Experience and lessons learned from responding to public health emergencies such as Ebola Virus Disease (EVD), Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and other infectious disease outbreaks and natural disasters have stressed the vital role of national and subnational rapid response teams (RRTs) in the timely investigation and containment of such events.1,2 RRTs are multidisciplinary teams that include national health workers, trained and equipped, with the capacity to deploy rapidly to provide an efficient and effective response to health emergencies in coordination with other response efforts.3 In recent years, non-infectious disease global public health events including chemical, biologic, radiologic and nuclear incidents and natural disasters have also required a response by national health workers from both the human and animal health sectors, including RRTs, to intervene at the frontline as a crucial component of the global health emergency workforce (GHEW).4–6 The role of RRTs in global health incidents is therefore critical.

As part of its preparedness activities, and in response to the World Health Organization (WHO) Director-General report on the Sixty-eighth World Health Assembly (global health emergency workforce Report),7 WHO developed and implemented from 2015 to 2020 a variety of complementary learning initiatives meant to strengthen the capacities of national RRTs. Those included the development of online open access learning packages, training-of-trainers packages, and an online learning programme and webinar series focused on COVID-19 response.8 Throughout that five-year period, WHO country offices, regional offices and headquarters, conducted RRT trainings in over 65 countries in the African and Eastern Mediterranean regions (AFR and EMR) for RRT members, managers, and trainers involved in emergency response. In parallel, WHO has set up and managed a community of practice for previously trained members of RRTs (the RRT Knowledge Network).8

In 2021, the WHO’s Health Emergencies Programme, Learning Solutions and Training Unit (WHE-LST) conducted an evaluation to assess the impact of the formal WHO RRT capacity building activities conducted between 2015 and 2020. Key findings confirmed that participants had acquired valuable tools and resources to address challenges in the field and individuals had become more capable of dealing with crisis. RRT training also had a sustained impact on RRT team performance. However, this training was not guided by a clear and detailed competency framework specifically for RRTs that could be used to assess RRT skill gaps and to guide RRT learning in systematic way.

Thus, a key recommendation stemming from that evaluation was to develop an RRT competency framework that systematized all technical and managerial/administrative qualifications needed to successfully respond to public health events and emergencies, and then operationalize that framework to: 1) guide learning strategies for RRTs, keeping face-to-face training as a mainstay and using blended models whenever possible, and; 2) guide development of stronger training-of-trainers and performance management processes opportunities to encourage greater self-sufficiency in RRT activity at the country level.9

The WHO global competency and outcomes framework for universal health coverage defines competencies as “the abilities of a person to integrate knowledge, skills and attitudes in their performance of tasks in a given context”.10

Guided by the evidence-based RRT evaluation recommendations, we aimed to develop a competency framework for RRT managers, members, and trainers that was designed for this unique emergency response workforce. Specifically, we sought to identify and understand the professional competencies that RRT members, managers, and trainers currently receive training on and/or should receive training on, to become competent health emergency responders. This paper describes the methods and findings of the development process, as well as the resulting RRT competency framework. This framework aims to map and articulate the various competencies needed for early detection and rapid and effective response to public health events so that Member States can build capacity with each of the above actors and thereby strengthen their capacities in terms of preparedness, readiness, and response to public health emergencies.

