Gender-based violence (GBV) is a global crisis that disproportionately affects adolescents and young people, particularly in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).1 This vulnerability is shaped by systemic impunity, sociopolitical instability, and limited access to protective services. Each day, approximately 430 young people die from interpersonal violence, and 30% of girls aged 15–19 are victims of partner abuse.2 In the DRC, armed and inter-ethnic conflicts have plunged 27 million people into humanitarian need, including 7.3 million exposed to GBV .3 Between January and June 2022, 60,247 GBV cases were reported, 60% of which involved sexual violence (SV), primarily affecting women and children.4 North Kivu, South Kivu, and Ituri accounted for 87% of reported cases.5 In 2023, Médecins Sans Frontières treated over 25,000 GBV survivors, nearly two victims per hour,6 and 17,000 cases were recorded in North Kivu between January and May 2024.7 UNICEF reported a 37% increase in GBV in this province during the first quarter of 2023.8 These figures reflect both the acute crisis in conflict zones and the broader national scale of GBV.

Among GBV forms, SV is particularly concerning, especially in conflict settings where it is used as a weapon of war .9 In the DRC, 32% of women have experienced SV,10 and one in five girls suffered abuse before age 18.11 In 2012, 18,795 SV cases were reported, 89% of which were gang rapes.12 A 2013 study in Lubumbashi found that 94% of SV victims were girls aged 14–17.13 These data underscore the age-specific vulnerability of adolescent girls, exacerbated by institutional fragility and impunity for perpetrators.14 Strengthening protection mechanisms, improving access to justice, and raising community awareness are essential.15 Education, provider training, and legal reform are key levers to combat SV.16 An integrated approach medical, social, and judicial, is needed to ensure survivors receive appropriate support and fair justice.17

Despite extensive research in conflict-affected provinces, urban centers like Kinshasa remain underrepresented in GBV literature. As the capital and largest city, Kinshasa presents distinct vulnerabilities: overcrowding, poverty, and limited access to justice and health services. This study aims to assess the prevalence and determinants of SV among adolescents aged 15–24 in Kinshasa.

METHODS

Study Site

Kinshasa, the capital of the DRC, spans 9,965 km² and had an estimated population of 17,032,300 in 2024 (14). The city faces major health challenges, including SV and infectious diseases such as HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis.15 The healthcare system is overburdened and underfunded, limiting access to quality care. Infrastructure gaps and inaccessible services particularly affect low-income communities.16 Young people face barriers to education and employment, while stigma and discrimination remain widespread.15

Study Design

This study is a secondary analysis of data collected in 2016 during a gender-based violence (GBV) survey conducted in Kinshasa by the National Adolescent Health Program (PNSA), with technical and financial support from PATHFINDER. The secondary analysis focuses specifically on sexual violence (SV) among individuals aged 15 to 24, using relevant variables related to sociodemographic characteristics, sexual history, and SV awareness.

Study Population and Selection Criteria

The study population consisted of 1,675 adolescents and young people aged 15 to 24 years residing in Kinshasa. This age range, while broader than the WHO/UN definition of adolescence (10–19 years), was selected to align with national programmatic priorities and the operational scope of the original dataset. Inclusion criteria were: permanent residence in Kinshasa, age between 15 and 24 years, and ability to provide informed consent. Adolescents with cognitive impairments or those unable to complete the interview were excluded. Only one eligible adolescent was selected per household to ensure individual-level representation and avoid intra-household clustering.

Sampling

A three-stage probability sampling method was used to ensure representativeness across Kinshasa’s diverse urban zones. In the first stage, municipalities were selected as primary sampling units using probability proportional to size (PPS). In the second stage, neighborhoods or health areas within these municipalities were randomly selected as secondary units. The third stage involved systematic selection of individual plots within each selected neighborhood.

Within each plot, households were identified using a random sampling interval based on the total number of eligible households. A household listing was conducted, and one adolescent aged 15–24 was randomly selected per household using a standardized randomization method. If the selected adolescent was unavailable after two scheduled visits or declined participation, the household was recorded as a non-responder. Replacement households were then selected using the same interval procedure to maintain sampling integrity and target sample size.

