INTRODUCTION

Infertility is generally defined as the failure to achieve a pregnancy after 12 months (or 6 months if the woman is over 35) of regular, unprotected sexual intercourse.1 It is a global health issue with a lifetime prevalence of 18% and a period prevalence of 13%.1,2 Infertility can be primary or secondary. Primary infertility is when a pregnancy has never been achieved by a person, and secondary infertility is when at least one prior pregnancy has been achieved.3,4 The global prevalence of primary infertility is 1.8% for males and 3.7% for females.5 There are regional and population-specific differences in these prevalence rates, with higher rates observed in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).1,2 Possible reasons include socially rooted misconceptions, such as that infertility is a woman’s issue, lack of awareness, affordability, and limited access to infertility care services such as Assisted Reproductive Techniques (ART).6,7 Despite recent advancements in infertility treatment, significant disparities persist in access to care, particularly in South Asian and African LMICs, where the availability of services is limited.8,9 There are also disparities within countries, with infertility care ranging from basic diagnostic services to ART availability.10,11

Infertility is a biological outcome, and it has socio-cultural consequences for both partners; women disproportionately bear the blame.12 Its negative sociocultural impacts often lead to intimate partner violence, mental health issues, and divorce. Infertility is also linked to stigma that often stems from societal beliefs equating a woman’s worth with her ability to have children. This leads to derogatory labels such as “barren” or “incomplete” and results in social exclusion, blame, and discrimination from both family and the broader community.6,13–15

Bangladesh is a high-fertility country in South Asia that recognized population growth as the primary development challenge in the 1970s.16 Since then, reducing fertility has been the priority of the national population programs.17 It left the issues of infertility unaddressed, and nearly 4% of couples experiencing primary infertility remained invisible.18–20 Moreover, recent evidence shows an increase in infertility rates in the country; during 2000 and 2018, the prevalence of primary infertility rose from 1.8% to 2.4%.21 The increase highlights the necessity of tackling infertility as a new public health priority in the country.

The challenges faced by infertile couples in Bangladesh are intensified by the cultural expectation of parenthood, which places immense pressure on couples to conceive.22,23 Infertility is stigmatized in this country and viewed as a personal failure.23 These socially rooted beliefs influence delayed or inappropriate care-seeking decisions.24 Additionally, gender norms play a significant role, as women are often regarded as bearing the primary responsibility for infertility.6 The contextual burden of infertility weighs more heavily on women in rural areas where traditional values, perceptions, and norms are strongly prevalent.25 And, the challenges related to infertility are most often attributed to primary infertility.

A few studies on infertility care in Bangladesh have been conducted; most are over a decade old.20,23–25 Studies examining stakeholder perspectives and conducting policy analysis highlighted a lack of government commitment to infertility care, primarily because existing programs concentrate on lowering fertility rates.20 Regarding individual care-seeking, several studies based in single facilities have indicated a reliance on traditional healers, low utilization of ART care, and high treatment dropout rates, primarily due to high out-of-pocket expenses.26–28 Only one ethnographic study examined health-seeking behavior at the community level and discussed the impact of sociocultural factors on the locations and choices of treatment.24 This means that infertility policies and programs are formulated based on insufficient research and a poor understanding of the dynamics of infertility care within a complex sociocultural context.20,27,29 Furthermore, the absence of a thorough assessment of the availability of infertility services and the related structural challenges across various healthcare tiers further complicates the development of infertility care strategies and action plans.9,20,27 In light of the previously mentioned context, this study explores various aspects of primary infertility care in Bangladesh. The specific objectives of the study are to examine:

-

The care-seeking behavior and experience of the primary infertile women (PIW). (The PIW often refers to primary infertile couples at different places in this paper);

-

The infertility care availability at different healthcare tiers, and

-

The challenges and opportunities in the provision of infertility care

METHODS

STUDY DESIGN

We implemented an explanatory sequential mixed-methods study design that included a population-based cross-sectional survey followed by a qualitative study.

STUDY SITE

The survey was conducted at two Health and Demographic Surveillance System (HDSS) sites: Matlab HDSS and Baliakandi HDSS, managed by the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b).