METHODS

Study design

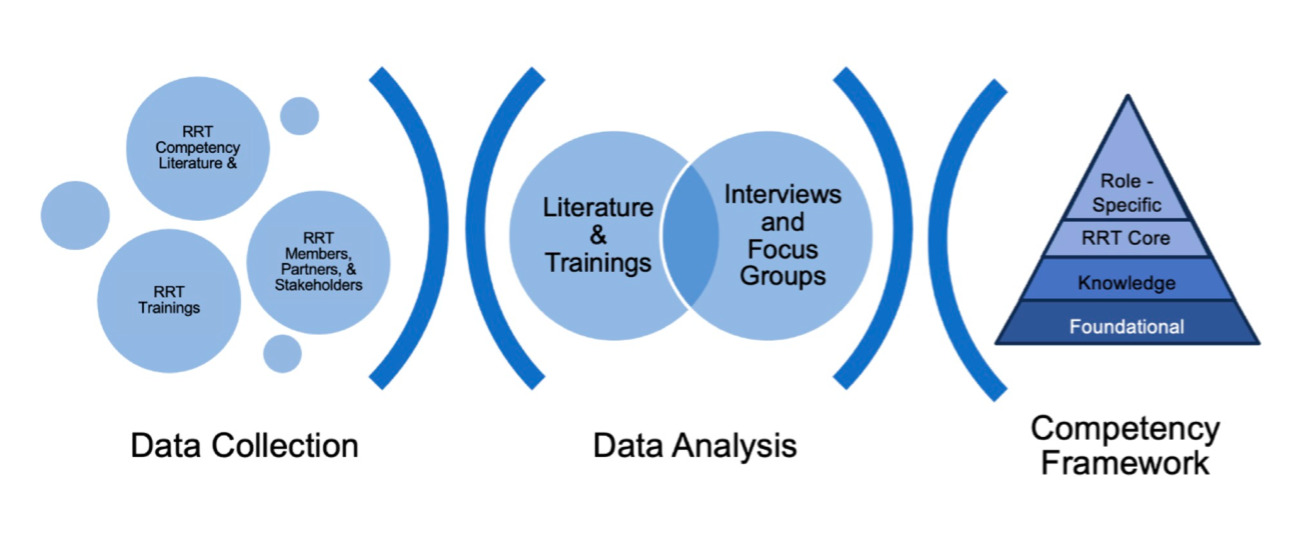

This qualitative study was conducted from June to December 2022 in two phases. The first phase consisted of a desk review of relevant RRT and emergency responders’ competency literature and existing RRT trainings. During phase 2 we conducted key informant interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs) with key RRT partners and stakeholders, to identify and understand RRT competencies, and how best to develop them. We analysed data from phase 1 and phase 2 to create a four-tiered competency framework for RRT members, managers, and trainers (Figure 1, Online Supplementary Document).

Phase 1: Desk review

The desk review began with foundational articles used by WHO LST authors in previous RRT trainings and guidance documents. Next, we searched the academic and grey literature using PubMed and Google Scholar with the following key search terms: “rapid response team,” “public health emergency response,” and “emergency workforce.” Last, we searched the reference lists of the resources from the WHO and articles identified from the academic and grey literature. Articles were included if they described the competencies required of RRTs and other emergency public health response personnel. We excluded articles that did not focus on this public health workforce sector or did not detail the competencies required.

The data extraction template included fields pertaining to emergency context, relevant stakeholder group, competency, competency definitions, and competency descriptions. Three reviewers extracted data from all included articles.

Phase 2: Qualitative study

We then conducted semi-structured, in-depth interviews (IDIs). The results of IDI analysis where then interrogated and refined through FGDs followed by member checking IDIs to increase the validity of the findings.11 This design involved systematic collection and thematic analysis of qualitative data. The interviewers and focus group facilitators had extensive training and experience in open-ended interviewing, group facilitation, and qualitative data analysis either from education or public health research contexts.

Sampling

We used a purposive sampling frame to recruit key informants who were trained and experienced with RRTs, situated in different levels of the response system, and from each of the six WHO regions for the first set of IDIs and for the FGDs. We identified and invited 12 individuals operating at the global level coming from the WHE-LST, Emergency Response Capacity team at the United States’ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US CDC), WHO Rapid Response Teams Working Group, or WHO Rapid Response Teams Knowledge Network. From each WHO region we identified and invited 1 regional level RRT trainer of trainers, 1 national level RRT emergency operations centre manager, 1 national level trainer, 1 national level trainee, and 1 subnational response team member; when these roles were filled within regions. We successfully recruited individuals from multiple levels of the system who represented four WHO regions - African Region, Eastern Mediterranean Region, South-east Asian Region, and European Region. Invited participants had experience with varied health emergencies i.e., disease outbreak, conflict, food insecurity, natural disaster, political unrest, isolation, and climate change. Individuals interested in participating were deemed eligible for participation if they had at least six months of working experience in their role. For the member checking IDIs, we selected new key informants from recent trainees in emergency response and those who had recently led an emergency response training. Contact details of prospective participants were extracted from the RRT database managed by LST.

