INTRODUCTION

Noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) are the leading cause of mortality worldwide, with a projected increase to nearly 69% of global mortality by 2030.1 Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has witnessed an epidemiological transformation of increasing mortality, moving from communicable to NCDs with cardiometabolic diseases rising in prominence after HIV/AIDS.1 This shift has primarily been attributed to urbanization and sedentary lifestyles. Cameroon, often referred to as “Africa in Miniature,” is not exempt from this burden. NCDs account for 31% of deaths in Cameroon, with cardiovascular diseases alone contributing to 14% of deaths.1 Diabetes mellitus, stroke, and ischemic heart disease rank among the top 10 causes of death in Cameroon, according to the CDC.2

Despite their increasing prevalence, cardiometabolic risk factors in the Cameroonian population remain poorly characterized. Hypertension (HTN) is increasing in prevalence, but awareness remains low. A large-scale population-based study revealed HTN prevalence ranging from 5.7% in rural areas to 47.5% in urban cities, with a national average of 31%.3 Diabetes mellitus (DM) prevalence in Cameroon is estimated at around 6% in 2018, with a lower prevalence in rural than urban settings. Obesity remains a leading CMD risk factor in Cameroon. In 2021, the age- and sex-standardized prevalence of overweight and obesity was 31% and 18.9%, respectively.4 Urban areas have higher rates of obesity (17.1%) and hyperglycemia (10.4%) compared to rural areas.5 Information on other CMD-related risk factors, such as dyslipidemia and anemia, remains limited in the adult Cameroonian population.

The challenges of poor access to screening, suboptimal diagnosis and management of CMDs, and overall lack of health understanding persist in the Cameroonian clinical setting. The increasing prevalence and unawareness of CMD-related risk factors highlight the need for intensified screening efforts. Early identification and appropriate management of asymptomatic and undiagnosed CMD risk factors are crucial to reduce morbidity and mortality. Another challenge is that Cameroon’s healthcare system is grossly underfunded and lacks the necessary infrastructure to address the growing burden of NCDs. Screening for CMDs is primarily available in primary care clinics in affluent urban areas, leaving a significant portion of the population underserved. This situation is not unique; numerous community and hospital-based screening initiatives across sub-Saharan Africa have sought to address this gap. Studies from Nigeria to Kenya have consistently revealed a high burden of previously undiagnosed NCDs, particularly hypertension, with awareness levels often below 50%.5,6 These programs have also demonstrated the feasibility of task-shifting models, where community health workers or nurses effectively conduct screenings, thereby expanding access in resource-limited settings.7,8 However, significant challenges remain, especially in ensuring linkage to care and long-term management for those identified as high-risk.

The Body Screening Project (BSP), a nonprofit organization established in 2020, aims to reduce the burden of CMDs in Cameroon through free screenings and increased awareness of CMD-related risk factors. The URBACAM-D program is a key initiative led by the BSP. The organization operates on the principle that community screenings can strengthen local healthcare systems, ease the burden on primary care providers, and improve patient outcomes by enabling early diagnosis and treatment.

This study aimed to determine the proportion of urban Cameroonians with previously undiagnosed and uncontrolled CMD-related risk factors, assess their associations, and provide health maintenance education. Additionally, the study evaluated the feasibility of the current screening strategy to inform public health policies. Feasibility in our context was defined as the ability to recruit participants, perform rapid point-of-care tests, and ensure referral when indicated.

METHODS

Study design and period

This observational study was conducted over two days in December 2024. URBACAM-D took place at Ndogbati Protestant Hospital in Site Sic, Douala, Cameroon. Site Sic is an underserved neighborhood near the Bessengue railroad station, situated in a previously swampy area. The screening location was chosen for its high public visibility and established safe environment. Health screenings were advertised through local clinics, churches, flyers, and social media.

Study setting and population

Ndogbati Protestant Hospital, located in Douala, Cameroon, serves as a critical healthcare facility, caring for approximately 14,000 patients annually. The hospital has three departments: Administrative and Support (Administration, Other), Clinical Services (General Surgery, Obstetrics-Gynecology, Pediatrics, Internal Medicine), and Laboratory. The screening location was chosen for its high public visibility and established safe environment. Health screening was advertised through local clinics, churches, flyers, and social media. Participants were urban residents who consented and enrolled in the study at the screening site. Eligibility criteria were as follows:

-

Inclusion Criteria: Any individual who voluntarily presented to the screening site during the two-day campaign and provided informed consent was eligible to participate. For participants under 18, assent was obtained along with informed consent from a parent or guardian.