Matlab HDSS: icddr,b has been implementing the Matlab HDSS since 1966, covering approximately 250,000 people in 2022, residing in about 63,000 households across 142 villages in rural Chattogram. The HDSS records demographic events and gathers selected reproductive, maternal, and child health information by female data collectors who visit households on a three-month cycle. During these visits, the data collectors ask all married menstruating women whether they missed their last menstruation. Women who missed their previous menstruation and have not taken a pregnancy test are offered an on-the-spot pregnancy test. Consequently, the HDSS provides reliable data on pregnancy.

Baliakandi HDSS: The Baliakandi HDSS, also maintained by icddr,b, is situated in the Baliakandi sub-district of the Rajbari district within the Dhaka division. In 2022, it covered approximately 226,000 rural residents living in about 57,000 households across 261 villages. The HDSS records demographic events and gathers selected health and socioeconomic data through household visits, similar to the Matlab HDSS.

SAMPLING, SAMPLE SIZE, STUDY PARTICIPANTS, AND FIELDWORK

Survey: We employed an age-stratified random sampling design, focusing on women aged 20-34 and 35-49 years across the two HDSS sites. Both age-specific stratification is biologically focused, as the 20–34 age range captures the prime reproductive years, where early signs of infertility may emerge and care-seeking behaviors begin. The 35–49 age group represents women closer to the end of their reproductive age, who have experienced a prolonged history of infertility. The age-stratification created the scope of age-specific analysis by capturing sufficient cases in different age. Nearly half of the women below 20 remain unmarried (or out of cohabitation), so we excluded them. Pregnancy and childbearing beyond wedlock are not socially accepted in Bangladesh, and are extremely rare.

The Matlab and Baliakandi HDSSs provided a list of currently married women aged 20-49, along with their pregnancy status (whether they had ever conceived—yes or no). This list served as the sampling frame, from which we oversampled women who had never conceived within each stratum. Within each stratum, participants were selected using simple random sampling. The sample size was established to estimate the prevalence of primary infertility, based on existing literature indicating a prevalence rate of 2%. We utilized Cochran’s formula, incorporating a 95% confidence interval (95% CI) and an allowable error of 1%, while also accounting for stratification by age groups (20-34 years and 35-49 years) and by location (Baliakandi and Matlab). This resulted in a required sample size of 3,312, which we rounded up to 3,400. It also included a 10% non-response rate in our calculations. Furthermore, we allowed for oversampling of women who had never been pregnant to secure the necessary sample for the cohort follow-up and to evaluate changes in fertility status and service utilization over time with statistical precision. The survey was conducted between October and December 2022, during which we interviewed 2,948 women, achieving an 88.5% response rate. Among them, 238 were identified as Primary Infertility Women (PIW). The process for identifying PIW is detailed in the following section, “PIW identification.” The survey provides data to address questions related to care-seeking and care-receiving.

In-depth interview (IDI): We also conducted IDIs with purposively selected 10 PIWs and their husbands (5 from each HDSS site) from February to May 2023. The IDIs with husbands and wives were conducted separately by male and female anthropologists, respectively. Participants were selected from different age groups, education levels, and religious backgrounds, with varying marriage durations. This diversity was expected to help us document care-seeking behavior and social experiences related to infertility among couples from various socio-demographic backgrounds. The IDIs examined couples’ perceptions of infertility, its impact on social, marital, and psychological well-being, and their care-seeking experiences. However, this paper focuses solely on care-seeking experiences to complement the survey findings.

Key informant interview (KII): We conducted eight KIIs from March to May 2023, which included discussions with six esteemed infertility specialists, representing the nation’s only professional Society on Fertility and Sterility, as well as specialists from large public and private infertility centers. Additionally, we conducted two KIIs with gynecology consultants who operate private practices in Baliakandi and Matlab. Initially, a nationally renowned infertility care specialist was purposively selected for the interview. The subsequent participants were selected based on recommendations from the previous participants, employing a snowball technique. The key informants discussed the care that infertile couples require, the care available at various tiers of public health facilities and private practices in Bangladesh, as well as the challenges associated with infertility care in the country, including both supply-side and demand-side, and other related matters.

