversity. With a predominantly young and rural population, the province faces challenges such as malnutrition, low birth registration rates, and low immunization coverage. Only 27.0% of children aged 12–23 months are fully vaccinated, underscoring serious inequalities in healthcare access.

Study design

This is a secondary analysis of data from the vaccination coverage survey conducted in 2023 by the School of Public Health of the University of Kinshasa across all 26 provinces of the DRC, including Lomami.

Sampling

The survey included 1,580 children aged 12–23 months, selected from 2,630 households across all health zones in Lomami. The difference between households and children reflects that not all households had eligible children.

The statistical unit was an unvaccinated child aged 12–23 months residing in Lomami province. Children were included with parental consent; those who had left the province or lacked consent were excluded.

A three-stage cluster probability sampling method ensured representativeness by health zone (HZ). Sixteen surveys were conducted, each focusing on one HZ and its health areas (HAs).

-

Stage 1: Five health districts (HDs) were randomly selected within each HZ.

-

Stage 2: 30% of avenues or villages within each HD were chosen randomly.

-

Stage 3: Systematic sampling of 34 households with at least one eligible child was conducted in each HD.

Village information was obtained from local authorities and cadastral surveys. Block-based maps facilitated household identification with community liaison support. Interviews were conducted with heads of households and mothers or caregivers.

Sampling weights were calculated based on selection probability at each stage, and cluster adjustments were applied to account for intra-cluster correlation, strengthening statistical validity.

Study variables

-

Dependent variable: – Non-vaccination, defined as a child aged 12–23 months who had not received any doses of the diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (DTP) vaccine. – Partial vaccination (one or two doses) was examined descriptively but excluded from regression models.

-

Independent variables: – Maternal age, marital status, education, occupation, religion. – Child’s age and sex, respondent–child relationship. – Household socioeconomic status (wealth quintiles), number of children in care. – Socioeconomic status derived from a composite wealth index based on household assets and living conditions.

-

Confounders and diagnostics: – Potential confounders identified a priori. – Collinearity diagnostics performed to ensure model robustness.

Data collection

Data were collected using a combination of structured questionnaires, in-depth interviews, direct observation, and document review. Interviews were conducted with household heads, mothers or primary caregivers, and relevant health-care staff to obtain information on child and household characteristics, health-service use, and vaccination history. Children’s vaccination status was verified primarily through inspection of vaccination cards and health-facility records; where these were unavailable, parental recall was used.

Prior to data collection, formal authorisation was obtained from the Ministry of Public Health, relevant health-zone directorates, and community leaders. Community awareness and sensitisation sessions were held to explain the objectives of the study and to promote informed participation. Data were collected digitally using Android tablets programmed with SurveyCTO, enabling real-time data capture and supervision. Field supervisors monitored data quality continuously, and household locations were georeferenced to allow subsequent spatial analyses. Completed questionnaires were securely transmitted to a protected server, and for the present analysis, the Lomami dataset was extracted from the national survey database for secondary analysis.

Data analysis

Data processing involved multiple quality-control procedures, including field checks, close supervision, data cleaning, and secure data management. Analyses were restricted to children aged 12–23 months. Descriptive statistics were used to summarise the data, while inferential analyses included chi-square tests and multivariable logistic regression models to examine factors associated with the outcomes of interest. Results are presented as adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 25.0, with appropriate consideration of the sampling design.

Missing data were assessed through sensitivity analyses. Variables with substantial non-response, such as maternal education (missing in approximately 43% of observations), were retained in the models by treating missingness as a separate category. The analytical strategy involved initial univariate analyses to identify variables associated with the outcome at a significance level of p < 0.20, followed by inclusion of these variables in multivariable models. Potential confounding was evaluated by examining changes in odds ratios, and multicollinearity was assessed using variance inflation factors.

Several limitations were recognised. These include reliance on parental recall when vaccination cards were unavailable, potential variability in measurement practices across health zones, and the absence of some potentially important variables, such as distance to health facilities and household income. These limitations are acknowledged to enhance transparency and to guide interpretation of the findings.