-

Exclusion Criteria: Individuals who were unable or unwilling to provide consent or those presenting with acute medical distress that required immediate emergency care were excluded.

Study sampling procedure

Our screening consisted of point-of-care testing for DM, HTN, hepatitis, hypercholesterolemia, anemia, electrocardiogram (ECG) abnormalities, and obesity. Our screening was free and open to the public and participants were recruited consecutively among community members who voluntarily presented to the hospital site during the two-day screening campaign, with no restrictions on age, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, or religion. Participants were urban residents who consented and enrolled in the study at the screening site. A formal a priori sample size calculation was not performed, as a primary objective of this study was to evaluate the feasibility of the screening model within a fixed timeframe. The study therefore employed a convenience sampling approach. The final sample of N=172 represents the total number of participants recruited and screened within the logistical and temporal constraints of the event, and this was considered adequate for the study’s descriptive and exploratory aims.

Two blood pressure (BP) measurements (in mmHg) were taken on the right arm using an automated electronic BP machine, when the participant was seated and relaxed, with an appropriately sized cuff using standardized techniques (JNC 7 recommendations).9 Body mass index (BMI) was measured using standard procedures, where heights are in meters (m) and weights are in kilograms (kg) and calculated as follows: BMI = weight (kg) / [height (m) ∗ × height (m)]. Weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg with attendees wearing light clothing and standing on a portable scale that was calibrated daily. Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm with the participant standing using a stadiometer. A point-of-care 12-lead ECG was used to assess electrophysiologic abnormalities at rest in the supine position. Point-of-care biochemical assessments were performed to determine random blood glucose (RBG) using an Accu-Answer glucometer and RBG strips. Similarly, hypercholesterolemia and anemia were determined using the same machine and compatible strips. Viral hepatitis B and C were screened using a point-of-care machine. To ensure data quality and consistency, all screening personnel were nurses at the local hospital who were familiar with the equipment. They all underwent standardized training on data collection protocols. All equipment, such as digital scales and automated blood pressure machines, was calibrated or checked daily. A lead physician was on-site to supervise all procedures.

Attendees with detected CMD-related risk factors were offered a free medical consultation by a physician on-site. Patients diagnosed with HTN, DM, hypercholesterolemia, anemia, hepatitis, or obesity were provided with a written referral indicating the abnormal result. They were encouraged to follow up with a local primary care provider for confirmation and management. Giveaways, including coolers, sport bottles, coffee mugs, and healthy candies, were offered to attendees to promote healthy behaviors.

Data collection

Each participant completed a health questionnaire before the screening began (Appendix A). The pre-survey collected sociodemographic data on age, gender, level of education, town of residency, and occupation. The questionnaire also inquired about alcohol intake, smoking status, physical activity, recreational drug use, and fasting status. Another set of questions was asked at the end of the screening (Appendix B). The post-survey assessed participants’ awareness of any abnormal data found during the screening process, included PHQ-2 questions (depression reflected screening using the PHQ-2 tool, not a formal psychiatric diagnosis), a single question on loneliness, inquired about satisfaction with the screening process, and determined whether selected patients with abnormal data would follow up on their referrals. Trained medical assistants and nurses administered the surveys. Referral follow-up endpoints included whether participants attended specialist consultations and whether additional management was initiated (e.g., medication, lifestyle counseling).