Variables of Interest

The dependent variable was lifetime experience of SV, defined as any non-consensual sexual act (rape, assault, exploitation, harassment) disclosed by adolescents aged 15–24. It was coded as 1 (yes) or 0 (no). Due to dataset limitations, disaggregation by severity or timing was not possible. Independent variables included age group (15–19 vs. 20–24), age at first sexual intercourse (<18), gender, marital status, occupation, education level, religion, and awareness of SV. These were recoded for logistic regression with reference categories.

Data Collection

This study uses 2016 data from the DRC National Adolescent Health Program, covering adolescents and young adults aged 15–24. Although the age range differs from WHO/UN definitions, it aligns with national priorities. Despite its age, the dataset remains the most recent and representative for Kinshasa. Structural drivers of gender-based violence—poverty, inequality, and weak institutional response—persist, making this a valuable baseline for future research. Data were collected via structured questionnaires on sociodemographic characteristics, sexual violence awareness, and access to sexual and reproductive health services, including STIs and HIV.

Data Analysis

All collected data were processed using SPSS version 27.0. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the prevalence of sexual violence and the distribution of key sociodemographic variables. Bivariate analyses were conducted using chi-square tests to explore associations between sexual violence and independent variables such as age, gender, marital status, education level, occupation, religion, age at first sexual intercourse, and awareness of SV. Logistic regression was applied to assess the strength of these associations and identify significant predictors. All statistical tests were interpreted at a 0.05 alpha significance level, ensuring robust and reliable inference from the data.

Ethics Considerations

Informed consent was obtained from all participants. For minors, assent was paired with parental or guardian consent, in accordance with national ethical guidelines. Interviewers were trained to handle sensitive disclosures with confidentiality and empathy. Participants disclosing SV were referred to appropriate medical, psychological, and legal services. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Kinshasa School of Public Health (Ref: ESP/CE/80/2025).

RESULTS

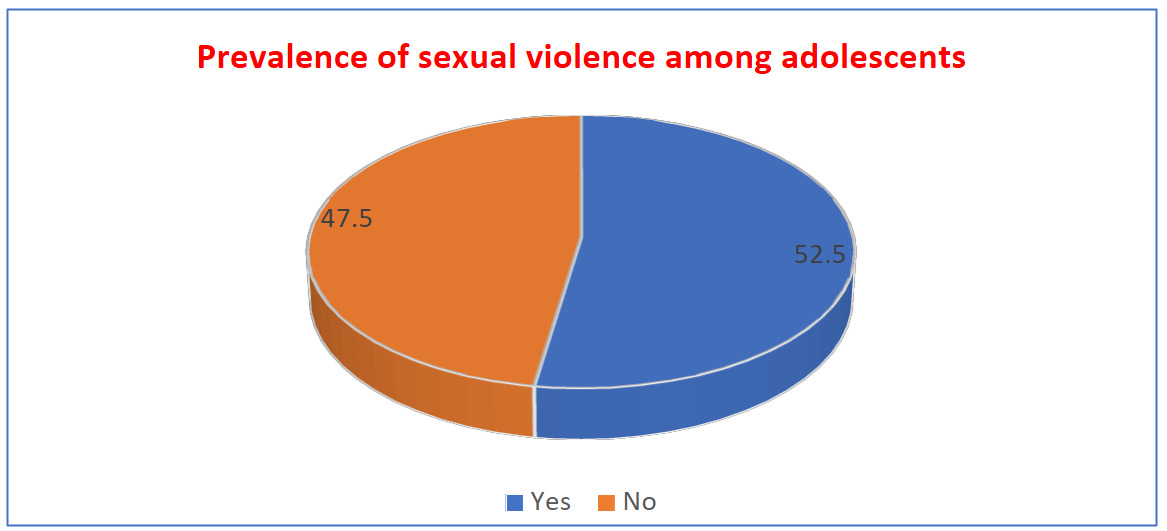

This study reveals a concerning prevalence of sexual violence (SV) among adolescents aged 15–24 in Kinshasa, with 52.5% reporting lifetime experience of SV. As shown in Figure 1, this means that over one in two adolescents in the surveyed health zones have been victims, underscoring the scale of the issue. This high rate reflects both the vulnerability of urban youth and systemic gaps in protection, justice, and prevention (Figure 1).

