INTRODUCTION

Educational conferences play a critical role in advancing global health by addressing unique challenges and needs of providing care to patients in diverse settings. Specifically, emergency conferences address the challenge of providing acute care to critically ill patients– who represent a vulnerable population with distinct physiological needs. Therefore, caring for patients emergently requires specialized training and resources. Although there is diversity even amongst different hospital systems within the same country, there are key foundational components that are essential to any practice. An excellent and well-structured educational conference builds upon these core components while also tailoring the content to meet the individualized needs where these skills would be implemented.1

Educational conferences serve as platforms for an exchange of knowledge and allow healthcare providers to share evidence-based practices, innovative solutions, and strategies for managing and mitigating emergencies with improved outcomes. Additionally, they foster international cooperation and shared bidirectional learning.2 Equipping physicians in lower resourced settings with the latest research, clinical skills, and cross-cultural insights, emergency conferences contribute to building resilient healthcare systems, enhancing emergency crisis preparedness, and ultimately improving survival and quality of life for patients worldwide. Furthermore, with continued emphasis on communication and patient-centered care, these conferences hope to increase patient satisfaction and improve health service delivery.3

Similar to their counterparts in the United States, early-career doctors in Ghana are required to engage in continuing medical education (CME).4 CME is critical in any physician career, as it helps to provide essential learning opportunities within the ever-changing landscape of medicine. CME can be achieved through numerous methods including attendance at educational conferences. Ghanaian physicians report a scarcity of opportunities specifically tailored to address the unique needs of these practitioners during their initial years of practice.5 Ghanaian physicians also report that they have generally found difficulty in finding sufficient opportunities to fulfill their CME requirements.4 The Young Doctors Conference was created as a means of fulfilling CME requirements and to partner with local Ghanaian physicians to create a conference with educational components focused on advancing emergency care and communication skills in a practical manner for native Ghanaian physicians early in their career.

Other similar emergency care models exist in sub-Saharan Africa and have been shown to increase confidence in managing emergency care scenarios. The Basic Emergency Care Course from the WHO is an open-access course that has specifically been implemented in multiple countries in Africa and demonstrates significant improvement from pre-assessment to post-assessment scores.6 Additionally, studies show that this knowledge can be retained at 6 months and even 1 year after taking the course.7,8 More studies are needed to look at how this course impacts clinical practice and patient outcomes.6 The Young Doctors Conference is similar in that it is structured to provide emergency care skills and develop confidence in new physicians. However, it also seeks to address gaps in mentorship opportunities and collaboration amongst physicians in Ghana. In addition, the conference seeks to improve ‘soft skills’ like developing patient-physician relationships and increasing empathy. Lastly, the conference exists as an ongoing partnership between local physicians and healthcare workers in Ghana and counterparts in the United States that continues to flourish outside of the timeframe of the 3-day conference.

Furthermore, emergency care in Ghana is often hindered by limited resources, inadequate infrastructure, and a shortage of specialized training. Many newly qualified healthcare providers lack access to comprehensive, hands-on training in life-saving emergency skills, leading to significant gaps in the delivery of care.9,10 Because many hospitals are under-funded and lack the infrastructure to provide continuing education on life-saving skills, it is often left to the physician to seek out that ongoing education elsewhere.11 Gaps in this knowledge lead to poorer patient outcomes and increased deaths, highlighting the critical role of educational initiatives like the Young Doctors Conference, which provides focused education and practical training to enhance competency in emergency care.

The purpose of this paper is to highlight the structure and reported effectiveness of such initiatives and to serve as a model that can be replicated across other resource-limited settings.

METHODS

A non-governmental organization composed of a group of physicians, nurses, and other allied healthcare professionals that works to improve medical care in Africa hosts an annual conference (Young Doctors Conference) along with other CME opportunities. This conference is a 3-day event dedicated to enhancing life-saving care and specifically addresses the gaps in hands-on training and specialized education in emergency care that many professionals face in resource-limited settings. Open to newer physicians and nurses, as well as a small cohort of alumni professionals, the conference draws participants from different hospital systems across Ghana. The conference is mostly paid for through donations from fundraising efforts, with participants only required to pay a small fee to reserve their place, making it affordable for early-career participants.

