In the global pursuit of mitigating the burden of preventable blindness, the creation of a peer-reviewed, open-access paper outlining established optometric training programs worldwide as of 2023 is critical. The prevalence of vision impairment and blindness persists as a significant public health challenge, particularly in vulnerable communities and developing nations where access to eye care services is limited. By compiling a comprehensive chart of optometric training programs, this initiative enables non-profits, policymakers, and other stakeholders to assess which countries or regions are in critical need of additional eye care professionals and new training initiatives. By mapping the training institutions and number of independent eye care providers worldwide, this paper facilitates targeted interventions to address gaps in healthcare infrastructure and bolster human resources in regions where preventable blindness remains a pressing issue. Moreover, it highlights potential shortcomings in pharmaceutical reliability, infrastructure, and other systemic factors within developing nations, galvanizing strategies that aim to enhance the access of underserved populations to quality eye care worldwide.

Mapping the full extent of optometric educational institutions and levels of care has been attempted multiple times in the past.1,2 Other articles have focused on mapping disparities between countries that have poor access to eye care providers. This article is unique in its multifaceted approach by providing a comprehensive list of optometric training programs, updating estimates of eye care providers, and sharing the level of care provided by optometry in relation to the country’s population. Our research aims to contribute as an additional data point for comprehensive eye care assessment. Multiple, repeated studies are needed to gain a comprehensive understanding of the global need for eye care providers. Moreover, relying solely on a single study may introduce limitations and errors. This article will be freely accessible, in contrast to others that require payment, potentially limiting their visibility and impact, as evidenced by their low citation count. To the best of my knowledge, no other publication systematically charts every existing optometry training program and juxtaposes them with the current standards set by the World Council of Optometry.

Although documentation of numbers of eye care providers, population sizes, and scope of practice may be beneficial in gathering a basic understanding of a country’s eye care burden, a true comprehensive picture of available eye care includes other drivers and correlates. Factors like age distribution and urban-rural divide are social factors that provide a more detailed understanding of patient demographics. Moreover, infrastructural factors like access to technology and physical clinic space are limiting factors to eye care services. Economic factors like GDP, health expenditure costs, income distribution, and insurance coverage further shape the accessibility and quality of eye care. Other societal distinctions such as educational levels and public awareness play a vital role in the utilization and delivery of eye care services.

Ophthalmic Professions

Many countries rely on a diverse array of professionals, including ophthalmologists, optometrists, ophthalmic nurses, ophthalmic technicians, and opticians to deliver comprehensive eye care. Understanding the roles and required training of these various providers offers insight into the dynamics of global eye care systems. Because optometry is neither recognized as a profession worldwide, nor does it follow universal standards of training, this paper aims at providing transparency and introducing the field of optometry as a career path to help with the lack of eye care providers worldwide. This paper highlights regions worldwide that may benefit from additional eye care providers who are able to perform refractive care along with varying degrees of advanced, independent medical management of ocular pathologies. In short, our goal is to publish a document that fosters uniformity in optometry care and enables efficient management of ocular diseases for providers at all training levels.

In the United States, ophthalmologists are medical doctors who complete medical school prior to specializing in eye care. They are comprehensive ophthalmic surgeons and may choose to further subspecialize in certain areas of eye care including pediatrics, glaucoma, oculoplastic surgery, neuro-ophthalmology, ocular immunology, cornea, retina, and ocular oncology. Because of their completion of medical school, ophthalmologists can prescribe any medication for the body if they elect to do so. However, most choose to collaborate with other medical personnel to manage non-ophthalmic conditions.

Historically, optometrists were refractive spectacle providers with roots in opticianry and jewelry.3 Over the centuries, the profession of optometry has changed, shifting into primary medical care to assess refractive error and determine causation of decreased acuity. From there, optometry advanced into treatment and management of ophthalmic conditions, creating specializations through residency and fellowship training in the areas of primary eye care, ocular disease, specialty contact lenses, binocular vision, pediatrics, and low vision.4