All prospective participants were emailed a recruitment form summarizing the study and its goals and asking if they were interested in participation. In addition, the study team attended remote meetings of the global RRT Knowledge Network and RRT Working Group, where we introduced the study and notified them that they and their national colleagues were being emailed about the study. We followed up with interested individuals to schedule participation in a remote IDI or FGD via Zoom (Zoom Video Communications, San Jose, CA).

At the beginning of each remote data collection procedure, whether an individual interview, or a group process (focus group, workshop) we conducted a formal verbal consent process, reading to the participant(s) the same language as in the invitation letter emphasizing that participation was voluntary, any information they provided would be reporting anonymously, and that they could stop at any time. Those who consented again to participate were also given the option to turn off their cameras and delete their screen names.

Data collection

We developed a dynamic IDI guide with three sections. First, we asked participants to list all the important tasks performed by RRTs before, during, and after a health emergency. We recorded each freely elicited task on a form, and probed to ensure complete elicitations, and our clear understanding of the tasks described by the participant. Next, we asked participants to identify which of the tasks mentioned were the most critical; what it looked like to perform that task very well in their context; what personal capacities were necessary to learn to perform the task effectively; and how they had learned them. All IDIs were audio recorded with participants’ expressed consent and written notes were taken during the interviews. Full transcripts were created for each interview and focus group using the Zoom web meeting platform’s transcription software. Transcripts were reviewed for accuracy and completeness by the interviewer or facilitator immediately after each interview and focus group and audio recordings were referenced to correct all transcription errors. Transcripts were de-identified by deleting any appearing names and replacing them with a code. The code was connected to the participant only for logistics and management purposes during the data collection phase. Documents linking participants with their assigned codes were deleted during the data analysis phase.

Following the IDIs, we conducted FGDs with additional key informants. FGD participants were provided with a provisional set of skills and tasks compiled from the desk review and IDIs and were asked to complete a group sorting exercise using the Miro platform online.12 To participate in the FGD activity, the group of participants organized virtual sticky notes, each with one practice task on it, into categories that made sense to them. All participants in each focus group worked together until they established agreement on the categories into which the tasks could be organized. We then asked participants to name each of these categories, or domains, of practice tasks that they had created. Finally, after further revising the domains and practice activities into a draft competency framework, we conducted IDIs with four new key informants as a way of member checking to guide further revision.

Data processing and analysis

Desk review

Competencies and practice tasks from the desk review were tabulated by domain, or broad area of RRT practice, into a single reference table (Table 1).

In-depth interviews

Each IDI resulted in three lists of tasks. Data from the individual lists of tasks were consolidated into three combined lists referring to before, during, and after a health emergency. Tasks within each combined list were ordered based on the frequency with which they were mentioned (Table 2). We used participants’ commentary and explanations to fully understand the nature and boundaries of each task. When participants referred to the same task but with different phrasing, we merged these tasks with standardized language. We then used the reference table developed through the desk review and the consolidated combined task lists from the IDIs to compile the provisional set of competencies and practice tasks categorized into provisional domains to be refined during the FGDs. We did not share the research team’s provisional competency domains with the FGD participants.

