INTRODUCTION

Over the past decade, the global response to HIV and AIDS has achieved remarkable results, with efforts now focused on sustaining these gains and eliminating HIV as a public health threat by 2030 [Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS1]. Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), which has the largest number of individuals living with HIV, has experienced the most significant progress. Between 2010 and 2023, the region experienced a 59% reduction in new HIV infections and a 57% decline in AIDS-related deaths.2

Despite the progress made in the fight against HIV and AIDS, significant financial investments are still necessary to maintain and build upon current achievements. UNAIDS estimates that approximately $12 billion was needed in 2024, increasing to $17 billion by 2030.3 The success of the HIV response in most SSA countries has depended primarily on external support. However, this reliance on external funding introduces a fragility that could threaten the long-term sustainability of these gains.3 Therefore, it is essential to identify domestic finances to ensure the continuation of the response.

Debt servicing now consumes more than 50% of government revenues in several SSA countries, including Uganda.3 Proposals to suspend debt repayment or offer relief are considered vital means to liberate domestic resources that can be allocated to address HIV and AIDS.4 Even with debt relief, for instance, Zambia is projected to dedicate two-thirds of its budget to debt servicing from 2024 to 2026.5 This pressing financial reality emphasises the critical necessity for bold economic reforms and sustainable fiscal policies that prioritise domestic funding for HIV initiatives.

Uganda has made significant progress in combating HIV, with 90% of people living with HIV (PLHIV) being aware of their status by the end of 2022. Among those, 94% received antiretroviral therapy (ART), and 72% maintained a suppressed viral load.5 However, 85% of national HIV response funding comes from external sources. In 2020, $566.6 million was spent on HIV and AIDS, with PEPFAR contributing 62% and the Global Fund contributing 23%.5

The prevention of new HIV infections remains crucial for the sustainable management of the HIV epidemic. Interventions such as voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC) are not only highly cost-effective but also cost-saving in the fight against HIV, even in the context of high antiretroviral therapy coverage.6 National examples, such as the HIV Investment Case for South Africa7 and the optimisation of HIV prevention and treatment in Eswatini,8 demonstrate the cost-effectiveness of the VMMC as a key HIV prevention strategy. Furthermore, out-of-pocket payments for HIV prevention could serve as a means to address shortfalls in domestic HIV funding, particularly if external resources decline. There is evidence to suggest a notable willingness to pay for HIV services, with estimates ranging from 34.3% to 97.1%.9

Recognising that not all males needing VMMC can afford the procedure, exploring both the ability to pay (ATP) and willingness to pay (WTP) for VMMC services is crucial. By identifying the factors that influence individuals’ decisions regarding payment, health policymakers can effectively target those who are both able and willing to pay for fee-for-service VMMC. This approach would help conserve public resources for individuals who cannot afford the service, ultimately optimising the use of available funds. This study aims to evaluate the ability and willingness to pay for VMMC services beyond donor support, serving as a mechanism for domestically funding male circumcision as a preventive strategy against HIV in Uganda.

This study is based on two theoretical frameworks: 1) basic economic theory and 2) the theory of planned behaviour (TPB). Basic economic theory suggests that forward-thinking individuals consume products or services that improve their welfare while minimising costs.10 According to this theory, individuals will likely purchase healthcare goods, such as voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC), based on their expected utility. Potential consumers of VMMC will be willing to pay if they believe the anticipated benefits outweigh the associated costs and discomfort, provided they have disposable income and sufficient knowledge about VMMC. However, this economic theory has faced criticism for its assumption of rational behaviour, as human decision-making is not always rational.11,12 Moreover, various factors beyond income and knowledge can limit individuals’ choices, indicating that economic theory alone may not fully explain the motivations of behaviours such as purchasing VMMC. For example, a study conducted in Kenya reported that while 62% of participants had the financial means to afford VMMC, only 42% expressed a willingness to pay for it.13

The second theoretical framework used in this study helps understand additional factors influencing decision-making beyond income and knowledge. The theory of planned behaviour14 suggests that behavioural intention, such as the intention to pay for VMMC, is shaped by three key components: an individual’s attitude towards the service, the influence of subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control. Attitudes represent a person’s overall evaluation of a situation; subjective norms refer to the impact of peer influences on the individual, whereas perceived behavioural control (PBC) relates to an individual’s self-assessment of their ability to engage in the expected behaviour.15

METHODS

Study design, sample size, and determination

A sequential mixed-methods study design was employed, beginning with a quantitative phase followed by a qualitative component. The research was conducted between November 2021 and June 2023, focusing on adult males aged 18 to 65 years. The quantitative sample comprised 496 participants, determined via the Cochrane 1963 formula for large populations.,16 such as the VMMC target for Uganda of 6.9 million.17 Since this was not a clinical trial, the clinical trial number is not applicable.

