Diabetes is a chronic disease that poses major challenges for children and their families worldwide, including in high-income countries.1,2 Pediatric management requires a tailored approach distinct from adults, involving multidisciplinary teams trained to prevent complications and provide psychosocial support.3,4 In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), several urban centers have benefited from training programs to strengthen pediatric diabetes care, but Sankuru province, particularly the Katako-Kombe health zone, remains underserved.5–9

Globally, the burden of diabetes among young people continues to rise. In 2022, an estimated 8.75 million individuals were living with type 1 diabetes, including 1.9 million in low- and lower-middle-income countries. Of these, 1.52 million were under 20 years of age, and diabetes accounted for 182,000 deaths worldwide, with 42,000 in Southeast Asia and 38,000 in Africa.10–14 In Africa, diagnosis is often delayed, with inaugural diabetic coma occurring in nearly one-quarter of cases. Misdiagnosis, combined with limited access to insulin, syringes, and monitoring devices, contributes to high pediatric mortality.8,12–17

Despite these challenges, pioneering efforts have emerged in the DRC. In 2001, Dr. Declerck initiated a program in Kinshasa, later integrated into Novo Nordisk’s “Changing Diabetes in Children” (CDiC) project in 2010, which established four specialized clinics and provided free care for more than 400 young patients. Yet, Sankuru province has no structured program for pediatric diabetes management.18–22

The 2022 Katako-Kombe report highlights systemic barriers: 40% of patients first consult traditional practitioners, 10% self-medicate, and no prior study has documented pediatric diabetes care in this health zone. The absence of staff training, awareness campaigns, and resources underscores the urgency of targeted interventions. This study therefore aims to describe the management of diabetes in children aged 0–18 years in Katako-Kombe, providing the first documented evidence from this rural and under-researched context.

METHODS

TYPE OF STUDY

This study was designed as a retrospective case series. It describes and analyzes 32 pediatric diabetes cases identified between July 1 and 31, 2024, in health care facilities (HCFs) of the Katako-Kombe health zone (HZ). The study does not estimate population prevalence but reports facility-based cases, acknowledging that findings cannot be generalized to the wider population.

STUDY SITE

The Katako-Kombe rural health zone, located in Sankuru province, covers 8,400 km² with 176,349 inhabitants across 258 villages. The area is geographically isolated and difficult to access, particularly during the rainy season. The population relies mainly on subsistence farming (cassava, corn, peanuts), artisanal fishing, and livestock. The healthcare system is fragile, with under-equipped facilities, shortages of staff and medication, and limited external support. While Memisa Belgium provides maternal health and family planning assistance, no partner supports diabetes care, leaving children with chronic conditions particularly vulnerable.

STUDY POPULATION

The study population consisted of:

-

Medical records of children aged 0–18 years diagnosed with diabetes and followed in specialized structures of the Katako-Kombe HZ.

-

Healthcare providers involved in pediatric diabetes management.

SAMPLING

STATISTICAL UNITS

-

Healthcare providers assigned to diabetes care services.

-

Medical records of children aged 0–18 years with diabetes.

SAMPLE SIZE

The study included 32 medical records of diabetic children and 55 healthcare providers. The small sample size is acknowledged as a limitation, restricting representativeness and statistical power. Findings should be interpreted as descriptive of observed cases rather than generalizable estimates.

SAMPLING TECHNIQUE

Exhaustive inclusion was applied to all available cases. Of 17 health areas, 13 reported diabetes management activities. All 38 HCFs in these areas were visited, but only 13 provided diabetes care. This selective inclusion introduces potential selection bias, as facilities without diabetes services may have excluded undiagnosed or unmanaged cases.

For healthcare providers, purposive sampling was used. In each of the 12 ESS, four providers were recruited (a full-time nurse, a community relay, a nurse in the care department, and a laboratory technician). At the General Reference Hospital (HGR), seven professionals were included (medical director, head of staff, director of nursing, heads of internal medicine, pediatrics, and laboratory, plus a community relay). This ensured coverage of key roles but did not guarantee proportional representation.