FGDs and member checking IDIs

To analyse FGDs, we first listed the provisional competency domains identified through the systematic analysis of IDIs and those identified by the focus group members side by side, aligned by topic. We revised wording and collapsed common categories to create a refined list of domains (Table 3). We refined domains by 1) further simplifying and focusing domains through rewording; 2) decomposing large domains into two smaller domains; 3) differentiating competencies by actors (e.g. manager, member, trainer); and 4) defining specific roles requiring specialized expertise (Table 4). We then reviewed all unassigned competencies and practice tasks frequently identified in the desk review, IDIs, or FGDs that did not fit any of the existing domains and grouped them into additional domains. This resulted in the final set of domains and competencies to be included in the competency framework. Following this step, we shared the entire competency framework with the new key informants for their feedback.

RESULTS

Phase 1: Desk review

Results of the desk review included 8 different, partially overlapping sets of skills and practice tasks yielded from published competency frameworks and training materials (Table 1).

Phase 2: Qualitative findings

We emailed 47 invitations for IDIs; 14 agreed to participate. During attendance at remote meetings of the global RRT Knowledge Network and RRT Working Group we solicited participation for FGDs; 26 individuals participated in one of three FGDs (FGD 1 n=12, FGD 2 n=12, FGD 3 n=2). Due to the low number of participants, FGD 3 was held more as a small group discussion with the same field guide. Information from the four final IDIs was used to refine the domains, competencies, and practice activities in the competency framework.

Table 2 shows the frequency with which tasks and skills were mentioned. Of 15 IDI task lists, 4 were contextualized for COVID-19, one for foodborne outbreaks, and the rest generalized for any emergency. The range was 9-27 tasks per participant (average 17.6 tasks, median 18 tasks, and a total of 75 different tasks across all participants). We used a consensus cutoff point of a frequency of ≥4.

During the IDIs, participants described learning to perform the key tasks and leadership through trainings, desk manuals, but also through on-the-job mentored learning. Mentored learning was discussed as particularly important. Of note, three participants indicated that due to the turnover in their role, much of their learning was self-guided, making on-the-job mentored learning even more valuable. Interviewees often stated the importance of leadership and management in emergency situations. Leadership and management practices were described as highly varied across emergency contexts, critical for effective response, and difficult to learn to do well. When asked how interviewees learned leadership and management competencies, they most often stated they learned these on-the-job, without formal training.

Tables 3 and 4 illustrate the sequential analysis that led to the completed RRT competency framework. Table 3 presents the domains developed by the focus group participants with those developed in the desk review and the IDIs.

When comparing domains developed by focus groups, IDIs and desk review, we found domains to be largely consistent across stages of emergency response.

In Table 4, we reworded, collapsed and combined identical and similar domains. For example, “data collection, analysis, and reporting” was reworded to “collecting and analysing field data.” Additionally, some large domains were split into two smaller domains (e.g., “Preparedness, incident monitoring and surveillance” became “Detecting signals and assessing risk” and “Notifying and reporting”). Further analysis and synthesis of domains by the research team resulted in the development of core and role specific strata of competencies. Core domains included practice activities carried out by all RRT members, while Role-specific included more specialized practice activities conducted by some RRT members more than others. Each of these domains was then further classified by whether it was the primary purview of an RRT manager, trainer, or any member as shown in Figure 2.