Definitions

Obesity was defined as a BMI of 30.0 kg/m2 or higher; overweight was defined as a BMI of 25.0 to 29.9 kg/m2, normal if BMI is 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2, and underweight if BMI is less than 18.5 kg/m2.10 Patients were diagnosed with impaired fasting blood glucose (IFG) according to criteria outlined by the American Diabetes Association: a fasting plasma glucose (FPG) level between 100 and 125 mg/dL after not having anything to eat or drink (except water) for at least 8 hours before the test.11 Patients with a single unconfirmed FPG result ≥ 126 mg/dL or RBG ≥ 200 mg/dL in a patient with diabetic symptoms ( including extreme hirst, frequent urination, weight loss, blurry vision) were given a provisional diagnosis of DM. Anemia was diagnosed when point-of-care testing showed a hemoglobin value of less than 13.5 g/dL in a man or less than 12.0 g/dL in a woman.12 Hypercholesterolemia was defined as a total cholesterol level ≥200 mg/dL, which included borderline high (200–239 mg/dL) and high (≥240 mg/dL) classifications.13 WHO STEPS surveillance manual was used to assess physical activity: insufficient physical activity (defined as < 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activity per week, or equivalent), moderate-intensity activity, and vigorous-intensity.14 Current smoking was defined as consuming at least one cigarette per day. Alcohol consumption was defined according to CDC guidelines: lifetime abstainer, former regular drinker, current infrequent drinker, current light drinker, current moderate drinker, current heavier drinker.15 Recreational drug use was labeled as binary (yes or no) based on self-report. Hypertension (HTN) was classified based on the 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines, where an average of two BP readings showing a systolic BP ≥130 mmHg and/or a diastolic BP ≥80 mmHg was considered hypertensive.16 The measurement technique itself, including patient positioning and cuff sizing, followed the standardized procedures recommended by JNC 7 to ensure accuracy.9 The screening for Hepatitis B virus (HBV) involved detecting the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), while the screening for Hepatitis C virus (HCV) involved detecting the hepatitis C antibody (HCV Ab).17,18 Participants with reactive results for either test were referred to a local health facility for definitive confirmatory testing, such as additional HBV serologic markers or HCV RNA testing. The results of these confirmatory tests were beyond the scope of this study. Abnormal ECG findings included arrhythmia, left bundle branch block, prolonged QT, left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH), and atrioventricular (AV) blocks. Sedentary lifestyle was defined as engaging in less than 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity per week, consistent with WHO guidelines.

Informed consent

The consent form described the study’s purpose, the protocol to be followed, the benefits and risks of participation, and provided the option to not participate in the study without penalty. Participants’ questions were addressed before and after completing the screening surveys or the informed consent form. Participants signed digital informed consent forms. For this study, informed consent was explained in the participant’s preferred language. Attendees were free to obtain a copy of their signed consent if they so desired. They were informed that they would still receive a free health screening if they chose not to participate in the study. Participants were also informed of their right to withdraw independently from the study at any time without retribution. If a participant withdrew from the study, their data would be removed from our database and would not be included in the statistical analysis.

Ethics statement

URBACAM-D was conducted in collaboration and agreement with the Regional Human Health Research Ethics Committee for the Littoral in Cameroon, Ndogbati Protestant Hospital, Evangelical Church of Cameroon, and the Office of Human Subjects Research Institutional Review Boards at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

Data analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS version 25. Descriptive statistics were used to explore patients’ demographic and lifestyle characteristics. Continuous variables were summarized using means and standard deviations, while frequency and percentage were used for categorical variables. Chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests were employed to compare proportions, while t-tests were used to compare means of continuous variables between groups. To ensure clarity, the study variables were defined as follows:

-

Dependent Variables (Outcomes): The primary outcomes were the presence or absence of key cardiometabolic risk factors, defined as hypertension, obesity, and impaired fasting glucose.

-

Independent Variables (Predictors): These included sociodemographic factors (age, gender, marital status, income, education, employment), lifestyle factors (physical activity, smoking, alcohol use), and psychosocial factors (depressive symptoms via PHQ-2).

Multivariable logistic regression was used to assess the significant association between cardiometabolic risk factor outcomes and potential predictors. Variables with p<0.05 were considered statistically significant. Missing data were handled using a complete-case analysis (listwise deletion); for any given statistical test, only participants with complete data for all variables in that specific model were included.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic and cardiometabolic characteristics

Table 1 presents the sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants (N=172). Sixty-eight percent were women, and 26.2% were aged 65 or above. In terms of marital status, 43.2% were married, and 20.7% were widowed. For monthly income, 74.3% earned less than 50,000 FCFA (~$89) and only 2.9% earned 100,000-200,000 FCFA (~$179-$359). Regarding education, 18.1% had no formal education, defined as not having completed primary school, and 24.1% reported being unemployed.