Recruitment of respondents, data collection and management

Owing to the ongoing COVID-19 restrictions, study participants were recruited virtually from a database that reflects Uganda’s general population. This database is compiled and regularly updated by the independent research organisation, the International Growth Research and Evaluation Centre (IGREC).18 The database contains data from all regions of the country, with more than 10,000 respondents representing the general population in Uganda. The people in the database are randomly selected with quotas that mirror the general population for age, sex, religion, employment and residence. It is used in various activities, including market research, opinion polls, brand research, monitoring and evaluation, and academic research. The participants agreed to participate in the study and received a reimbursement of UGX5000 ($1.4) in the form of phone airtime from IGREC as a token of appreciation. After an initial random selection, individuals were contacted and invited to participate in the study via telephone calls. Three days following the initial outreach, those participants who were available and expressed interest were provided with information about the study and invited to join. The participants who consented to participate were guided through the consent process and asked to provide verbal approval. Recruitment continued until the necessary quantitative sample size was achieved and saturation was reached for the qualitative component of the study.

Quantitative data were gathered through a structured questionnaire adapted from a prior study that examined the willingness to pay for antiretroviral drugs among HIV and AIDS clients in southeast Nigeria.19 The questionnaire was tailored to align with the study’s objectives and context and was piloted prior to implementation. Qualitative data were obtained through semi-structured interviews. The interview questions were informed by preliminary findings from the quantitative phase of the study, as well as the identified gaps in the literature. In-depth interviews continued until saturation was reached. Data collection was conducted virtually, and all equipment utilised for this purpose was password-protected to prevent any risk of data leakage. In the event of equipment loss, all study information could be remotely deleted. After the study teams finished their daily tasks, the smartphones were synchronised with a password-protected server. Access to the data was restricted to authorised personnel only.

Study variables

The dependent variables were the ability to pay for VMMC and the willingness to pay for VMMC. The main independent variables were income, beliefs, knowledge, attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behaviour control about VMMC. Other independent variables (control variables) were the respondents’ social demographic descriptors.

Data analysis

Ordinary least squares regression was employed to evaluate the ability to pay for voluntary medical male circumcision. In contrast, willingness to pay—measured as a dichotomous outcome—was analysed via logistic regression. Two models were developed for both dependent variables. Model 1 included only control variables (social demographic descriptors) as independent variables, whereas Model 2 incorporated control variables and the factors under investigation. Correlational analysis was conducted to assess the strength and direction of the linear relationships between the variables. The variance inflation factor was also utilised to assess multicollinearity among the variables.

Qualitative data were analysed using the reflexive thematic method.20 The qualitative component was part of a larger study.21 Reflexive thematic data analysis was performed using NVivo ® version 12 (March 2020).22 Data collection and analysis were iterative; researchers listened to recordings to identify topics in interviews. Transcripts were reviewed multiple times before and after importing into QSR NVivo ® to familiarise ourselves with the data. The first reading was open-minded, allowing for an appreciation of the richness of the data. In the second segment, relevant aspects of the study were highlighted, including language and emotions such as laughter.

Coding was both manual and electronic, utilising QSR NVivo, to generate initial codes. Common data patterns addressing the research question were highlighted with different colours. The process involved identifying deeper meanings and ensuring no codes were missed, with each unit coded under only one category. The initial codes reflected basic data for evaluation, and coding continued until no new codes emerged.

The next phase narrowed the analysis to higher-level categories and sub-themes by combining related codes, with memos recording the process. The validity and reliability of interpretations were ensured by including respondent quotes under the appropriate subthemes. Iterative sorting generated descriptive themes while allowing for the emergence of new codes and themes. This thematic revision involved consolidating, separating, transforming, and removing vague codes.

After creating descriptive sub-themes, the analysis defined the meaning of each sub-theme to develop analytical themes, combining or splitting sub-themes as needed for accuracy. Analytical themes were named succinctly for clarity.

The final phase involved drafting a report of the study’s results, presented in narratives. Direct quotes from interviews were included, preserving grammatical errors to reflect the responses accurately. Where abbreviations appeared, the full term is indicated in square brackets, with keywords represented by articles like "it, " "this, " and “them” shown in square brackets.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents