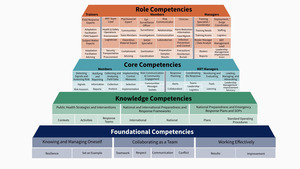

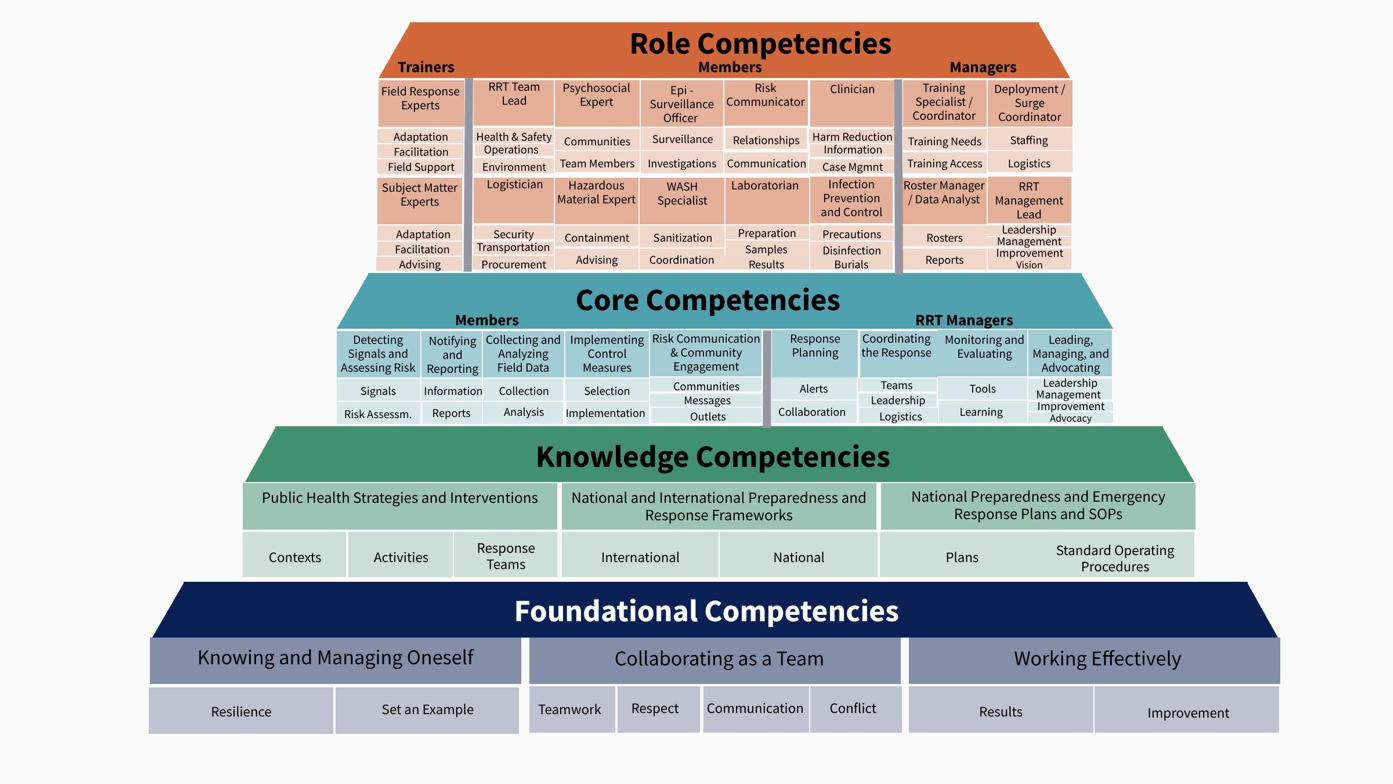

Last, drawing on unassigned desk review findings and competencies from IDIs, we defined two additional strata of knowledge and skills– knowledge-based competencies and foundational competencies. The former relate to acting upon discrete and practice-specific knowledge; the latter involve fundamental aspects of working in most public health roles and professions. We identified three Knowledge competencies, pertaining to possessing and acting upon discrete sets of knowledge and knowledge resources, and three universal, or Foundational competencies. This resulted in the 31-domain framework organized in four tiers (Table 5, Figure 2).

Findings from the member checking interviews did not alter the number of domains but provided details regarding how participants undertook practice tasks during an emergency response. These details helped finalize a framework specific enough to assess RRT workforce competency and guide training, without being so specific that it would not be applicable across geographic contexts or varied types of emergencies.

The final competency framework in Figure 2 presents domains from general to specific, beginning with foundational domains at the bottom and ending with role-specific domains at the top. In terms of granularity, Figure 2 lists only domains and competency titles; Tables 6, 7, 8 and 9 denote specific competencies. Behaviours that demonstrate each of the competencies are included in the final version of the framework and used to guide training development and continuous quality improvement efforts at the international, national, and subnational levels.