DATA COLLECTION

Authorization was obtained from the ESP/UNIKIN Ethics Committee and local authorities. Data collection involved:

-

Documentary review of medical records of diabetic children. Completeness and consistency were assessed; missing or inconsistent data were noted and excluded.

-

Structured interviews with providers, using a digital questionnaire administered via ODK. The questionnaire was pre-tested in a non-study facility. Reliability was strengthened through interviewer training, but no formal validation or triangulation was performed, which is acknowledged as a limitation.

-

Interviews were conducted in French or Kitetela, depending on participant preference.

DATA PROCESSING AND ANALYSIS

Data collected via ODK were exported to Excel and analyzed in SPSS 25.

-

Categorical variables were summarized in absolute and relative frequencies.

-

Age was grouped into two categories (0–14 and 15–18 years) to distinguish children from adolescents. This classification was pragmatic but acknowledged as arbitrary.

-

Only descriptive statistics were applied. Inferential analyses (e.g., chi-square, logistic regression) were not performed due to the small sample size, limiting analytical depth.

ETHICS CONSIDERATIONS

This study received approval from the ESP/UNIKIN Ethics Committee (ESP/CE/155/2024). Investigators were trained in respect, confidentiality, and informed consent. For minors, informed consent was obtained directly from parents or legal guardians after providing clear information about study objectives, procedures, risks, and benefits. Consent forms were translated into the local language, and investigators verified comprehension before signatures were collected. Authorization was also obtained from ESS managers to access facility records. Consent procedures for reviewing medical records were explicitly explained to parents or guardians, ensuring voluntary participation without impact on care.

Data were anonymized and stored securely on a password-protected computer accessible only to the principal investigator. No adverse events or sensitive cases were reported during interviews. Equitable inclusion was ensured, with all eligible cases included regardless of sex, age, or socioeconomic background

RESULTS

DISTRIBUTION OF PEDIATRIC DIABETES CASES

Figure 1 shows the distribution of diabetes cases across the 13 health care facilities (HCFs) included in the study. A total of 32 children were identified with diabetes during July 2024. This represents 6.7% of the 478 children aged 0–18 years who attended these facilities for various conditions. This proportion reflects a facility-based frequency, not a population prevalence, and should be interpreted with caution.

SOCIODEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS

Table 1 summarizes the sociodemographic profile of the 32 children. The mean age was 10.9 ± 4.2 years, with nearly 80% under 14 years. Boys were more represented (sex ratio 1.5). One-quarter had no schooling, while 75% were enrolled in school. Most children (75%) lived in households with more than five members. More than a quarter were followed at the General Reference Hospital (HGR), and 60% attended scheduled medical appointments. These findings are descriptive and do not establish causal relationships between sociodemographic factors and disease management.

FAMILY AND LIFESTYLE CHARACTERISTICS

Table 2 presents family and lifestyle data. Nearly 60% of children did not know their family history of diabetes, while 70% had both parents alive. Sixty percent adhered to regular check-ups. More than 80% reported no alcohol or tobacco use, and nearly 70% had heard of diabetes in young people. These findings reflect reported contexts but do not demonstrate associations with outcomes.

CHARACTERISTICS OF HEALTH FACILITIES

Table 3 outlines the characteristics of the health structures. Diabetes care and screening were available in all included facilities. However, infrastructure gaps were noted, including absence or inadequacy of consultation rooms, therapeutic education spaces, toilets, showers, and pharmaceutical depots. The assessment was limited to availability; functionality and adequacy could not be systematically evaluated.