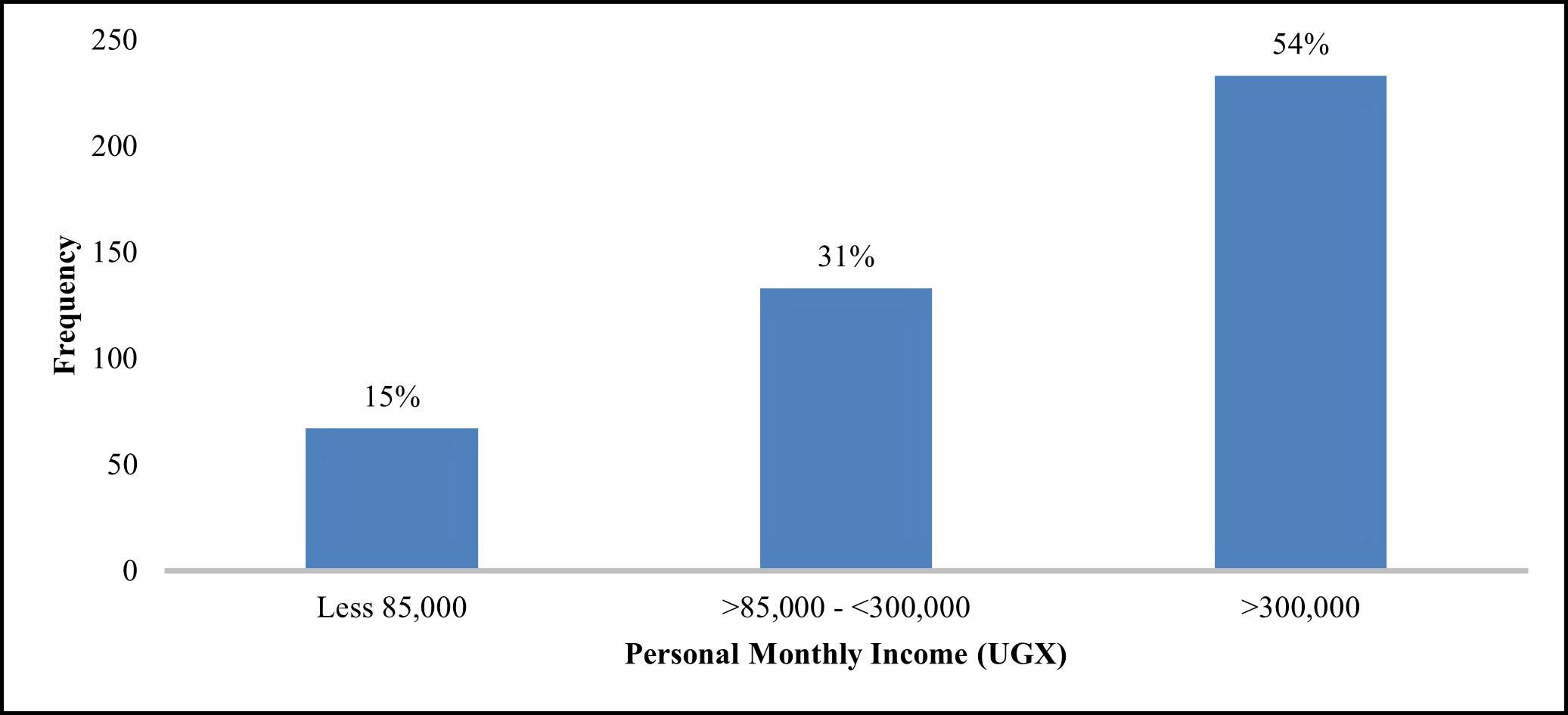

Table 1 illustrates the sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents who participated in the quantitative study. A total of 454 respondents, with an average age of 43 years, were enrolled in the research. The majority were married (90%), identified as Christians (85%), had at least a secondary school education (61%), and were self-employed (80%). Slightly more than half (54%) of the respondents lived in rural areas. Personal monthly income varied from zero to eight million Uganda shillings (UGX) (approximately $2160), with an average of UGX 435,636 ($117.6).

Ability to pay for VMMC

Personal monthly income was utilised to assess individuals’ ability to pay. The first, second, and third quintiles of personal revenue were established by creating a new variable based on the percentiles of personal income. The mean incomes for these quintiles were UGX83,900 ($22.7), UGX285,300 ($77), and UGX1,058,900 ($286) for the first, second, and third quintiles, respectively. Considering that the average cost of VMMC is UGXUGX100,000 ($27), it was assumed that individuals in both the second and third quintiles could afford to pay for VMMC. Fig. 1 illustrates the respondents’ personal monthly income, revealing that a significant majority (85%) earned more than UGX85,000 ($23).

Factors that determine the ability to pay for VMMC

The study’s first objective was to identify the factors determining the ability to pay for voluntary medical male circumcision in Uganda. An ordinary regression test was conducted to achieve the first study objective, and the findings are presented in Table 2.

The Model 1 column outlines the dependent variable alongside the control variables, whereas the Model 2 column incorporates the variables of interest into the independent variable. In Model 1, age showed a positive relationship with the ability to pay for circumcision, suggesting that as age increases, the ability to pay for circumcision increases by UGX10,595 ($2.90). Compared with Christianity, which served as the reference group, individuals with no religious affiliation demonstrated a significantly greater ability to pay for circumcision. Furthermore, those holding a degree or diploma exhibited a greater ability to pay for circumcision, estimated at approximately UGX527,852 ($142.50), than individuals with other educational levels.