Foundational competencies are shared among roles in a given occupation as well as by others in related occupations; performance may look different across different roles, in different contexts, or during different kinds of incidents. Often referred to as “soft skills”, these competencies influence all other competencies and are associated with success across health care roles and professions (Table 6).

Knowledge-based competencies are shared among multiple roles and enable individuals to carry out tasks effectively; performance relates to having access to and being able to act upon the knowledge needed to serve in one’s role (Table 7).

Core competencies are performed in collaboration by individuals in multiple roles; their performance may look significantly different in different contexts or incidents. Individuals might focus on some core competencies more than others depending on their role. This tier includes distinct domains for RRT members and managers (Table 8).

Role competencies refer to specialized role-specific tasks performed by RRT trainers, RRT members, and RRT managers (Table 9).

DISCUSSION

The study was successful in eliciting a set of domains and competencies relevant for RRTs resulting in the development of a comprehensive framework of 31 domains and 78 competencies necessary for RRTs to master in order to respond effectively to public health emergencies. The framework’s organization into four tiers: foundational, knowledge, core, and role, addresses the most critical job-performance tasks for RRT members, managers, and trainers.

The framework’s tiered organization feature has been used to represent other dynamic models of foundational and technical competency (U.S. Department of Labor; WHO UHC Framework).10,19 The tiered model distinguishes the variations in roles among RRT members, managers, and trainers. The framework indicates, for example, that although all RRT Managers need to competently coordinate the response, those with specific Deployment and Surge Coordinator roles need specialized capability to develop plans for adequate staffing, logistics, and deployment. A tiered framework with multiple delineated roles can enable nuanced assessment of training needs and streamlined processes for onboarding of new members across multiple roles because training in overlapping competency areas can be shared.

In addition, the framework creates an opportunity to analyse available trainings to ensure that adequate opportunities exist for RRTs to learn to perform their roles effectively. Currently, WHO provides an RRT Training Programme consisting of 5 learning blocks on its Health Security Learning Platform.20 Analysis of available training using this framework could expose gaps and target future training. Further, monitoring and evaluation efforts at the closure of an emergency response could involve reflective competency assessment and aid continuous improvement efforts. WHO is in the process of developing, with the contribution of international partners, a monitoring, evaluation and learning guideline to support Member States efforts for assessing the efficiency and effectiveness of their RRT programmes.

We have identified additional themes that suggest attention. Given the difficulty in learning leadership and management competencies and the frequency of learning these on the job, without formal training, the WHO is currently implementing a Leadership in Emergencies Learning Programme for WHO staff.

Beyond their own training, RRTs should have the necessary knowledge and skills to contribute to the strengthening of their country’s capacities in terms of early detection and rapid response to public health events. This competency framework can play a crucial role in strengthening such country-level professionals.21 The framework can help guide training programs, professional development initiatives, and performance evaluations. It can facilitate professionals’ acquisition of the necessary expertise in epidemiology, risk assessment, communication, leadership, and coordination, thereby enhancing their overall capabilities in responding to public health emergencies.22,23 By examining existing training and feedback from participants, alongside a systematically developed competency framework, RRT program managers can revise and add to their suite of professional learning offerings. The competency framework can also be used to help new and experienced RRT members alike, by articulating in detail the kinds of knowledge and skills needed so that they self-reflect on the areas of practice they believe could be improved [24].