Ethical considerations

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Public Health, University of Kinshasa (ESP/CE/148/2025), with authorizations from administrative and health authorities. Informed oral consent was obtained, justified by limited literacy, and explained in local languages to ensure understanding. Confidentiality was maintained through anonymization. For secondary analysis, only anonymized data were used, consistent with international ethics norms recognizing oral consent in low-resource settings where written documentation is impractical

RESULTS

Sociodemographic characteristics

As shown in Table 1, most respondents were aged 20–24 years (28.4%), and nearly all were the child’s guardian (96.6%). The majority reported being single (95.1%). Educational attainment was low, with 44.2% completing primary school and 10.9% reporting no schooling; however, 43.0% did not provide education data, representing substantial missing information. Occupation was dominated by farming and livestock breeding (65.4%). Religious affiliation was diverse, with revival/independent churches most represented (38.0%). Socioeconomic status was skewed toward the lower categories, with 40.7% of households classified as low or very low.

Non-vaccination rates

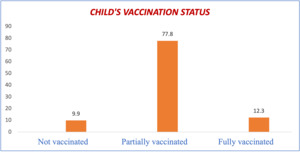

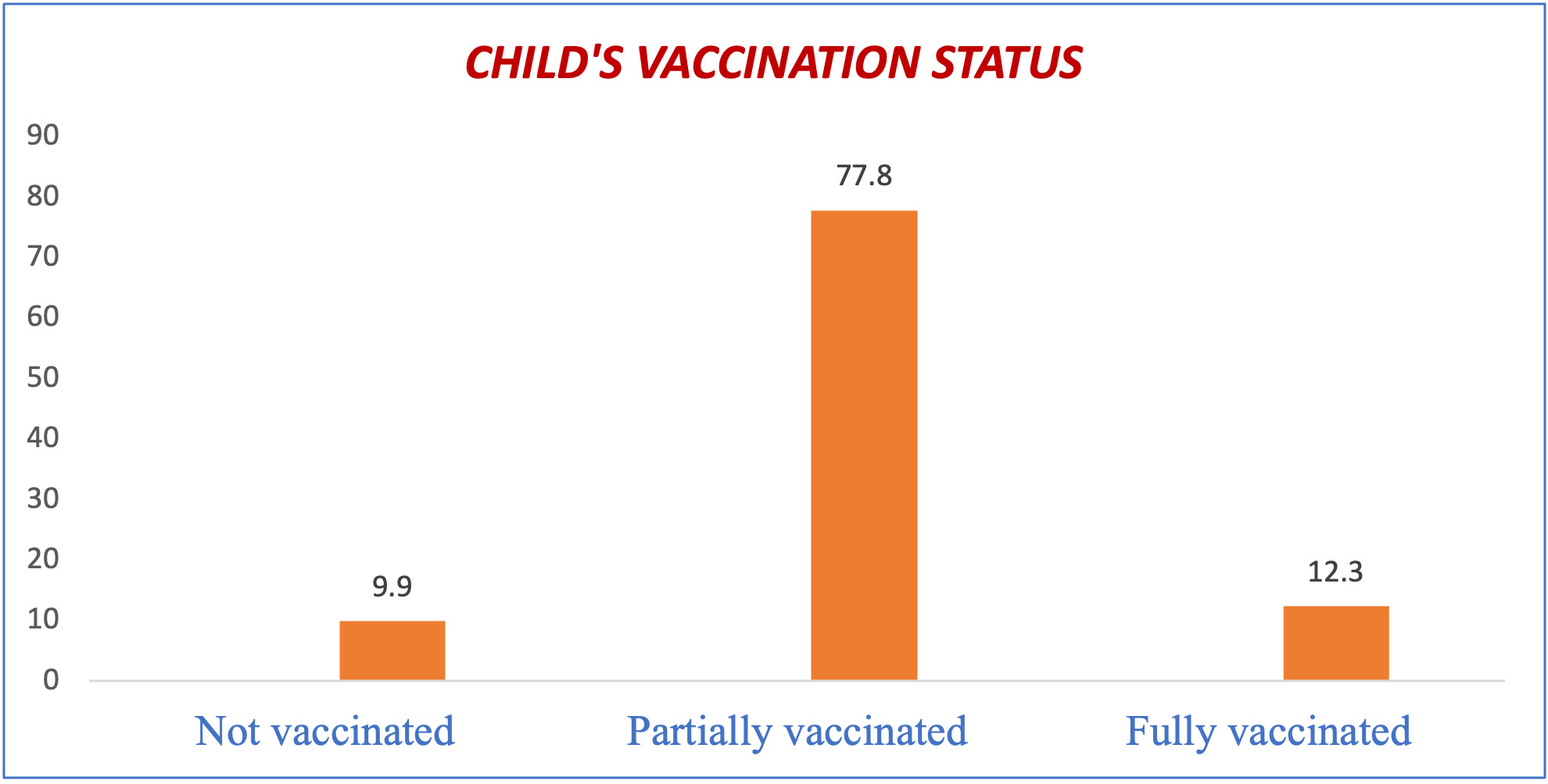

Figure 1 shows that approximately one in ten children aged 12–23 months was unvaccinated in Lomami province in 2023, highlighting persistent gaps in coverage despite national programs.

Barriers to vaccination

As presented in Table 2, nearly half of mothers of unvaccinated children (45.5%) cited vaccine unavailability. Other barriers included distance to vaccination sites (18.2%), lack of awareness of schedules (18.2%), long waiting times (27.3%), doubts about vaccination (39.4%), and ignorance of its importance (23.5%). These findings indicate both supply- and demand-side constraints.

Satisfaction with services

Table 3 shows high overall satisfaction, with 72.3% “very satisfied.” Dissatisfaction was linked to vaccine shortages (27.8%), unsuitable facility hours (22.2%), poor staff training (33.3%), and disrespectful behavior (16.7%).

Regression analysis

As shown in Table 4, children from very poor households had significantly higher odds of being unvaccinated (adjusted, aOR = 1.65, 95% CI: 1.39–1.96, p = 0.033). Other associations, such as marital status and maternal education, showed wide confidence intervals and implausibly large odds ratios, suggesting model instability due to sparse data. Civil servant status was associated with higher odds (aOR = 2.43, p = 0.004), though small sample size limits confidence. Religious affiliation showed no consistent associations.