Individuals lacking formal education exhibit a negative correlation with ATP, suggesting a reduced ability to pay compared to their college-educated counterparts, with a difference of UGX745,503 ($201.3). Compared with college attendees, those with primary and secondary education also demonstrated a decrease in their ability to pay. However, this decline was less pronounced than that of individuals without any formal education.

The residential environment in which an individual lives is crucial in determining their ability to pay. The findings show that those residing in rural areas had a significantly lower ability to pay than their urban counterparts, with a difference of UGX323,503 ($87.3). Additionally, perceived behavioural control negatively affected the ability to pay, as a unit increase in PBC resulted in a decrease in the ability to pay for circumcision by UGX44,785 ($12.1).

Willingness to pay for VMMC

The study revealed that most (76%) were willing to pay for VMMC. The respondents who reported a willingness to pay for VMMC were further asked to state the maximum amount they would pay while considering their other financial obligations. The findings are shown in Fig. 2. A negatively sloped demand curve was revealed, with the number of people willing to pay diminishing drastically as the price increased. Most respondents (326/371, 88%) were willing to pay less than UGX100,000 ($27).

Enablers of Willingness to Pay for VMMC among Study Participants

The logit regression model was used to assess the willingness to pay for VMMCs in Uganda. The log-likelihood value (–226.0049) showed that the model converged quickly. The likelihood ratio chi-square and p-value of 38.52 and 0.0001, respectively, revealed that the model fit significantly better than a model with no predictors.

Model 1 in Table 3 presents the initial regression analysis, which included only the control variables as independent variables. The results indicated that one specific variable—identifying as a Muslim rather than a Christian—increased the willingness to pay by 1.45. Model 2 in Table 3 adds the variables of interest to those control variables utilised in Model 1. The findings demonstrate that being a Muslim contributes to a 0.96 increase in the willingness to pay. Furthermore, knowledge shows a significant positive correlation with a willingness to pay; for each unit increase in knowledge, the log odds of willingness to pay for circumcision versus unwillingness to pay increase by 0.09.

Findings from the in-depth interviews revealed several factors influencing people’s willingness to pay for VMMC. Among them were the following.

Some respondents viewed paying for circumcision as an investment to minimise future expenses since VMMC is performed for disease prevention.

“I believe that prevention is better than a cure, so paying is not a problem” (31 years old, single, diploma holder, rural resident).

“The other thing, paying is not the problem because they might ask you for fifty thousand and you say that the money is a lot, but in future, it costs you much more than what you would have paid” (20 years old, single, tertiary education, peri urban resident).

“As a man, when you are not circumcised, it is not good because sometimes you get infections, and you keep spending a lot of money to treat those infections, so [if] I can get the money, like maybe UGX50,000 ($13.5), and go to the hospital for a circumcision” (28 years old, married, uneducated, urban resident).

A few other respondents believed that paying for VMMC was normal, similar to other medical expenses that must be incurred; therefore, paying for VMMC should be viewed from the same perspective.

“It is just like paying for other services in the hospital, and I think if I was not circumcised, maybe I would have contracted other diseases like candida, and so I would pay for my children” (21 years old, single, university education, rural resident).

"In the end, it is beneficial to your health, so [it is] something that is going to help you, and the cost is not high for someone to afford; it is not bad" (19 years old, single, S.6 urban resident).

“So, aren’t there individuals who suffer from malaria and go for private services where they pay? Therefore, it should also be considered like any other sickness, and any willing person can access the services, so you just find out the cost. For example, if it’s like UGX30,000 ($8.1), then the medicine to buy could be UGX20,000 ($5.4). Save your UGX50,000 ($13.5) and [use it to] receive the service” (37 years old, single, certificate holder, urban resident).

The association of free services with poor quality services and paid services with better quality services was a significant factor influencing the willingness to pay for VMMC. Some respondents perceived free VMMC services as lacking in quality because of the high volume of patients, which could lead to compromised care. Others believed that private clinics employ superior experts compared with those available in VMMC camps.

“I don’t want things of many people because I fear getting infections from there and. . . that’s why I decided to go and pay” (18 years old, single, S.4, urban resident).

“Free things are very expensive because there are things behind the scenes that you people don’t see, and they can’t even tell them to you [laughs]. I believe in getting an expert to do it for you in a [private] clinic or drug shop, and then they give you medicine, which you pay for. Things for free are not easy, and that is the truth [laughs]” (26 years old, single, diploma, urban resident).

The attitudes and beliefs of individuals about the benefits of VMMC play a significant role in their willingness to pay for the procedure. Those who held a positive view of VMMC were more inclined to pay than those who did not share this perspective. Numerous voices expressed favourable attitudes that ultimately influenced their decision to pay.