Conference faculty consisted of both local and international healthcare professionals, fostering a collaborative and diverse educational environment. Ghanaian physicians and healthcare educators played a crucial role in providing region-specific expertise and contextually relevant training. This combination of local and foreign instructors promoted bidirectional learning, ensuring that training was both culturally appropriate and informed by a broad range of clinical experiences. By integrating expertise from multiple healthcare systems, the conference aimed to enhance the educational experience and equip participants with practical skills applicable to their clinical settings.

The basic structure of the conference (Table 1) each day was divided into large group/plenary didactic sessions, breakout didactic sessions, and hands-on skill-based training sessions. The large group sessions were designed to appeal to the multidisciplinary nature of the group and focused on topics like evidence-based care, quality improvement, triaging emergencies, and the humanistic aspects of medical care. The breakout didactic sessions were targeted towards the needs of each individual sub-group (e.g. first-time physicians or first-time nurses). The hands-on training sessions were targeted for all groups and included practice with basic life support, newborn resuscitation, communication skills, team building, and managing obstetrical emergencies. The aim for all of these sessions was to supplement the clinical and practical training that participants need but may not have access to in their home institutions. Lastly, the conference included time for networking between participants from various locations as well as with faculty, with the goal of developing enduring professional relationships.

To assess the impact and effectiveness of this conference, anonymous questionnaires were sent to all participants at the conclusion of each conference. There was no pre-assessment questionnaire done prior to the start of the conference. Questionnaires were sent to all participants to avoid any potential form of bias that may arise from selectively choosing participants and to obtain the highest number of possible responses. However, questionnaires were self-administered which may introduce a response bias. Questionnaires were developed and distributed to participants using SurveyMonkeyTM and the questions asked remained consistent across surveyed groups. The questionnaires were multiple choice so answers could be quantitatively computed. These questionnaires were designed to capture data on conference quality, participant satisfaction, and perceived value of the learning experiences. Additionally, they included short-answer questions to garner feedback to improve future conferences. Four years of questionnaire data were reviewed to identify trends, measure perceived value and satisfaction, and guide iterative conference improvements. Open-ended response questions were coded and analyzed utilizing thematic analysis. Major themes were identified and discussed. All data was anonymized from participants, and informed consent was obtained where appropriate.

RESULTS

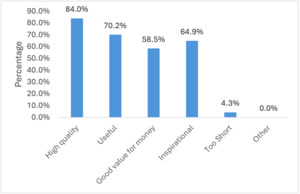

A total of 95 of the eligible 127 new physicians participated in the survey over the course of four years (response rate of 74.8%). The response rates from each individual year are 78.3%, 69.4%, 79.3%, and 74.4% respectively. The survey was non-mandatory, so any response or lack thereof is indicative of participant choice. Overall, the majority of respondents expressed high levels of satisfaction with the conference experience. Specifically, 93.6% of participants reported being very satisfied. The conference was frequently described using terms such as “high quality,” “useful,” and “inspirational” (Figure 1). The “other” column in Figure 1 consists of terms such as “overpriced”, “impractical”, “too long”, and “poor quality”.

When assessing how well the conference content and delivery methods met participants’ needs, 97.8% indicated that it met their needs either “extremely” well or “very” well (Figure 2). Additionally, 100% of participants rated the overall quality of the conference as either “very high” or “high.”

For specific training activities, all participants reported that Basic Life Support (BLS) training significantly increased their comfort in managing patients with cardiac arrest or breathing problems. Similarly, every respondent noted that Helping Babies Breathe (newborn resuscitation) enhanced their confidence in caring for ill newborns. Among those who attended the obstetrical emergency and Point-of-Care Ultrasound (POCUS) sessions, all agreed that these were valuable learning experiences.

Furthermore, the communication interactions simulation session was unanimously reported to be beneficial, with all participants affirming that it would improve their patient communication skills.

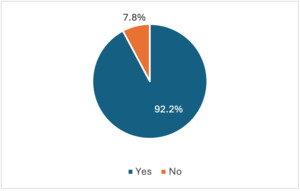

When asked about future engagement, 100% of respondents expressed a likelihood of attending future conferences. Additionally, 92.2% of participants indicated an interest in ongoing virtual training sessions (Figure 3), suggesting a strong preference for continued professional development opportunities.