DISCUSSION

Key findings

This study examined factors associated with the non-vaccination of children aged 12–23 months in Lomami province in 2023. Approximately one in ten children was unvaccinated. Reported barriers included vaccine unavailability (nearly 50%), long waiting times (30%), and maternal doubts about vaccination (40%). Multivariate analysis indicated that children from very poor households were at greater risk, as were those whose mothers were divorced or had no schooling. However, some associations—such as the apparent protective effect of civil servant status—should be interpreted cautiously, as they may reflect residual confounding or small subgroup sizes rather than robust causal mechanisms. These findings point to structural challenges including logistical problems, remoteness of vaccination sites, and limited maternal information.10–13 The economic insecurity of divorced mothers,12 low maternal education,25 and job security26 were linked to vaccination outcomes, though these explanations remain speculative given the absence of qualitative data.

Exploring findings in the literature

The non-vaccination rate of nearly 10% highlights persistent coverage gaps. Structural and behavioral barriers such as vaccine shortages, remoteness, long waiting lines, maternal beliefs, and lack of information were central. Yet, the measurement of “maternal beliefs” relied on a single survey item, restricting interpretation and complicating conclusions about vaccine hesitancy. Future studies should incorporate more nuanced measures of vaccine confidence.

Comparable findings have been reported elsewhere. UNICEF (2022) noted that 12% of children in the Sahel were unvaccinated, largely due to limited healthcare access. In Ethiopia, GAVI (2020–2024) reported 9.8%, influenced by regional disparities and maternal education. In the Central African Republic, WHO (2020) observed 11%, linked to political instability and vaccine stockouts. In Haiti, WHO (2023) reported 14%, driven by economic constraints and hesitancy.11 While these comparisons provide context, Lomami’s findings underscore the need to examine local health system weaknesses—such as fragile supply chains and limited outreach capacity—that directly shape vaccination outcomes.