Limitations

Our desk review relied mostly on previously developed RRT guidance documents; a more comprehensive review of recent academic and grey literature would be useful to refine the competency framework. Although representatives from all WHO regions were invited to participate, we conducted the study with those who accepted the invitation, and this may have caused selection bias. Interviews were conducted primarily in English, with limited use of French, and this may have hindered the inclusion of participants who were more comfortable expressing their perspectives in languages other than English or French. Our participant group represented individuals from four out of six WHO regions. This could have overemphasized competencies needed in the represented regions or underemphasized competencies needed in the unrepresented regions. When robust recruitment was possible within regions, it was greatly facilitated by the regions’ key RRT training implementer, however, in the two regions not represented, no individuals held this position, challenging recruitment efforts. Therefore, future work could seek to improve the framework guided by input from regions not represented here, namely the Western Pacific Region and the Region of the Americas. However, the participants that were recruited represented all levels of RRT operations as well as a broad range of emergency and disaster circumstances and their responses had a high degree of alignment regardless of region. They showed ease with the conferencing software used and explained their points of view at length. While some participants were better dividers of larger tasks into their parts, there was agreement on the larger tasks by a majority. We used multiple research methods and reached high agreement among methods in the results obtained. We were careful to describe our methodology in detail allowing for reproducibility by other researchers, thus our findings should have high transferability to similar contexts. This reflection on our study leads us to believe that rigor was high and that we therefore reached high validity for the specific study context. However, we acknowledge that additional refinement of the framework would be a worthy pursuit as informed by additional use of the competency framework in the field across WHO regions.

This study of self-reported data from practicing RRTs contributes to the understanding and prioritizing of competencies from the emergency responders’ perspective and that of their managers. To estimate the degree to which each competency needs to be demonstrated and its effectiveness in a successful emergency response, a program evaluation study design could follow.

CONCLUSIONS

We developed the RRT competency framework to strengthen capacity for frontline responders to public health emergencies. This framework can assist WHO and Member States in identifying new appropriate training in improving performance management systems and in developing criteria and strategies to recruit new RRT managers, trainers, and members.

How participants learn matters. Alongside more focused training, an organized mentoring component could be especially valuable to support leadership and management components, as could be peer-to-peer mentoring opportunities structured around the competency framework.

Finally, although this competency framework is developed for RRTs, the framework and the methods used to create it, can be applied to support other frontline workers and global health emergencies workforce in general, such as community health workers and emergency medical technicians. For example, authors are currently using this method to develop a competency framework for community health workers (CHW), drawing on many of the foundational competencies needed across both RRT and CHWs.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. Stefan Baral at the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health who assisted in the development of the proposal that funded this work; we thank him for his insights. We are also grateful to the RRT Working Group members, and additional respondents including those from the RRT Knowledge Network, for their input on the development of the RRT Competency Framework and more broadly, for their support on the development of the RRT Training Programme. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Emergency Response Capacity Team, Division of Global Health Protection, for their financial support and technical collaboration on the development of the RRT Competency Framework and more broadly, for the development and implementation of RRT capacity building activities. Members of the Johns Hopkins University School of Education IDEALS Institute. The design and the protocol of this study was reviewed and approved by the Johns Hopkins University Homewood Institutional Review Board. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions, or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

Ethics statement

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Johns Hopkins University Homewood Institutional Review Board (IRB, HIRB00015381).

Data availability

De-identified interview and focus group data summaries available upon reasonable request.

Funding

This study was funding by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [cooperative agreement number GH0002225-03]. Article contents do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the Department of Health and Human Services nor does mention of trade names, commercial practices, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. The APC was funded by the Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Technology in Education.

Authorship contributions

Nicholas Gillon: study design, data collection, analysis and manuscript preparation. Paula Gomez: study design, data collection, analysis and manuscript preparation. Hind Ezzine: study design, data collection and manuscript preparation. Molly E. Lasater: study design, data collection, analysis, and manuscript preparation, Angela Omondi: manuscript formatting, Christopher Kemp: study design, Laura Beres: study design, Melinda Frost: manuscript revising and validation, Elli Leontsini: study design, data collection, analysis, and manuscript preparation. All authors critically reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final version for publication.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare no competing interests. The authors completed the ICMJE Disclosure of Interest Form (available upon request from the corresponding author) and disclose no relevant interests / declare the following activities and relationships.

Correspondence to:

Dr. Nicholas Gillon

Johns Hopkins University, School of Education

2800 North Charles St., Baltimore, Maryland

USA

ngillon1@jhu.edu