HUMAN, MATERIAL, AND FINANCIAL RESOURCES

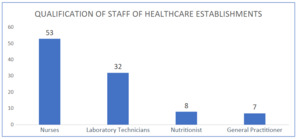

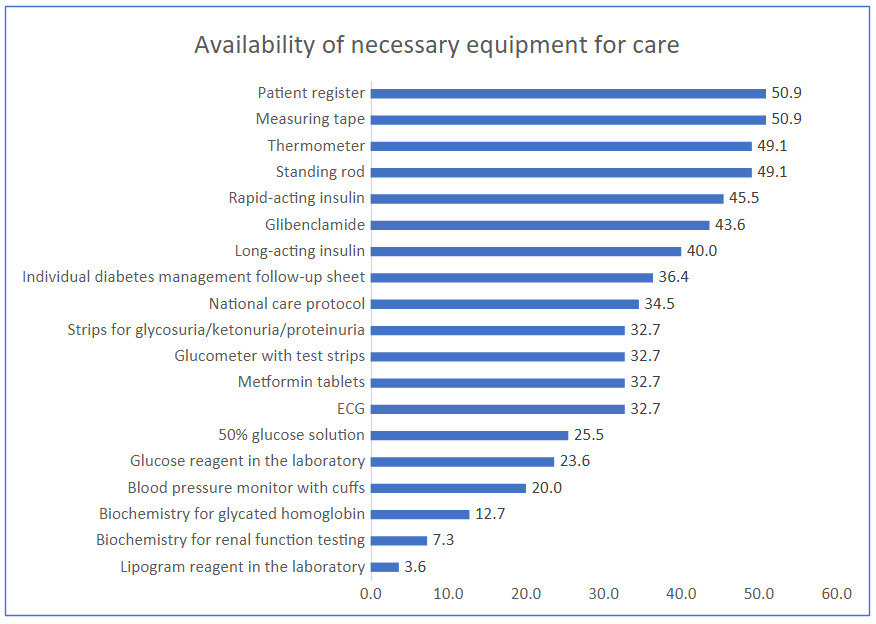

Figure 2 shows that more than half of professionals involved in pediatric diabetes care were nurses and laboratory technicians. Figure 3 indicates that tape measures (50.9%) and patient registers (50.9%) were the most available items. Glucometers with strips were available in 32.7% of facilities. Rapid insulin was accessible in 45.5% of facilities, and delayed-release insulin in 40.0%.

PROPOSED ACTIVITIES

All ESSs provided consultations and blood sugar testing. Complementary services were limited: medication management was available in only two ESSs, nutritional care in one, and complication management in one. No facility offered psychological support, hygiene promotion, therapeutic education, or physical activity programs.

Overall, these results highlight service availability but do not assess quality or outcomes. The absence of psychosocial and nutritional services is a descriptive finding; its impact on adherence or complications was not measured in this study.

DISCUSSION

KEY RESULTS

This study provides the first descriptive account of pediatric diabetes management in the Katako-Kombe Health Zone. Thirty-two children aged 0–18 years were identified across 13 facilities, representing 6.7% of children attending these facilities for various conditions during July 2024. Most were under 14 years, boys were slightly more represented, and one-quarter had no formal education. Household overcrowding was common, and many children lacked knowledge of family history. While 60% adhered to medical appointments, infrastructure and resources remained limited, with glucometers available in only one-third of facilities and insulin inconsistently supplied. Psychosocial and nutritional services were largely absent.

These findings highlight systemic gaps in pediatric diabetes care. However, they must be interpreted cautiously: the reported frequency is facility-based and does not represent population prevalence. The descriptive nature of the data limits causal inference, and observed associations (e.g., between education and disease management) cannot be confirmed.

The facility-based frequency of 6.7% reflects the proportion of children with diabetes among those attending care during the study period, not the true prevalence in the community. Direct comparisons with population-based studies in other African countries are therefore limited. For example, Majaliwa et al.23 reported population-based rates ranging from 0.3 per 1,000 in Nigeria to 10 per 100,000 in Sudan, while Butembo (DRC, 2024) reported 1.33% among children under 15 years. These figures are not directly comparable to facility-based data.

Globally, pediatric diabetes continues to rise. The IDF24,25 estimates 3.4 million children living with type 1 diabetes in 2025, with incidence increasing by 1.4% annually between 1990 and 201926–29). Studies such as TEDDY27 and Ziegler et al.30–32 highlight the role of genetic predisposition, viral infections, and nutritional factors. In Africa, where 72.6% of diabetes cases remain undiagnosed,26 limited access to care exacerbates risks of severe complications. In this context, the Katako-Kombe findings underscore the importance of strengthening early detection and ensuring access to treatment, while recognizing the limitations of facility-based data.