Regarding cardiometabolic (CMD) related risk factors among participants. Blood pressure measurements revealed a mean systolic BP of 135.8 mmHg (SD=24.1) and a mean diastolic BP of 80.6 mmHg (SD=13.8), with 63(39.1%) having Stage 2 hypertension. Hemoglobin levels averaged 13.5 g/dL (SD = 2.0), with 16.2% of the subjects classified as anemic. Total cholesterol was normal in 86.2%, borderline high in 12.5% and high in 1.3% of participants. Blood glucose testing methods revealed that 84.9% of the participants were fasting, with a mean fasting glucose level of 89.9 mg/dL. Hepatitis B surface antigen was reactive in 2%, while hepatitis C antibodies were reactive in 2.6% of the study population. ECG abnormalities identified included 2.6% with arrhythmia, 5.2% AV blocks, 6.1% LVH, and 78.3% with no abnormalities.

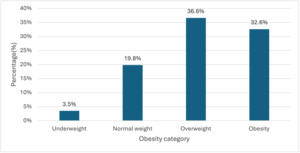

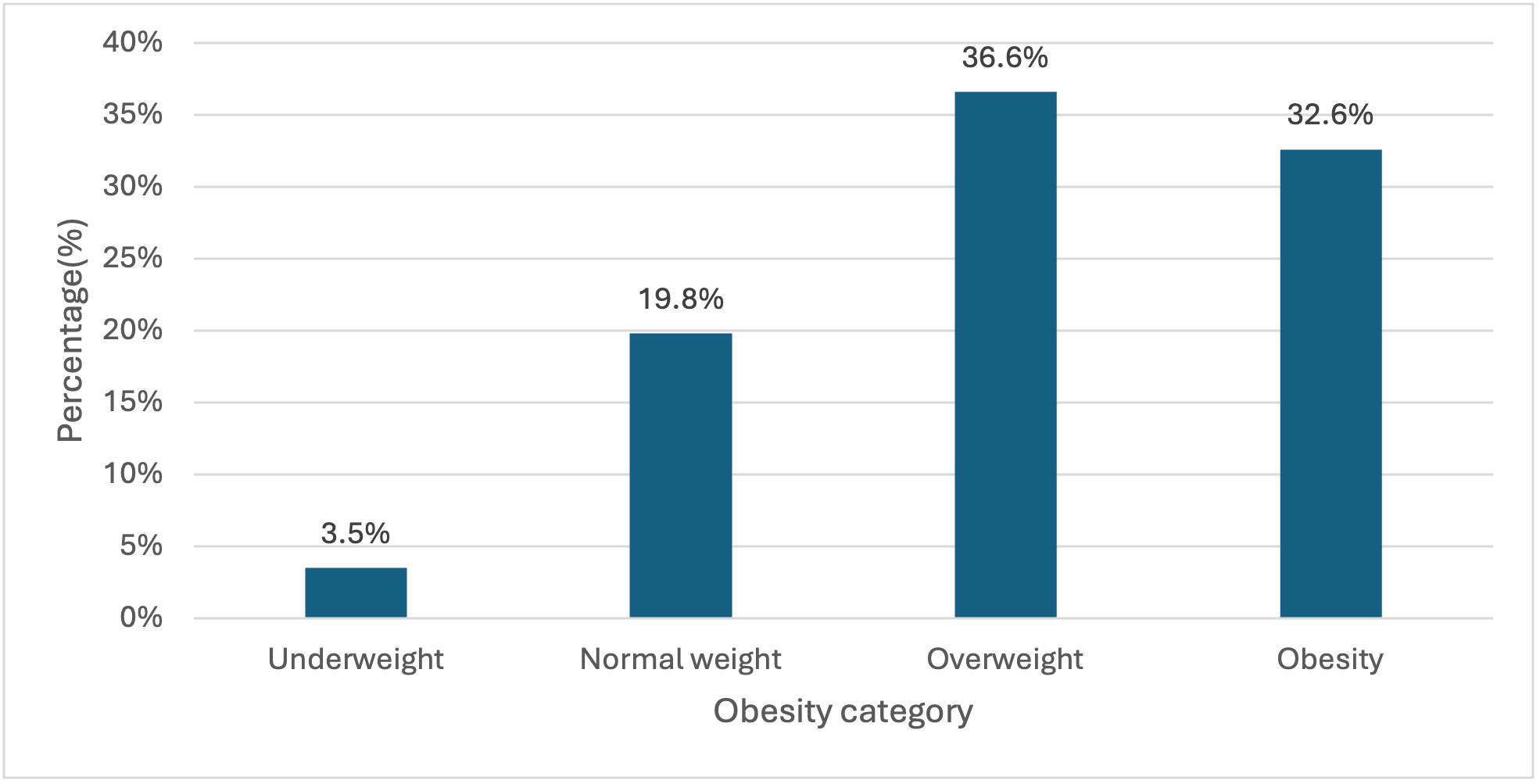

Out of 159 , 3.5% of participants were underweight, while 19.8% had a normal weight. Most of these participants were overweight (36.6%) and obese (32.6%) (Figure 1).