Because of the inconsistencies in optometric training worldwide, optometric skillsets vary from country to country. In the United States and Canada, optometrists complete undergraduate training in pre-medical sciences (3-4 years), and most hold an undergraduate degree.5 Some programs matriculate students without an undergraduate degree if the student shows exceptional aptitude in their application. Before applying to American optometry schools, students must take the Optometry Assessment Test, which is a comprehensive examination covering all undergraduate premedical coursework. Pending satisfactory test scores, the students matriculate into optometry school, where they complete four additional years of optometric education specifically focused on the eye and visual system. This differs from medical school in that optometry school does not require hospital rotations or electives in non-ophthalmic training. After completing their four years of optometry school, students must pass three national board examinations, covering the four years of training they have acquired including basic science, pathophysiology, pharmacology, and ophthalmic procedures. Consequently, optometrists in the United States hold a doctorate-level education and are only able to prescribe and treat patients for ophthalmic related conditions. They also have limited surgical and procedural scope of practice. Optometry works in cooperation with ophthalmology to provide surgical subspecialty patient referrals and more complex conditions to specialists, similarly to other medical surgical and non-surgical specialties.

Optometrists in other countries may be trained in comprehensive evaluation of the eye and visual system. This includes medical evaluation of the visual system alongside performing refractive care, providing glasses, contact lenses, ocular alignment assessments, and low vision devices. In some countries, optometrists are limited just to refractive care. As the profession of optometry evolves, education and training continue to develop, allowing for more independence and patient management. In some countries offering multiple optometric degree certifications, additional education grants the provider a broader scope of practice within the country.

Ophthalmic nurses can vary in training from country to country. They may hold a general nursing degree but work in the ophthalmology surgical space to help during surgeries, and throughout pre-operative and post-operative care. These ophthalmic nurses may have overlap with ophthalmic technician training.6

Ophthalmic technicians/assistants are trained to gather baseline ophthalmic data including collecting detailed case histories, assessing visual acuities, measuring intraocular pressure, performing ophthalmic testing, and telephone triaging urgent vs non-urgent cases. In some countries, ophthalmic technicians act as community liaisons, providing basic refractive care and creating referrals to independent eye care providers depending on their triage training.7

Opticians are primarily trained to make glasses, and in many countries, to provide refractive care like glasses and contact lens prescriptions to patients like technicians, optometrists, and ophthalmologists.8

The combination of each of these professionals provides access to eye care worldwide. Each plays a critical role in treating and preventing blindness by complementing the others’ skill sets and helping offset burden based on each occupation’s training.

This study addresses the following research questions: 1) How many optometric training programs exist worldwide? 2) Which regions have shortages of eye care providers and how can these gaps be identified through mapping training optometric programs? 3) What is the scope of practice for optometrists in each country? 4) How can establishing local optometric training programs in underserved regions help reduce preventable blindness, increase access to primary eye care, and improve quality of life?

METHODS

This study follows the key principles of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) framework to provide a structured methodology, transparency, and reproducibility of the data on optometric training programs and scopes of practice globally along with numbers of practicing optometrists and ophthalmologists.9

WorldBank data was used to determine the population of each country as of 2022. To compile data on optometric training programs worldwide as of 2023, a systematic approach was employed.10 Google searches were conducted using specific keywords such as “optometry program worldwide,” “optometry training worldwide,” “optometry school worldwide,” and “optometry degree,” paired with the name of each country under consideration. This search strategy aimed to verify the existence of optometric training programs within each country. Data sourced from these searches were either available in English or translated into English for analysis. In cases where no institution was found, members of the group contacted professional optometric associations, community optometrists, or national health departments via email to inquire about the training programs. Programs were included if they had publicly available data or communicated by professional associations. Programs were excluded if no reliable online or institutional sources were found. All data were independently verified by at least two authors. Discrepancies were resolved through group discussion and if needed, follow-up correspondence with local optometrists or professional associates were made.

Scope of practice data was sourced through Google searches using specific keywords such as “optometry law,” “optometry scope,” or “optometry bylaw,” paired with the name of each country under consideration. This search strategy aimed to verify the scope of care provided by optometrists in each country. Data sourced from these searches were either available in English or translated into English for analysis. In cases where no institution was found, members of the group contacted professional optometric associations, community optometrists, or national health departments via email to inquire about the scope of practice that optometrists performed in the country.

Additionally, the International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness (IAPB) atlas was utilized to ascertain the number of practicing optometrists and ophthalmologists in each region.11 This information provided valuable insights into the current workforce composition and distribution of eye care professionals across different countries.