Open-ended response questions were coded and analyzed utilizing thematic analysis to identify major themes. In discussing changes that participants hoped to make upon returning to their home institutions after leaving the conference, many described plans to focus on better communication and prioritizing patient needs. Participants emphasized the importance of enhancing communication skills to improve patient care and team collaboration. A common planned change was the desire for better communication with both patients and colleagues, in order to foster a more cohesive healthcare environment. Many expressed a desire to shift their approach to patient care, focusing on treating individuals as whole persons rather than merely addressing their diseases. Active listening, patience, and compassion were identified as essential qualities for strengthening the patient-provider relationship. Additionally, participants highlighted the importance of a more holistic approach to care, ensuring that patients remain the central focus of all medical interactions. By integrating these principles into their daily practice, attendees aimed to create a more empathetic, patient-centered healthcare system.

Feedback from participants highlighted key areas for potential improvement to enhance the impact of the Young Doctors Conference. Many attendees expressed a strong desire for more hands-on training opportunities, emphasizing the value of practical skill development in emergency care. Additionally, participants indicated that the current three-day format felt too packed and advocated for a longer duration and increased frequency of the event to allow for deeper engagement with the material. Another common theme was the need for greater mentoring opportunities, with participants seeking structured guidance from more experienced clinicians to further support their professional growth. Addressing these suggestions in future iterations of the conference could strengthen its effectiveness and ensure that it continues to meet the evolving needs of early-career healthcare professionals in Ghana.

DISCUSSION

The findings from this study highlight the significant impact and value of the Young Doctors Conference as a model to address critical gaps in emergency care training and communication for early-career healthcare professionals in Ghana. The overwhelmingly positive feedback from participants underscores the conference’s effectiveness in enhancing clinical skills, building confidence, and fostering a collaborative learning environment.

One of the most notable outcomes of the conference is the high level of participant satisfaction, with 93.6% expressing that they were very satisfied with their experience. The descriptors “high quality,” “useful,” and “inspirational” reflect the conference’s ability to deliver meaningful and practical content. The tailored approach, combining didactic and hands-on sessions, ensured that participants received comprehensive training aligned with their specific needs and practice settings.

The effectiveness of the hands-on training sessions, such as Basic Life Support (BLS) and Helping Babies Breathe, is particularly noteworthy. All participants reported increased comfort in managing critical situations such as cardiac arrest and newborn resuscitation, which are essential skills in emergency care. These findings suggest that the conference successfully fills a crucial gap in the practical training available to many Ghanaian healthcare providers, particularly in resource-limited settings.

Additionally, the unanimous positive feedback regarding the communication interactions simulation session highlights the importance of developing soft skills, such as effective communication, in delivering quality care. This session’s success points to the value of incorporating non-clinical skills training into medical education, which can lead to improved patient outcomes and physician-patient relationships.

The high likelihood of participants attending future conferences (100%) and the strong interest in ongoing virtual training sessions (92.2%) indicate a sustained demand for continuous medical education. This suggests that the Young Doctors Conference not only meets immediate educational needs but also fosters a culture of lifelong learning among participants. The interest in virtual training further emphasizes the need for accessible and flexible educational opportunities, particularly in resource-constrained environments. The conference’s structure, which promotes networking and the development of professional relationships, also plays a critical role in fostering a supportive community of practice. This is essential for creating a sustainable impact, as it encourages knowledge-sharing and collaboration beyond the confines of the conference.

However, the study also points to broader systemic challenges, such as limited resources and inadequate infrastructure, which hinder emergency care in Ghana. The success of the Young Doctors Conference underscores the importance of such initiatives in bridging these gaps. By providing focused, practical training and fostering international cooperation, the conference contributes to building resilient healthcare systems capable of improving care outcomes.

Despite its successes, the Young Doctors Conference also encountered several limitations and challenges that merit closer analysis. One key limitation was the compressed three-day schedule, which participants frequently noted did not allow sufficient time for deeper engagement with the material or extended hands-on practice. Additionally, the lack of pre-conference assessments and follow-up evaluations hindered the ability to measure knowledge retention and real-world application of skills over time. These gaps limit the program’s capacity to provide robust evidence of long-term impact. As baseline demographic characteristics were not collected, it also limits the generalizability of the findings. Logistical challenges such as participant travel and resource constraints also presented barriers to broader inclusion, particularly for practitioners from more remote areas. When compared to other global health initiatives—such as the WHO basic emergency care course or the WHO-supported Emergency Care Systems Framework—the Young Doctors Conference stands out for its NGO-led structure, hands-on practice, and strong integration of local expertise. However, its lack of longitudinal follow-up needs to be addressed in order to maximize long-term value and sustainability.