“Yes, I would be willing to pay because, besides the cultural bit, it keeps the man clean, but having a foreskin makes one unhygienic, so I would pay for it if it was for paying, and that is for the hygiene” (28 years old, single, S.4, peri urban resident).

“I would be saving my life. I am not saying that one who is not circumcised doesn’t get infected, but the chances become limited when you are circumcised” (27 years old, married, uneducated, peri urban resident).

“As a person, if I have the money, I can pay because of the benefits of circumcision that I know” (31 years old, single, diploma, rural resident).

“I am willing to pay for it because I have seen the benefits of circumcision from my friends” (22 years old, separated; S.4, rural resident).

The benefits of VMMC in influencing the willingness to pay are strengthened by positive lived experiences. One respondent, who was already circumcised, shared his personal experience:

“I know the advantages of circumcision and am willing to pay for my children. Personally, I am already circumcised, and it was free of charge…., but if the service is no longer free, I can pay for my children at any cost because of the advantages and the knowledge I have about the practice” (31 years old, married, certificate, rural resident).

Barriers to Willingness to Pay for VMMC among Study Participants

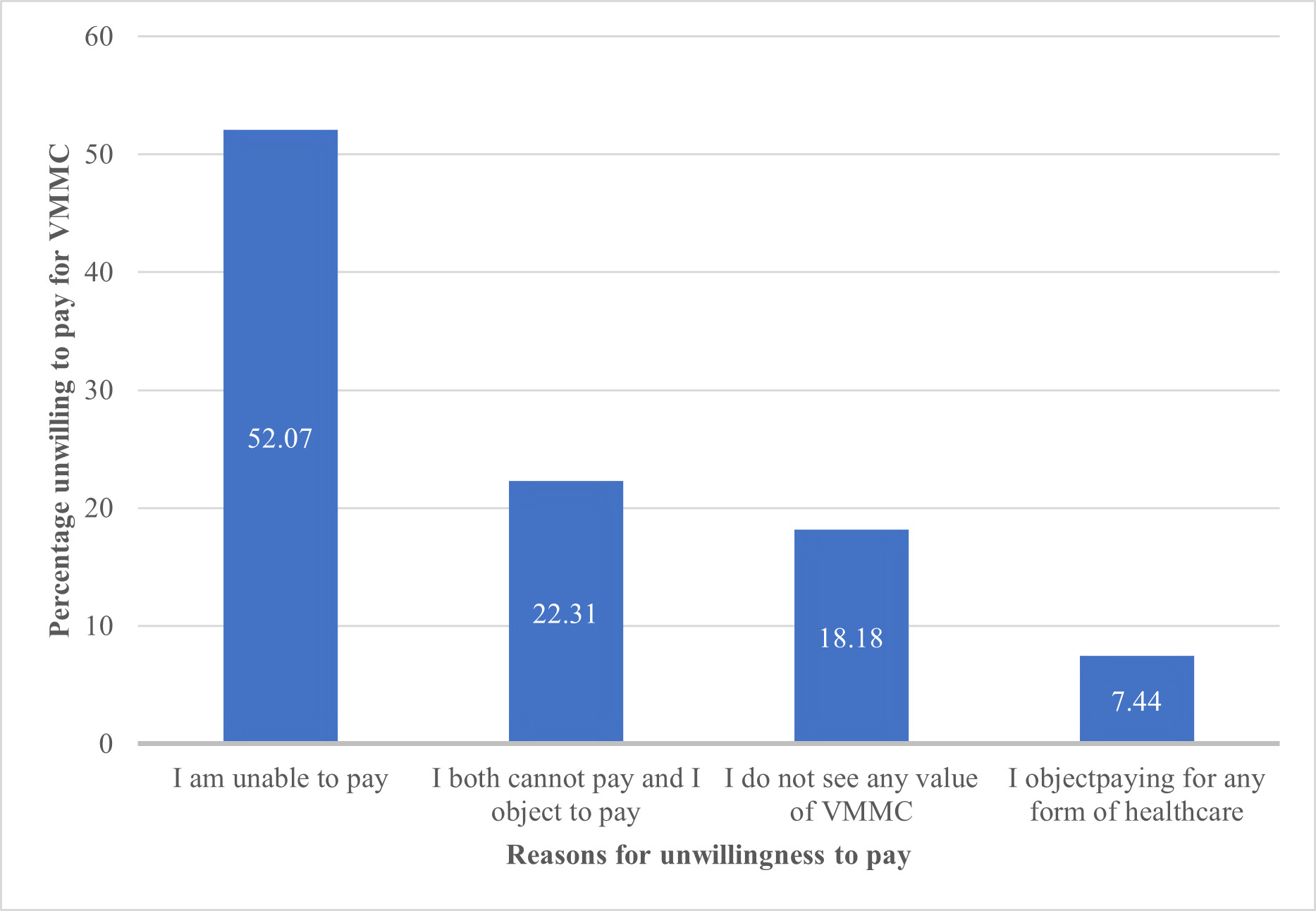

Twenty-four per cent of the respondents in the quantitative study reported being unwilling to pay for VMMC. They were given various options to express their position. The findings are displayed in Fig. 3, indicating that the majority (52.1%) cannot pay.