The study revealed significant disparities in human and material resources. Most providers were nurses and laboratory technicians, with few specialized staff. Consultation areas were rare, and essential supplies such as insulin were inconsistently available. While tables documented availability of equipment, functionality and adequacy could not be systematically assessed, which limits interpretation.

These findings align with Lubaki et al.29 in the DRC and Ogurtsova et al.30 in sub-Saharan Africa, who emphasize under-equipment and lack of trained personnel as major barriers to timely diagnosis. Globally, resource disparities mirror socio-demographic indices: countries with higher indices benefit from better infrastructure,23 while low- and middle-income countries face rising incidence but limited resources.26 In Katako-Kombe, the absence of adequate infrastructure and specialized staff plausibly contributes to delayed diagnosis and poor follow-up, though this study did not quantify such outcomes.

Care activities were limited to consultations and blood glucose testing. Few facilities offered medication management, nutritional care, or complication management, and none provided psychosocial support or therapeutic education. These gaps are descriptive findings; their impact on adherence or complications was not measured in this study.

Lubaki et al.29 noted similar coordination challenges in the DRC, while Ogurtsova et al.30 estimated that 72.6% of cases in sub-Saharan Africa remain undiagnosed due to lack of training and equipment. Kan et al24 highlighted global increases in childhood diabetes linked to obesity, dietary changes, and inadequate provider training. In Katako-Kombe, the absence of integrated services reflects fragmented care and likely contributes to poor disease management, though quantitative associations were not established.33–36

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

This study provides a comprehensive overview of pediatric diabetes care across all facilities offering such services in Katako-Kombe, highlighting systemic inadequacies in human, material, and financial resources; however, several limitations must be acknowledged, including the facility-based design whereby the reported 6.7% frequency reflects children attending care during one month and cannot be generalized to the population, variability in the completeness of medical records with potential bias from missing data, infrastructure assessment limited to availability without systematic evaluation of functionality or adequacy, uncertainty regarding whether parental consent was consistently secured for each child’s record despite facility approval, the absence of reported adverse events or sensitive cases during interviews which may reflect underreporting, and an analytical scope restricted to descriptive statistics without inferential analysis due to the small sample size; future research should therefore adopt longitudinal designs, incorporate standardized diagnostic criteria, and explore associations between resource availability, adherence, and clinical outcomes to strengthen evidence and guide interventions

CONCLUSIONS

This study provides the first descriptive case series of pediatric diabetes management in Katako-Kombe, highlighting serious gaps in care due to limited human, material, and financial resources. Infrastructure was inadequate, insulin and glucometers inconsistently available, and psychosocial or nutritional support services absent. The reported 6.7% frequency reflects facility-based cases during one month and cannot be generalized to the wider population. Findings underscore the urgent need for staff training, improved supply chains, and integration of multidisciplinary services adapted to the local context, with closer collaboration between health professionals, families, and schools. Future research should evaluate rural care models, explore social determinants of adherence, assess long-term impacts of integrated approaches.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to all participants, healthcare providers, and data collectors who contributed to this study.

DISCLAIMER

The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the institutions involved.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Public Health, University of Kinshasa (Approval No. ESP/CE/155/2024). Informed consent was obtained verbally from all participants prior to data collection. Confidentiality and anonymity were strictly maintained throughout the study.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

FUNDING

The research presented in this manuscript received no external funding. The authors confirm that no article publication charges (APC) were funded by external sources.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTIONS

-

Michel Omanyondo: Conceptualization, data collection, drafting of the manuscript.

-

Bernard-Kennedy Nkongolo: Methodology, data analysis, critical revision of the manuscript.

-

Marie-Claire Muyer Muel Telo: Supervision, validation, final approval of the manuscript. All authors meet the ICMJE authorship criteria, contributed significantly to the work, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

DISCLOSURE OF INTEREST

The authors completed the ICMJE Disclosure of Interest Form and disclose no relevant interests.