Sociodemographic data indicate that most respondents are aged 20–24 (59.2%), single (93.6%), and still studying (60.6%). Additionally, 74% live in households with five or more people, suggesting dense living conditions that may heighten exposure to risk (Table 1).

The most frequently reported perpetrators are individuals from the neighborhood (33.5%), followed by family members (9.0%), highlighting the proximity of threat and the presence of abuse within domestic environments (Figure 2). These findings suggest that SV is not only a public safety issue but also a community and familial concern.

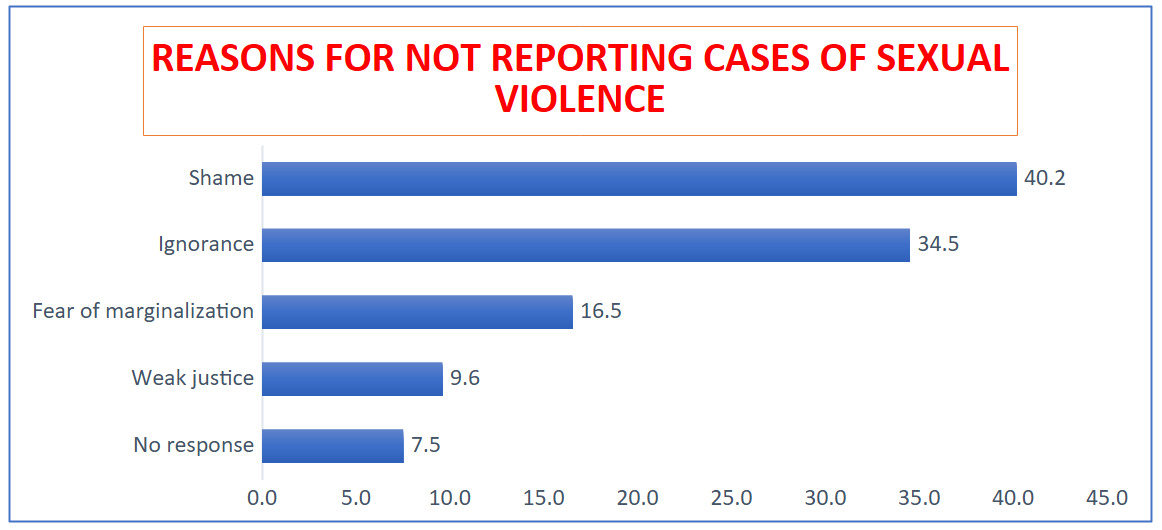

Barriers to reporting are dominated by shame (40.2%) and ignorance (34.5%), indicating that stigma and lack of awareness continue to hinder disclosure (Figure 3). Although the study did not quantify unreported cases, future research should incorporate disclosure metrics to better assess the hidden burden of SV.

Awareness of SV is widespread, with 97% of respondents indicating prior knowledge. Friends (21.3%) and radio (13.3%) are the main sources of information (Table 2), pointing to reliance on informal channels and gaps in institutional communication.

Bivariate analysis shows SV is more prevalent among adolescents aged 20–24 (55.7%), those with early sexual debut (<18 years), males (56.3%), workers (65.7%), and those without religious affiliation (75.0%). Prevalence also increases with education level, reaching 56.0% among university students. Significant associations were found with age (p=0.002), sex (p=0.002), occupation (p=0.014), religion (p=0.04), sexual experience (p=0.001), and awareness of SV (p=0.001) (Table 3).

Multivariate logistic regression identified key determinants: being male (OR=0.621, 95% CI 0.478–0.806, p=0.001) and having heard about SV (OR=0.037, 95% CI 0.005–0.280, p=0.001) were protective. Conversely, affiliation with the Catholic Church (OR=2.262, p=0.031), revivalist churches (OR=2.084, p=0.041), and prior sexual experience (OR=7.241, p<0.001) significantly increased SV risk (Table 4).