According to Table 3, two factors negatively impact the willingness to pay for voluntary medical male circumcision. Males without formal education demonstrate a 1.38 times lower likelihood of being willing to pay for circumcision than those with tertiary education. Additionally, living in rural areas, as opposed to urban settings, is associated with a significantly reduced willingness to pay for circumcision, with a decrease factor of 0.74.

Model 2 in Table 3 includes the variables of interest alongside the control variables utilised in Model 1. All significant variables from Model 1, namely, no formal education and rural residence, continue to show significance, albeit with a reduction in coefficient sizes. The results indicate that perceived behavioural control is inversely related to the willingness to pay for VMMC. Specifically, for each unit increase in perceived behavioural control, the log odds of being willing to pay for circumcision as opposed to being unwilling to pay decrease by 0.26. Furthermore, the findings suggest that the attitudes, subjective norms, and beliefs of males do not have a significant effect on their willingness to pay for circumcision.

The in-depth interviews revealed some factors that diminish the willingness to pay for VMMC, including the following.

The cost of VMMC is a significant factor in determining willingness to pay for it. Some respondents were willing to pay for VMMC if the price was reasonable and affordable. Several proposals and suggestions have been made that are considered reasonable. Other respondents are willing to pay for VMMC as long as the cost includes all necessary postoperative care.

“Five thousand or UGX10,000 ($2.7) is affordable” (35 years old, married, certificate holder, rural resident).

“I agree with paying for the service as long as it’s affordable; it’s very okay” (20 years old, single, tertiary education, peri urban resident).

“If the money is high, like UGX100,000 ($27), I will keep postponing it, and I [might] end up not even doing it” (31 years old, single, diploma holder, rural resident).

“If the whole cost goes for UGX20,000 ($5.4), plus drugs and bandages, then people could be willing to pay for it” (21 years old, single, university, rural resident).

Voluntary medical male circumcision comes with an opportunity cost that some respondents are reluctant to accept. Due to prevailing economic hardships, they did not view it as a priority. The respondents expressed their feelings about VMMC being a lower priority.

“It should remain free because some people don’t have money (laughing)” (39 years old, single, primary 7, urban resident).

“I do not believe in people paying for the service; I object to that. Because we are in a third-world country and people cannot afford medical services, I think if they cannot afford to treat themselves for malaria, how will they afford to pay for circumcision? It should continue to be a free service” (25 years old, single, tertiary education, urban resident).

“I think that there are people who cannot afford it, so the person looks at putting money in circumcision, yet even if they are not circumcised, they will be alive, so I can’t pay because, if at the moment I don’t have money for posho [maize meal], and then I think of getting money to go and pay for circumcision yet, even if I am not circumcised, I will remain alive, so I see that it will not work” (27 years old, married, uneducated, preurban resident).

Some respondents felt a sense of entitlement and believed that voluntary medical male circumcision should be provided free of charge, as it is viewed as a public good. They suggested that VMMC should be integrated into public health services and plans, similar to the treatment of other medical conditions, ensuring that anyone in need of circumcision can access the service at their nearest health facility. One respondent expressed concern that charging for VMMC could negatively impact demand for the service.

“If health experts confirm that it does contribute to the prevention of HIV, then it should be a free service. And it should be in the national plan to eradicate the spread of HIV in the country” (32 years old, single, university, urban resident).

“I think that it [asking people to pay] will reduce the number of people who are getting circumcised because right now it is free, but you just have to encourage people to go, so if you put money, people will say that they don’t have money, and they will use it as an excuse not to go, but when it is free, it is easier to convince someone to go for it” (27 years old, married, uneducated, peri urban resident).

One critical factor undermining the willingness to pay for VMMC is financial ability. Numerous respondents shared compelling stories that revealed how they struggled to afford VMMC because of a lack of stable income. Many articulated the pressure of being their family’s sole breadwinners, relying on daily earnings to meet basic needs, and voiced their deep concerns about how their families would endure without their support. Investing in VMMC is not just a personal choice; it is a question of survival for many families.

“Most of us depend on the daily wage” (37 years old, single, certificate, urban resident).

“I like that thing [circumcision], but I fear that if I do it, I will not be able to work and provide for my family, and they might die of hunger” (28 years old, married, uneducated, urban resident).

“I am a volunteer and have to work every day. I don’t get leave, and if I don’t work, I cannot get that little allowance I get when I work daily” (31 years old, single diploma, rural resident).