In terms of overall activities, a high proportion of participants 68(39.5%) did little to no exercise (sedentary lifestyle), and only 9(5.2%) were very active with frequent exercise. 50(29.1%) and 45(26.2%) practiced light and moderate active exercises, respectively (Figure 2).

Mental health and social well-being

Regarding PHQ-2 scores, 24.1% of participants scored ≥3 (Figure 3), indicating a positive screening for depression (Online Supplementary Material Table S3).

Analysis of the association between sociodemographic & lifestyle characteristics and CMD related-risk factors

Analysis of the association between sociodemographic & lifestyle characteristics and hypertension

After adjusting for variables in the multivariate logistic model analysis (marital status , employment status, overall activity and sitting for more than 30 minutes at a time), participants with low likelihood of depression (PHQ-2 scores <3) were 0.4 times less likely to be hypertensive than those with a higher likelihood of depression (PHQ-2 score ≥ 3) (95% CI 0.2-0.9, p=0.038). A full list of associations between sociodemographic and lifestyle characteristics and hypertension is in the online supplemental document, Table S2.

Bivariate analysis of the association between sociodemographic & lifestyle characteristics and impaired fasting glucose

Gender showed a statistically significant correlation with IFG in the bivariate analysis (p = 0.012). Variables with p-values less than 0.2 included in the multivariable analysis were: gender, minutes spent on moderate-intensity aerobic activity, minutes spent on vigorous-intensity aerobic activity, fasting status, and drinking habits (Online Supplementary Document, Table S4).

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with impaired fasting glucose

After adjusting the multivariate logistic model, female participants were 4.2 times more likely to develop IFG than male participants (95% CI 1.1-15.7, p=0.033) (Online Supplementary Document, Table S3).

Analysis of the association between sociodemographic & lifestyle characteristics and obesity

Table 3 reports the association between sociodemographic and lifestyle characteristics and obesity. After adjusting for variables in the multivariate logistic model analysis (age, gender, educational level, minutes spent on moderate intensity aerobic activity, overall activity, Minutes spent on vigorous-intensity aerobic activity ), women were 4.3 times more likely to be obese than men (95% CI 1.5-12.4, p=0.007).

DISCUSSION

Our hospital-based screening program revealed a high prevalence of cardiometabolic disease (CMD) among urban Cameroonians at the Ndogbati Protestant Hospital in Site Sic, Douala. Notably, more than one-third of the participants were diagnosed with Stage 2 hypertension, and over two-thirds were found to be overweight/obese. Additionally, one in four participants screened positive for depression, suggesting a potential psychosocial dimension to the CMD burden. These findings confirm the accelerating epidemiological transition in SSA, where noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) are replacing infectious diseases as the leading health threats.1,2 This epidemiological shift will pose significant economic and policy challenges for governments whose healthcare systems are already stretched.

Mental health and hypertension

We found a high prevalence of depressive symptoms (PHQ-2 ≥3 in 24.1%) among the study subjects. The total estimated number of people living with depression increased by 18.4% between 2005 and 2015.19 We also found that participants without depression had significantly lower odds of hypertension compared to those with depression. This finding highlights the need to integrate mental health assessment into NCD screening programs. Existing evidence from SSA shows that depression is both a contributor to and consequence of chronic disease, yet it remains largely undiagnosed in primary care.20,21 Our findings regarding mental health highlight the need to incorporate depression screening into NCD programs, from integrated health centres found in the rural communities to the central hospitals in urban settings including psychosocial workers (PSWs) who will participate in their counselling. Partnerships with non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and community-based organizations (CBOs) could also provide psychosocial support in settings with limited psychosocial workers via the integration and training of community health workers (CHWs).