Plans for future iterations of this conference are built upon participant feedback. Central themes of change included extending the opportunities of this conference, particularly hands-on opportunities. By providing more hands-on educational training sessions throughout the conference, participants have greater chances to seek these opportunities out and gain skills needed to return to their respective hospitals with increased confidence. Since the schedule for this conference filled nearly the entire day each day, it is likely that the conference would need to be extended to accommodate such a request. This extension could include both offering the conference at more frequent intervals as well as increasing the number of days that the conference runs. Participants also reported a strong desire for ongoing virtual training sessions. While these sessions may not be hands-on in the same way that the conference provides, they may provide additional touch points for education and learning. These virtual training sessions can both supplement and add to the existing education that the conference provides. Finally, with a great desire for more mentorship opportunities, it is also possible to include virtual opportunities for ongoing mentorship. By regularly meeting with an experienced physician, early-career doctors in Ghana can continue to ask questions and develop a greater knowledgebase to best serve their patients.

Limitations of this study include a response rate of less than 100%. It is unclear whether the participants who chose not to respond could have impacted the results of this study. Participants who chose not to respond may have had negative things to say about the conference and this may have impacted the overall findings that the conference was helpful and had high levels of participant satisfaction. Additionally, although the surveys were sent at the conclusion of the conference to ensure that there was no pressure to reply with positive feedback, there may have been a bias in the way participants answered immediately after the conference as it is possible they may have felt obligated to respond in a positive manner. The survey was sent immediately at the conclusion of the conference as opposed to weeks or months in the future, which may be an additional limitation. Furthermore, no long-term data was collected and so it is unclear if these skills were retained over time and whether or not true practice changes were implemented after the conference. As this is a descriptive study, no causality can be inferred.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the Young Doctors Conference serves as an effective model for continuing medical education in resource-limited settings. Its success demonstrates the potential for similar initiatives to be replicated in other areas facing similar challenges. The conference not only enhances the confidence of early-career physicians but also contributes to the broader goal of reducing disparities and improving patient outcomes globally. The aim of the conference is to foster bidirectional learning and emphasize international collaboration and knowledge exchange, which ultimately strengthens the global health community. By combining hands-on training with interactive didactic sessions, the conference significantly increases participants’ confidence and ability to manage life threatening situations. The development of essential non-clinical skills like effective communication and teamwork further enhances the ability for physicians to provide excellent patient-centered care.

Further directions of research include examining the long-term impact of such conferences and on how the skills learned during these conferences are both sustained in the future as well as implemented in actual clinical practice. This could be done through longitudinal follow-up with participants on the retention of skills and on how they are integrated in the healthcare workplace. As this study only looks at a short-term snapshot of how conferences are beneficial, this type of future investigation would further solidify the true merit of such initiatives. Another future direction of research includes having participants take pre-assessment surveys to help greater analyze the magnitude of difference between skills before and after the conference. Future efforts should also focus on expanding access to such training opportunities and exploring innovative ways to sustain and scale these educational initiatives. These findings have direct implications for global policy, highlighting the need for formal integration of hands-on, contextually relevant education into national healthcare workforce development plans. Moreover, scaling such sustainable training models through public-private partnerships and policy-driven funding frameworks can help address critical skill gaps in emergency care worldwide.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge and appreciate the support of Africa Partners Medical as the sponsor of the conferences described in this manuscript.

Ethics statement

This study did not require approval from an Institutional Review Board (IRB) as it did not involve sensitive data that necessitated ethical review. All research procedures adhered to standard ethical guidelines for conducting academic research, ensuring the integrity of the data and the protection of privacy. All data used in the manuscript preparation was anonymized and informed consent was obtained from participants when relevant.

Data availability

Data was obtained via voluntary survey with participation in the survey serving as consent. Data has been anonymized and not available for public viewing/use.

Funding

None.

Authorship contributions

-

Jordan Holthe – study design, data review, original manuscript preparation and revision

-

Jason Homme – study design, data review, manuscript review and revisions

-

James Homme – manuscript review and revisions

Disclosure of Interest

The author(s) completed the ICMJE Disclosure of Interest Form (available upon request from the corresponding author) and disclose no relevant interests.

Correspondence to:

Jason Homme

Mayo Clinic

200 1st St SW

Homme.jason@mayo.edu