A key factor affecting people’s views on paying for VMMC is the potential cost of post circumcision care. Clients often worry about their recovery and the financial implications of possible complications. While many can afford the procedure itself, uncertainty about postsurgical expenses was a concern. The respondents emphasised the importance of being well-prepared for VMMC, including saving funds for any potential issues that may arise.

“The other thing is that they might circumcise you, and they don’t give you the treatment you need” (28 years old, single, senior 4, peri urban resident).

“Yes, I worry that we react differently. When someone is circumcised, some people’s bodies take longer to heal, so the expense of treating the wound, the burden is on the client and the parents, yet sometimes getting money for nursing the wound for low-income earners may be difficult, especially in this economy of low developing countries like Uganda, where most things are expensive more, especially the drugs with prices that keep going high, so it leaves us in fear. I worry that the free service should never come with a cost because, in most cases, the service is free, but the effect is for payment” (31 years old, married, certificate, rural resident).

Equity in the provision of VMMC services is a vital consideration when implementing a fee-for-service VMMC. The respondents believed that not everyone should be required to pay and that certain groups should be exempt from paying. This is not only due to the unfairness of imposing costs on them, but also because they may struggle to afford the expense.

“Some people cannot afford to pay for it, so they should separate those who can and cannot. Some people are down in communities with very little or no income to afford, but there are those who have their money and can pay. So, those who cannot pay should call them for free services” (38 years old, single, senior 1, urban resident).

Some respondents expressed concern that charging for VMMC could lead to corruption and delays in service delivery; thus, it is preferable to keep it as a free service.

“When they attach a cost, you might find that there is a certain figure they have determined, like maybe UGX5,000 ($1.4) or UGX10,000 ($2.7). Still, in some facilities, you might find some health workers inflating the costs and even asking for bribes from clients like UGX20,000 ($5.4) to be able to receive a faster service than others, but when the service is free, even the health worker knows that all people have to be handled the same because the service is free, so bringing in the issue of paying may cause unfairness that, even if I was the first at the hospital, the one who gave them a bribe will be worked on and leave me there. I will probably even go back home without receiving the service” (19-year-old, single, senior 6, urban resident).

DISCUSSION

This study evaluated the ability and willingness to pay for voluntary medical male circumcision as an option for reducing reliance on external funds for HIV prevention initiatives in Uganda. The results revealed that 85% of the respondents had a monthly income of at least UGX 85,000 ($23), enough to cover the average cost of VMMC, which is UGX 81,400 ($22). Additionally, 76% expressed a willingness to pay for VMMC, with 88% of those interested preferring to contribute less than UGX 100,000 ($27).

While out-of-pocket (OOO) payments may be regressive and unappealing due to the contradiction with the principles of universal health coverage and the potential to generate less funding than external donations, they represent a viable approach to enhancing domestic resources for HIV prevention in low- and middle-income countries. This is particularly relevant in contexts where alternative methods of healthcare resource mobilisation, such as taxation, social health insurance, and private sector funding, face significant challenges.23 Payment at sources for HIV services is not new. It has been used to access several HIV services that include ART, HIV testing services, and prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV across several countries in Africa.9

HIV and AIDS services in Uganda, including VMMC, are funded primarily by external donors, notably PEPFAR and the GFATM.5 External funding must be replaced with other domestic sources to sustain these services. Recognising the constraints of the present domestic budget, more than financing via taxes may be needed. Proposals have been made for suspending debt repayment or relief from debt repayment as an alternative to freeing up domestic resources that can be channelled to HIV and AIDS responses.4 However, with the generally underfunded health sector,24 there is no guarantee that money earmarked for debt repayment will be specifically allocated to HIV and AIDS responses. Payment at the source offers an opportunity to ring-fence resources for HIV prevention.

Our study reveals that many individuals are able to pay for VMMC without facing financial difficulties, as it is a one-time, lifelong intervention. However, not everyone in need is able or willing to pay for it. The factors positively associated with the ability to pay include increasing age, a lack of religious affiliation, and higher levels of education. In contrast, residing in rural areas, having limited education, being self-employed, and having high perceived behavioural control can reduce this ability. The interviews indicated that the cost of VMMC is a significant barrier to access. There have been a few recent studies on the ability to afford healthcare. Most of the literature focuses on WTP. Our findings underscore the significant role of socioeconomic status in determining the affordability of healthcare. Therefore, any attempt to introduce a fee-for-service VMMC should consider these factors to ensure that HIV prevention services remain equitable and that individuals seeking services do not face financial hardships.

Factors such as the ability to pay, knowledge about voluntary medical male circumcision, and identification with the Islamic faith positively influence the willingness to pay for VMMC. On the other hand, a lack of education, living in rural areas, and high perceived behavioural control negatively impact this willingness. Our findings are consistent with those of previous studies.25 This research provides important insights into implementing fee-for-service VMMC. For example, the program could focus on urban working men while offering free services to those in rural areas.