The scope of practice adheres to the standards outlined by the World Council of Optometry Global Competency-Based Model of Scope of Practice in Optometry.12 This model serves as a universal benchmark to help states and nations worldwide streamline differences in optometric practice scopes on an international scale.

The four categories for scope of practice include the following:

-

Optical Technology Service (I) - Management and dispensing of ophthalmic lenses, ophthalmic frames and other ophthalmic devices that correct defects of the visual system.

-

Visual Function Service (II) - Optical Technology Services plus Investigation, examination, measurement, recognition, and correction/management of defects of the visual system (note: practitioners at Level 2 are considered optometrists).

-

Ocular Diagnostic Service (III) - Optical Technology Services plus Visual Function Services plus Investigation, examination and evaluation of the eye and adnexa, and associated systemic factors, to detect, diagnose and manage disease

-

Ocular Therapeutic Service (IV) - Optical Technology Services plus Visual Function Services plus Ocular Diagnostic Services plus use of pharmaceutical agents and other procedures to manage ocular conditions/disease.

RESULTS

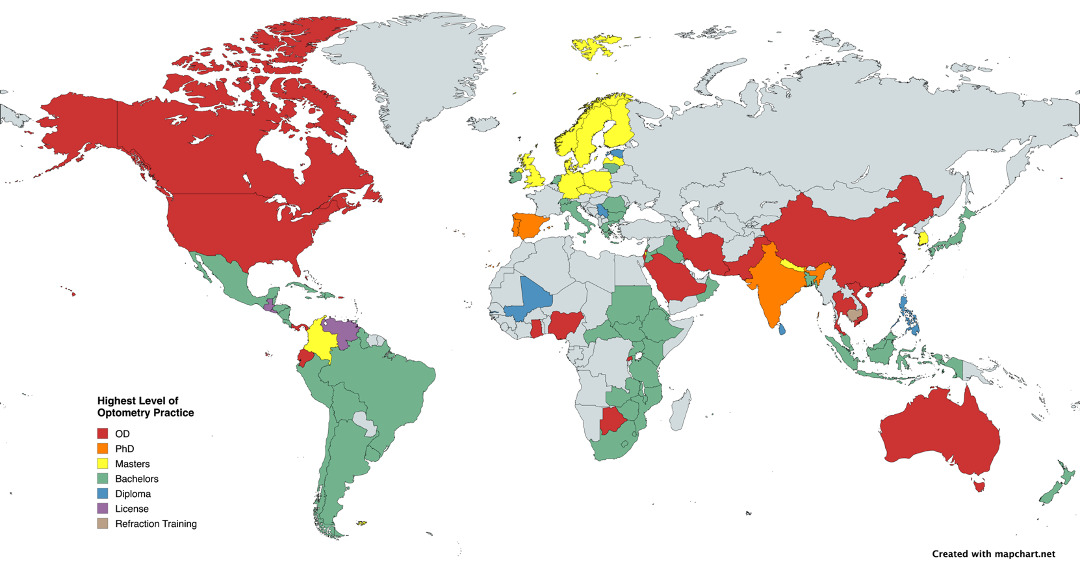

The total numbers of countries and territories analyzed was 224. Out of the 224 countries and territories evaluated, 96 had optometric training programs (42.86%). Herein, “countries” will refer to both nations and individual territories. North America housed 13 out of the 96 countries with optometric training programs or 13.54%. South America housed 10 of the 96 countries with optometric training programs or 10.42%. Europe housed 26 of the 96 countries with optometric training programs or 27.08%. Africa housed 20 of the 96 countries with optometric training programs or 20.83%. Asia and the Middle East had 25 out of the 96 countries with optometric training programs or 26.04%. Australia and Oceania had 2 out of the 96 countries with optometric training programs or 2.08% (Figure 1).

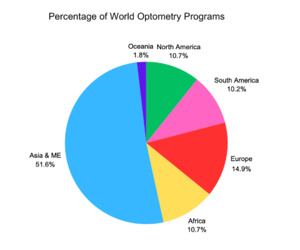

The total number of optometric training programs currently in existence is approximately 382. North America houses 41 of the 382 total optometric training programs (10.73%). South America houses approximately 39 total optometric training programs (10.21%). Europe houses approximately 57 total optometric training programs (14.92%). Africa houses approximately 41 total optometric training programs (10.73%). Asia and the Middle East house approximately 197 optometric training programs (51.57%). Oceania and Australia house 7 optometric training programs (1.83%) (Figure 2). Detailed data of specific programs of each continent are presented in the Online Supplementary Document.