Overall, the results highlight the multifactorial nature of SV risk and the need for integrated, evidence-based interventions targeting both individual and structural determinants

DISCUSSION

This study reveals a significant prevalence of sexual violence (SV) among adolescents aged 15 to 24 in Kinshasa, with over half (52.5%) reporting lifetime experience. While this figure underscores the urgency of addressing SV in urban settings, the extent of unreported cases remains unknown, as disclosure behavior was not directly measured. Key associations such as early sexual initiation, religious affiliation, and prior sexual experience, suggest heightened vulnerability, while male gender and prior awareness of SV appear protective. These findings must be interpreted with caution, as they may reflect underlying socioeconomic, educational, or cultural factors not fully captured in the dataset.

High Prevalence of Sexual Violence in Kinshasa

The reported SV rate of 52.5% (Figure 1) highlights the widespread nature of abuse among adolescents, despite ongoing awareness and prevention efforts.17–19 This figure may be influenced by self-reporting bias and the broad definition of SV used, which included harassment, exploitation, and assault. Comparative studies across sub-Saharan Africa show similar patterns: Mabaso et al.20 reported 40% in South Africa, Rwenge et al.21 found 45% in Senegal, Ayen and Brouwere22 documented 48% in Uganda, and Nimaga et al.23 reported 55% in Togo. However, methodological differences such as sampling strategies, SV definitions, and age ranges limit direct comparability.

These findings suggest that current strategies to combat SV have not achieved sufficient impact. Adolescents remain inadequately informed about SV and its consequences.24 Policy responses must be tailored to Kinshasa’s urban realities, using local data to design interventions that reflect specific vulnerabilities. While parents,25 schools,26 and healthcare institutions25 are considered reliable sources of sexual health information, this study shows that adolescents primarily rely on peers (21.3%) and radio (13.3%) (Table II), revealing gaps in institutional outreach and structured education.

Factors Associated with Sexual Violence Among Adolescents Aged 15 to 24

This study identifies two main categories of factors influencing sexual violence (SV) among adolescents in Kinshasa: protective factors and risk factors.

Among the protective factors, male gender stands out (OR = 0.621, 95% CI 0.478–0.806, p = 0.001), indicating that male adolescents are approximately 40% less likely to experience SV compared to their female counterparts. This discrepancy may reflect entrenched sociocultural norms and gender roles in Congolese society, where girls are disproportionately exposed to high-risk environments such as agricultural labor, water collection, market activities, and domestic work.27–31 These tasks often place girls in unsupervised settings, increasing their exposure to potential perpetrators. Moreover, cultural restrictions and stigma frequently silence girls, especially when abuse occurs within the family circle.30–33 Dahourou et al.24 similarly observed in West Africa that adolescent girls, particularly those living with HIV, face compounded vulnerability due to stigma and limited autonomy—though this specific dimension was not captured in Kinshasa.

The second protective factor is awareness of SV (OR = 0.037, 95% CI 0.005–0.280, p = 0.001). Adolescents who had prior knowledge of SV were significantly less likely to report victimization. This finding underscores the importance of structured education and awareness campaigns delivered through schools, families, media, and community platforms.17,18,34 When adolescents are informed about SV, they are better equipped to recognize abusive behaviors, assert boundaries, and seek help. However, the protective effect may also be influenced by confounding factors such as education level and media access, which were not fully controlled in the analysis.

On the risk side, religious affiliation emerged as a significant determinant. Adolescents affiliated with the Catholic Church (OR = 2.262, 95% CI 1.964–5.308, p = 0.031) and revivalist churches (OR = 2.084, 95% CI 1.914–4.750, p = 0.041) were twice as likely to experience SV. This association may reflect complex dynamics, including stricter behavioral expectations, limited sexual health education, and reluctance to report abuse due to religious stigma. It is also possible that adolescents in these communities are less likely to engage in consensual sexual relationships, making them more vulnerable to coercion. While religion itself is not a direct cause, its influence on social norms and disclosure behavior warrants deeper qualitative investigation.

Prior sexual experience was the strongest predictor of SV (OR = 7.241, 95% CI 3.569–10.945, p < 0.001), increasing the likelihood of victimization sevenfold. This finding raises questions about temporality and measurement overlap whether sexual activity preceded SV or resulted from it. Rwenge21 emphasizes the risks associated with early and unprotected sexual debut, while Kuchukhidze35,36 links SV exposure to increased vulnerability to HIV infection. Although these studies do not directly address religious influence, they reinforce the protective role of informed sexual health education.