Hypertension and factors associated

Our observed hypertension prevalence was slightly greater than previous reports from settings such as India (37.4%), Bangladesh (25.1%), and Nepal (18.4%),19 but consistent with African countries where the prevalence was high, with 30.6% in Nigeria5 and 49.7% in Gabon.8 72.5% of participants with elevated BP had no prior knowledge of hypertension. This finding aligns with broader systemic reviews in SSA reporting low awareness of hypertension, indicating a widespread issue of undetected CMDs. Generally, studies from North African countries showed the highest levels of awareness. The lowest prevalence of awareness in urban areas was 12.3% among slum dwellers in Nairobi.6 In our adjusted analysis, marital and employment status had no correlation with the onset of hypertension while the absence of depression significantly decreased the likelihood of developing hypertension. Meanwhile, studies by Mengome et al. and Kayima with colleagues have shown hypertension to be associated with gender, low education, obesity, smoking, and caffeine consumption.8,22 These findings highlight the increasing burden of hypertension together with its low awareness in the population, as well as the impact of psychosocial factors on cardiometabolic disease among adults.20 Non-pharmacological and lifestyle modifications are recommended for all individuals with elevated BPs regardless of age, gender, comorbidities, or cardiovascular risk status,16 and health professionals, even with no formal professional training, can be adequately trained to effectively screen for and identify people at high risk of cardiovascular disease.7

Obesity and factors associated

The high prevalence of overweight (36.6%) and obesity (32.6%) was consistent with another Cameroonian study that discovered the prevalence of overweight and obesity to be 39.6% and 24.1%, respectively,4 but higher than the 26.2% (overweight) and 23.8% (obese) prevalences found in Gabon.8 Women had a higher likelihood of being obese than men, a trend reported across developing countries in SSA.4,23 Even though in our adjusted model minutes spent on moderate and vigorous intensity aerobic activities were not significantly associated with obesity, these findings still underscore the urgent need for culturally tailored public health campaigns promoting physical activity in urban neighborhoods where risk factors are substantially higher than rural settings.8,24

Feasibility of the screening strategy

This hospital-based community observational screening, conducted over two days, demonstrated high feasibility regarding patient engagement (N=172) and rapid point-of-care testing. The strategy of using trained medical assistants and nurses for screening and survey administration proved to be a scalable and effective task-shifting model. The availability of physicians on-site to offer immediate consultations and referrals for participants with abnormal results emphasized the direct impact on community health, a critical element for effective policy. This strategy is consistent with findings that community health workers can effectively screen CMDs in various low and middle-income countries,6 and task-shifting models are potentially effective and affordable strategies for improving access to healthcare in resource-limited settings.25

The high rates of undiagnosed CMD risk factors underscore the current screening gaps in Cameroon’s underfunded healthcare system. The URBACAM-D model, which offers accessible screenings, directly addresses barriers to early detection, as identified in other analyses5,6,22-. The integration of psychosocial and biochemical assessments in one setting also demonstrates a feasible approach to comprehensive risk factor evaluation, advocating for a holistic approach within policy frameworks. Scaling this model in Cameroon’s underfunded health system will require embedding it within existing task-shifting frameworks. Evidence from HIV and mental health programs in Cameroon shows that nurses and community health workers can be effectively trained to deliver frontline screening and referral services, even in the absence of specialists.26 Integrating cardiometabolic screening into the minimum primary healthcare package, coupled with partnerships involving NGOs and faith-based organizations already active in NCD care, could mobilize additional resources. Furthermore, government endorsement through the Ministry of Public Health’s task-shifting policies, aligned with WHO recommendations, would ensure that such community screenings are sustainable and not isolated pilot projects.

Investments in portable point-of-care equipment and training for local healthcare workers can yield substantial returns in early detection, especially in underserved communities. Such investment could mitigate long-term economic burden of advanced CMDs on individuals and the healthcare system, which is currently ill-equipped to support the rising caseload. Policymakers should consider leveraging existing community structures, such as hospitals, churches, and schools, to optimize outreach and engagement for health screening programs.

Economic and social burden of undiagnosed CMDs

In low and middle-income countries such as Cameroon, where a significant portion of healthcare expenditure is out-of-pocket, the unawareness of CMDs often leads to delayed diagnosis and subsequent catastrophic health expenditures for families who can least afford it.26–28 The demographic data in Table 1, indicating that 74.3% of attendees earned less than 50,000 FCFA (less than $90) per month, highlights participants’ susceptibility to financial burdens. Early detection through programs like URBACAM-D can potentially avert costly urgent care and long-term disability, contributing to financial protection and improved household resilience. In addition, untreated CMDs lead to decreased workforce productivity and impedes national economic growth.26 Investing in preventative screenings and health education is thus a cost-effective strategy to maintain a healthy and productive population, aligning with WHO recommendations for NCD prevention.