National data from the DRC 2024 DHS show a decline in vaccination coverage from 45% in 2013–2014 to 21% in 2023–2024, with zero-dose children increasing from 6% to 23%. This national crisis situates Lomami’s challenges within broader systemic weaknesses, requiring interventions such as strengthening cold-chain logistics, improving data quality, and integrating vaccination with maternal and child health services.13–16,19

Children from very low-income households were consistently at higher risk of non-vaccination, reflecting financial and structural barriers. Divorced mothers were also more likely to have unvaccinated children, though wide confidence intervals suggest instability in these estimates. Further qualitative research is needed to understand how family dynamics influence vaccination decisions.

Low maternal education was associated with non-vaccination, consistent with evidence that education improves awareness and trust in health services. However, given that 43% of respondents did not report education, this association must be interpreted cautiously.

Structural challenges—including vaccine stockouts, remoteness of health centers, and unsuitable schedules—were frequently cited. Cultural beliefs and rumors about side effects also contributed to mistrust.11–15 Because these variables were measured in a limited way, findings related to beliefs should be considered exploratory rather than definitive.

Similar patterns are observed elsewhere: in Ethiopia (GAVI, 2021), 9.8% of children were unvaccinated due to economic and educational barriers; in the Central African Republic,17 11% were affected by political and logistical causes; and in Haiti,18 14% were influenced by widespread distrust. The DRC 2024 DHS further confirms declining national coverage, with zero-dose children rising sharply. This crisis increases the risk of preventable diseases and underscores the urgency of strengthening supply, awareness, and equitable access.13,14

Strengths and limitations

This study benefits from a large sample size (1,580 children), enhancing representativeness and statistical robustness. The diversity of maternal and socioeconomic profiles enriches analysis, and the use of recent data allows comparison with national and international trends.

However, several limitations must be emphasized. First, the cross-sectional design prevents causal inference, so associations should be interpreted as correlational. Second, vaccination status relied partly on self-reported data when cards were unavailable, introducing recall bias. Third, missing data—particularly maternal education—may have distorted regression estimates. Fourth, some regression results showed implausibly wide confidence intervals, reflecting model instability due to sparse data. Finally, as a secondary analysis, the dataset lacked potentially important variables such as distance to health facilities, household income, or exposure to vaccination campaigns. These limitations highlight the need for cautious interpretation and for future studies using longitudinal and mixed-method approaches.

CONCLUSIONS

This study identified a 10% non-vaccination rate among children aged 12–23 months in Lomami province in 2023, driven by structural and social barriers. Vaccine shortages, remoteness of health facilities, and limited maternal awareness emerged as key obstacles. Economic vulnerability and low educational attainment further exacerbate inequities in access to preventive care. Addressing these challenges requires targeted strategies to strengthen supply chains, improve service accessibility, and enhance caregiver knowledge. A community-based, multisectoral approach is essential to achieve equitable and sustainable vaccination coverage.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the commitment of the Kinshasa School of Public Health (KSPH) for providing access to the data, as well as the invaluable support of survey supervisors and community leaders during data collection.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Ministry of Public Health of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval for the 2023 vaccination coverage survey was obtained from the National Health Ethics Committee of the Democratic Republic of Congo (Approval No. NHREC/2023/045). Written informed consent was obtained from all participating mothers and caregivers.

Data availability

The dataset analyzed in this study was extracted from the national vaccination coverage survey database. Access to anonymized data can be requested from the Ministry of Public Health, Democratic Republic of Congo.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The article publication charge (APC) was funded by the authors.

Authorship contributions

-

Kadima Musasa Hakim: Conceptualization, methodology, data analysis, drafting of manuscript.

-

Nkongolo Bernard-Kennedy: data analysis, critical review, and editing.

-

Mukuna Muya Donat-Soft: Data interpretation, literature review, manuscript revision.

-

Kadima Musasa Derick: Statistical analysis, results validation.

-

Nyandwe Kyloka Jean: Field coordination, data quality assurance, manuscript editing.

Disclosure of interest

The authors completed the ICMJE Disclosure of Interest Form (available upon request from the corresponding author) and disclose no relevant interests.