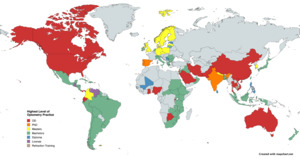

Breakdown of degree type per institution:

- 7 countries housed institutions where optometry education is at a license level.

(Note: some licenses are also Bachelor’s degrees) - 12 countries housed institutions where optometry education is at a diploma level.

- 72 countries housed institutions where optometry education is at a Bachelor’s level.

- 24 countries housed institutions where optometry education is at a Master’s level.

- 15 countries housed institutions where optometry education is at a doctorate level (OD or PhD) (Figure 3).

Asia houses 61.65% of the global population. Africa houses 18.68% of the global population. Europe houses 9.26% of the global population. North America houses 7.6% of the global population. South America houses 5.53% of the global population. Oceania houses 0.58% of the global population. Given this population distribution, we would expect a higher number of optometric training programs in Africa and Asia to meet the vision care needs. Broad continental generalizations, however, may not adequately address specific areas with rural regions and limited access to care such as the Caribbean or Sub-Saharan Africa.

DISCUSSION

Mapping the number of optometry training programs alongside the number of optometrists and ophthalmologists worldwide offers numerous benefits. First, it provides valuable insights into the distribution of eye care providers, thus helping identify regions with shortages and prompting healthcare interventions to reduce eye health disparities and foster health equity. This data supports countries, nonprofit organizations, and aid programs in making informed decisions for future policy making and disease prevention efforts. Additionally, future training institutions can utilize this information to determine where to establish new programs or outreach initiatives, addressing gaps in the availability of eye care professionals. Furthermore, mapping optometrists along with their education and scope of practice specifically helps highlight inconsistencies in standards of care and education, therefore guiding improvements in the quality of eye care services globally.

Research has shown that the prevalence of vision impairment and blindness has remained higher in regions with limited optometric training and lower in areas such as North America and Oceania over the past few decades.13,14 This disparity is influenced by structural barriers within health systems such as uneven distribution of trained personnel and limited funding for eye care services. Financial constraints in underserved regions can further prevent access to quality eye care. Moreover, comparing our findings with Flaxman et al. and the Vision Loss Expert Group data suggests that regions at higher risk of vision impairment are also those with fewer optometry programs or restricted scopes of practice for optometrists.13,14 Although more research is needed to establish causal relationships, these correlations suggest investing in optometric education can strengthen primary eye care delivery, expand scope of practice, and promote early detection and correction of refractive errors and ocular diseases.

Optometry has evolved over the course of centuries to become the cornerstone of eye care and developed to bridge the gap between screening systems and advanced surgical care. To do so, proper training is essential. For example, with additional training, an optometrists’ ability to assess the presence and severity of diabetic retinopathy in individuals with diabetes improved significantly - more dilated eye exams were performed (from 79.5 to 84.4%), rate of improper follow-up instructions decreased (from 13.8 to 10.8%), and documentation of diabetic retinopathy-related findings, assessment and plan, and billing and coding improved significantly (from 78.8 to 88.7%).15 Additionally, in the United States, for example, independent management of ophthalmic diseases by doctors of optometry has led to an average of 12% decrease in vision impairment nationally.16 As specialized eye care practitioners, optometrists can provide a more effective vision screening compared to primary care practitioners especially in regard to asymptomatic individuals with community-based screenings proven effective in high-risk, underserved areas.17

While short term solutions like deploying mobile training units or forming partnerships with non-profit organizations or foreign institutions can provide immediate relief, the sustainability of such interventions depends on fostering local expertise and infrastructure. Establishing local optometric training programs and elevating the educational expectations of existing optometric training programs holds great promise for the future of accessible eye care, particularly those in marginalized communities who already face economic, educational, and social challenges. By training healthcare professionals domestically, underserved populations can expect enhanced accessibility to healthcare services, resulting in notable improvements in their overall wellbeing and healthcare outcome.