The in-depth interviews revealed mixed findings. The respondents who expressed a willingness to pay for VMMC provided several reasons for doing so. These included VMMC being viewed as an investment in one’s health, an obligation similar to any other health matter, fear of poor-quality services from free services, and a generally positive attitude towards male circumcision. These findings underscore the importance of delivering people-centred services to boost demand. On the other hand, people who are unwilling to pay for VMMC, among other reasons, cite the following factors as influencing their decision: VMMC is a public good that should be provided at no cost to the recipient, the prevailing challenging economic situation, the high opportunity cost associated with paying for VMMC, a feeling of entitlement to free public health services, the need for equity, and the affordability of VMMC. The findings indicate that the cost of healthcare remains a consideration when seeking services. Financial protection services should be available to those in need who are unable to afford healthcare.

Our findings stand in contrast to those from Western Kenya, where a significant proportion of households (62.2%) had the ability to pay, yet only 40% expressed a willingness to pay for VMMC.13 This discrepancy may be attributed to the fact that the Kenya study included household heads, some of whom were female. In contrast, our study focused solely on adult males as respondents. Given the private nature of adult male circumcision, individuals may derive more personal value from circumcision than households do collectively. Additionally, income and the prevailing economic situation influence the willingness-to-pay (WTP) for healthcare. It is possible that the prevailing economic conditions in Kenya could have influenced WTP decisions.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions in place at that time, we collected data from participants sourced from a database maintained by a research organisation. Our analysis indicates that the study population largely reflects the general population, with the only notable differences being average income and education levels.

Like the general population, the study participants were predominantly Christians, married or cohabiting individuals, included a significant number of self-employed persons, and consisted mainly of rural residents. The average income of our respondents was UGX250,000 ($67.5), which is lower than the average income of the general population at UGX435,656 ($117.6).26 Furthermore, 55% of our respondents had primary-level education, compared with 41% in the general population.26 This suggests that our study population had lower income and education levels, which we believe enhances the significance of our findings in the context of a willingness-to-pay (WTP) study, compared to a study population with higher income and education levels.

The strength of our study resides in its application of mixed methods to examine the willingness to pay. Prior to this research, the only existing study on willingness to pay for VMMC13 utilised a quantitative approach, leaving several unanswered questions about the factors influencing these payment decisions. The current research bridges the gap in the literature by employing a mixed-methods design, underpinned by the application of explicit theories to identify study variables.

Another notable strength of the current research is its focus on adult males, unlike previous studies on VMMC payments, which focused primarily on household heads.13 Whereas households are key in determining household expenditures.27 Given the private nature of adult male circumcision,28 payments for VMMC may not be a significant topic at the household level, especially given the high opportunity costs. However, if adult males perceive value in VMMC, they may be willing to pay despite the cost.

Additionally, this research distinguishes between the ability to pay for a health service and willingness to pay, a nuance often overlooked in earlier studies.

Our study had limitations. In addition to the general limitations of contingent valuation studies,29 our study has another limitation: virtual data collection. Due to ongoing COVID-19 restrictions, the study was conducted with respondents recruited from an existing database, and data were collected virtually through phone interviews. Accessing participants by phone may have introduced bias into the study population, positively favouring those with the ability and willingness to pay. This circumstance could indicate a higher socioeconomic status than the general population.

CONCLUSION

We confirm the ability and willingness to pay for VMMC to reduce reliance on external support for VMMC services in Uganda. The cost of VMMC is critical in influencing individuals’ willingness to pay for the procedure. We recommend that the introductory fully loaded fee for VMMC not exceed UGX100,000 ($27). To be effective, any proposed fee should perhaps be inclusive of the costs associated with the surgical procedure itself, as well as any necessary postoperative care. While VMMC is typically a one-time service and unlikely to cause financial hardship, establishing a payment structure that accommodates each individual’s ability to pay is important. The pricing for VMMC should be carefully determined, and the prevailing economic conditions in the target geography should be considered to reflect the financial abilities of individuals. We call upon the Ministry of Health to consider introducing fee-for-service VMMC for those who are able and willing to pay.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval to conduct this study was obtained from the Faculty of Health and Medicine Research Ethics Committee at the University of Lancaster (Approval number: FHMREC20119) and from Mildmay Uganda (Approval number: MUREC-2021-50). This study was registered and cleared to be conducted in Uganda by the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (Registration number HS1523ES). Informed consent was obtained from all the participants before participating in the study. All study procedures were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki..

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Funding

This study did not receive any external funding.

Authorship contributions

JBB conceived, designed, and implemented the study; ML and BH contributed to design, supervision, and manuscript revision. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure of interest

The authors completed the ICMJE Disclosure of Interest Form and disclose no relevant interests.

Correspondence to

Bailrigg, Lancaster LA1 4YW, United Kingdom

jbyabagambi@gmail.com

_for_vmmc.png)

_for_vmmc.png)