In sum, adolescent vulnerability to SV in Kinshasa is shaped by intersecting behavioral, social, and structural factors. These findings highlight the urgent need for comprehensive sexuality education, safe and confidential reporting mechanisms, and community-based prevention strategies tailored to the urban realities of Kinshasa.

Underreporting and Barriers to Disclosure

Underreporting remains a major concern. Shame (40.2%) and ignorance (34.5%) were cited as key barriers to disclosure (Figure 3), yet the dataset did not quantify the proportion of unreported cases. Research by Nimaga et al.23 in Mali and Stover et al.27 across sub-Saharan Africa confirms that stigma, institutional mistrust, and religious norms hinder disclosure. In Kinshasa, these barriers are compounded by limited access to justice and financial constraints, particularly in low-income households. Reporting often leads to arrest but not reparations, discouraging victims from seeking help. Strengthening referral systems, subsidizing legal aid, and training frontline workers in empathetic response are essential policy priorities.

Strengths and Limitations

This study offers several strengths. The use of a large, randomly selected sample enhances representativeness and provides a robust baseline for future research and policy development. The inclusion of diverse sociodemographic variables : age, gender, education, occupation, religion, and sexual history, enables a nuanced analysis of SV determinants. The identification of both protective and risk factors through multivariate regression adds depth and highlights actionable entry points for intervention. By focusing on Kinshasa, a non-conflict urban setting, the study fills a critical gap in GBV literature, which often centers on conflict-affected regions.

Nonetheless, limitations must be acknowledged. The cross-sectional design restricts causal inference. Self-reported data may be affected by recall bias and underreporting due to stigma. The use of 2016 data limits temporal relevance, as Kinshasa’s sociopolitical landscape may have evolved. Key confounders such as socioeconomic status, family structure, and exposure to violence were not fully controlled. The SV classification lacked granularity, preventing differentiation by severity or timing. Despite these constraints, the study provides valuable insights into adolescent vulnerability and lays the groundwork for future longitudinal and mixed-method research to inform targeted, context-specific interventions

CONCLUSIONS

This study reveals a high prevalence of sexual violence (52.5%) among adolescents aged 15–24 in Kinshasa, exposing persistent structural vulnerabilities. Although the age range diverges from WHO/UN standards, it aligns with national priorities and reflects the dataset’s operational scope. Shame and limited awareness remain key barriers to disclosure, while religious affiliation and prior sexual experience are significant risk factors. Despite relying on 2016 data, the findings provide valuable guidance for addressing adolescent vulnerability. To reduce this risk effectively, national strategies must prioritize comprehensive sexuality education, community-based prevention, and strengthened institutional accountability.

Ethics Approval

This study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the School of Public Health, University of Kinshasa (Approval No: ESP/CE/80/2025). All procedures complied with ethical guidelines for research involving human participants.

Consent to Participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their legal guardians prior to inclusion in the study. Participation was voluntary and anonymous.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable. The manuscript does not contain any individual person’s data in any form.

Availability of Data and Materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

We express our sincere gratitude to all the health professionals who participated in this study. We also acknowledge the valuable collaboration of the leadership of the National Adolescent Health Program for their guidance and institutional facilitation. Special thanks go to the Executive Committee of the School of Public Health, University of Kinshasa, for granting the necessary authorizations and for their continued academic and ethical support throughout the research process.

Authorship Contributions

Constantine Buziku Mambueni is the principal author who conceptualized and drafted the main research protocol, which was validated by the facilitator Dieudonné Mukendi Mpunga. Bernard-Kennedy Nkongolo Mukendi conducted the data analysis and interpretation. Noél Kipulu Katima and Fidèle Mbadu Muanda contributed to refining the content and formatting of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version in accordance with ICMJE authorship criteria.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The study was conducted as part of the requirements for the Master of Public Health degree at the University of Kinshasa.

Conflict of Interest

The authors completed the ICMJE Disclosure of Interest Form (available upon request from the corresponding author) and declare no competing interests.