Several initiatives have been considered to address the gaps in eye care worldwide. Primary care providers ranging from nurse practitioners to primary care physicians have been utilized to implement vision screenings through visual acuity testing, fundus imaging, and direct ophthalmoscopy.18,19 Additionally, community health workers and trained para-ophthalmic staff, including ophthalmic nurses and technicians, have been employed to conduct routine eye screenings at various levels to refer patients who have ocular pathologies.20 Artificial intelligence has emerged as an innovative method to provide access to ophthalmic evaluations using recognition software or remote ophthalmic providers.21

Strength and Limitations

Strengths

-

This paper compiles a detailed global map of optometric training programs, outlining their prevalence, distribution, and varying educational standards. This data is essential for identifying areas with shortages in eye care professionals.

-

By highlighting gaps in eye care availability, particularly in vulnerable and underserved regions, the paper underscores the urgency of addressing preventable blindness, a critical public health issue.

-

The use of reputable data sources including the World Bank and the International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness as well many peer-reviewed journal perspectives and evaluations.

-

By examining the inconsistencies in optometric education and scope of practice globally, this paper identified opportunities for standardization and improvement, which could elevate the quality of eye care worldwide.

-

This paper takes a multifaceted approach, integrating data on training programs, scope of practice, and global population needs. It serves as a critical resource for both understanding and addressing disparities in eye care.

Limitations

There were several factors that played into data gathering for this mapping.

-

Not all programs are documented on websites or updated with current enrollment or accredited institutions. This was especially true for low- and middle-income countries. Additionally, many countries did not have the profession of optometry. Additionally, optometry was often used interchangeably with responsibilities of opticians.

-

Many countries had various levels of optometric training including, but not limited to diploma, bachelor’s degree, master’s degree, and doctorate-level training. As such, countries that offered dynamic scope of practice changes based on education levels were incorporated. In some countries, additional education beyond diploma or bachelor’s degree did not affect scope of practice eligibility.

-

Not all programs were documented in English nor had their scope of practice management easily available online. As such, the group contacted several health director personnel, universities, or optometric organizations within each country to inquire about what optometrists were trained to manage independently within each country’s legal confines.

-

Not all countries had demographic data of population size, number of optometrists, or number of ophthalmologists. This may be due to civil conflict within the country, poor response rate from IAPB surveys, or poor recordkeeping.

-

Optometry in many countries is an unregulated profession. As such, scope of practice and quality of clinical examinations vary from provider to provider. This was often further exacerbated by lack of medicine regulation standards.

-

Some countries receive eye care services from providers based in their governing nations. For instance, the United States and Great Britain had programs where eye care providers are sent to their satellite island territories to provide remote medical care.

CONCLUSIONS

Optometry is a relatively new profession that varies in definition and scope of practice from country to country. Training in optometry can range from opticianry, refraction, orthoptics, vision rehabilitation, and contact lenses to fundoscopy, ophthalmoscopy, and independent management of ocular pathologies. Lack of global standardization in curricula, degree type, and years of training make understanding of optometric education challenging. Furthermore, poor online transparency in documentation of curricula, scope of practice, and educational institutions further exacerbate inconsistencies in the profession.

These regional inconsistencies in optometric education and concentration may contribute to poor health literacy and healthcare disparities. Although countries like Pakistan and India house over 40 optometric training programs each, the level at which providers are trained varies based on degree obtained. While Asia and the Middle East host the most optometric training programs, the concentration of optometric providers is not evenly distributed among each of the countries in the region.

Low- and middle-income countries are areas where eye care is limited or non-existent. Regions particularly impacted by this disparity include sub-Saharan Africa, Central America, the Caribbean, and Oceania. Establishing optometric training programs in underserved areas across the globe has the potential to help reduce preventable blindness, improve quality of life, and create more efficient healthcare systems by generating in-country optometric providers.

A more in-depth analysis is needed to map the concentration of population demographics with the availability of eye care providers. In large countries, having several training programs does not necessarily correlate with adequate accessibility to care, as the locations of training programs and doctors may not align with where care is most needed.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Mariana P. Socal for her guidance on this project.

Funding

The research presented in the manuscript received no external funding.

Disclosure of interest

The authors completed the ICMJE Disclosure of Interest Form (available upon request from the corresponding author) and disclose no relevant interests.

Additional Material

This article contains additional information as an Online Supplementary Document.

Correspondence to:

Maythita Eiampikul

Massachusetts Eye and Ear (present)

243 Charles St, Boston MA 02115

United States of America

meiampikul@mgb.org