Strengths and limitations

While URBACAM-D provides critical insights, its cross-sectional design limits causal inference. Additionally, the use of point-of-care testing, although practical for mass screening in resource-limited settings, may yield less precise results compared to laboratory-based assays. For policy, this suggests the need for confirmatory diagnostic services within a strengthened primary care system. Furthermore, the inclusion of participants only from one referral urban hospital limits the generalizability to rural populations and other urban settings in Cameroon.

While hypertension was diagnosed by averaging two BP measurements, they were taken on a single occasion. This approach deviates from the guidelines of the American College of Cardiology and the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee (JNC 7), which recommend at least two readings on separate occasions for a definitive diagnosis.9,16 We acknowledge this deviation, driven by the practical constraints of a high-volume, single-day community screening, and its potential impact on the true prevalence of diagnosed hypertension within our study.

Finally, mental health assessment, while limited to PHQ-2 due to time constraints, is a validated screening tool for depression, and its significant association with hypertension highlights the need for robust mental health referral pathways. Future research should prioritize longitudinal studies to evaluate the long-term impact and cost-effectiveness of integrated CMD and mental health interventions. Expanding screening efforts to a wider range of urban communities and studying the barriers to follow-up care will also be crucial in informing evidence-based health policies.

CONCLUSION

The study provides critical insights into the burden and determinants of cardiometabolic risk factors in an urban setting in Cameroon. The high prevalence of hypertension, obesity, and the onset of depressive symptoms highlights an urgent need for integrated, community and hospital-based interventions targeting both physical and mental health. Public health specialists and policy makers should prioritize infrastructure development and capacity building, especially in underserved urban areas where the burden is highest. Scaling up programs like URBACAM-D may significantly contribute to reducing the growing tide of NCDs in Cameroon and similar SSA contexts.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Newbell Protestant Hospital staff for their participation, as well as the Evangelical Church of Cameroon (EEC), the American Osteopathic Foundation, and the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine for their support in the donation process.

Data Availability

The fully anonymized data set supporting this study’s findings is available upon request. Requests for access to the data should be directed to the corresponding author.

Funding Statement

The American Osteopathic Foundation’s International Humanitarian Medical Outreach Grant and Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center Rajiv Thakkar Scholarship supported this initiative to provide free medical care to the local Newbell population.

Author Contributions

-

Emmanuel Tito: Conceptualization (lead); Methodology (lead); Funding acquisition (lead); Project administration (lead); Writing – review & editing (lead).

-

Ines Kafando: Methodology (supporting); Data curation (supporting); Writing – review & editing (supporting).

-

Fatima Halilu: Methodology (supporting); Writing – review & editing (equal).

-

Ope Olayinka: Writing – original draft (supporting); Validation (equal); Writing – review & editing (equal).

-

Anita Tito: Project administration (lead); Resources (lead); Supervision (supporting).

-

Melpsa Johney: Data analysis (lead); Resources(supporting); Validation (equal).

-

Stephanie Kenjio: Writing – review & editing (equal); Data curation (supporting); Project administration (supporting).

-

Saanvi Dixit: Methodology (supporting); Project administration (supporting); Writing – review & editing (lead).

-

Marium Rehman: Methodology (supporting); Writing – review & editing (supporting)

-

Oriane Taku: Methodology (supporting); Project administration (supporting); Writing – review & editing (supporting).

-

Gabriel Tchatchouang Mabou: Methodology (equal); Data curation (lead); Formal analysis (lead); Software (lead); Writing – review & editing (equal).

Competing Interests

The authors completed the ICMJE Disclosure of Interest Form (available upon request from the corresponding author) and disclosed no relevant interests.

Additional Material

This manuscript contains additional information as an Online Supplementary Document.

Corresponding Author

Emmanuel Tito, DO

Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Internal Medicine Department

5200 Eastern Avenue, Room 260

Mason F Lord Building

Baltimore, MD 21204

United States of America

Tel: (410) 550-0926

Fax: (410) 550-1069

E-mail: etito1@jh.edu