In this study, the quantitative survey helped us to identify the care-seeking patterns and service gaps. The IDIs and KIIs provided context-rich explanations of those patterns. The qualitative data helped interpret the reasons behind the quantitative survey findings, such as preferences for traditional healers, decision-making dynamics, or treatment discontinuation. This mixed-method design has ensured an understanding of the factors influencing infertility care, challenges, and opportunities in a holistic view.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Written informed consent was obtained from all questionnaire interview, IDI, and KII participants. Interviewers received training on how to approach infertility-related topics in a respectful and empathetic manner. All interviews were conducted privately, and participants were informed of their right to withdraw at any time. Confidentiality and anonymity were maintained throughout the data collection, analysis, and reporting process. The study received approval from the Institutional Review Board of icddr,b.

PIW IDENTIFICATION

We identified the potential PIW using a modified version of the demographic definition of primary infertility. According to the demographic definition, a woman is presumed to PIW if she fulfills the following four criteria: 1) never had a live birth, 2) in union for the past five years, 3) had regular unprotected sexual intercourse, and 4) had a desire for a child.30

Demographic definition employs ‘live birth’ as an outcome due to the challenges associated with obtaining conception history through community-based data collection. However, previous studies have argued that “conception” may be a more accurate outcome measure to determine primary infertility.30,31 Therefore, we replaced “live birth” with “conception” in Criteria 1. We defined union as ‘currently married’ in Criteria 2, considering the context of Bangladesh, where the socio-religious culture accepts sexual union only within marriage. We did not collect any direct information on regular unprotected sexual intercourse. Therefore, we considered “currently living with husband (husband visited at least once in the past year if he is not currently living with)” as a proxy for “regular unprotected sexual intercourse” in Criteria 3.

Thus, the PIW identification in this study used the following four criteria: 1) never conceived, 2) married for at least five years, 3) currently living with husband (husband visited at least once in the past year if he is not currently living with the woman), and 4) had a desire for a child. We excluded women who had had a hysterectomy.

DATA ANALYSES

Study participant: We presented the socio-demographic characteristics of the survey respondents and PIW using numbers and percentages. We also showed the number of IDI participants by socio-demographic and KII participants by health center types.

Objective 1. Care-seeking experience: We examined whether the PIW ever sought care for infertility, where they sought care, whether they underwent any medical tests, and other related data (e.g., who recommended visiting healthcare facilities, satisfaction levels with infertility treatment, types of treatments received, who initiated the care-seeking process, etc.). Due to the age stratification in the sampling technique and the oversampling of women who never conceived, the age distribution of the 238 PIW in the sample differed from that of women who never conceived in the population. Therefore, we used survey weights for data analysis. The results are presented in numbers and percentages. Given the high level of care-seeking, we did not conduct any descriptive or multivariate analysis to examine socio-demographic correlates.

Guided by the survey findings, the qualitative exploration concentrated on four broad themes: knowledge and perceptions of infertility, motivation for seeking care, decision-making related to care-seeking, and experiences with obtaining care. For the KII analysis, thematic analysis with open coding was used to systematically assess the challenges in infertility service provision in Bangladesh. The analysis began with familiarizing with the data, followed by organizing the data into tables to create a matrix. Framework analysis was then applied using these matrices to uncover emerging patterns, examine commonalities, and identify differences within the data. Throughout the research process, methods such as cross-checking variables, triangulating various data sources, and assessing saturation were employed to enhance the reliability and validity of the findings.

Objective 2. Availability of infertility care: The key informants provided a list of diagnostics and treatments that should be available in infertility care. They identified specific facilities where these services were offered. We summarized the essential services for infertility care and their availability by type of facility (primary, secondary, and tertiary/specialized).

Objective 3. Challenges and opportunities in infertility care: We performed a thematic analysis of the KIIs to identify the existing challenges and opportunities related to infertility care. During our discussion, the key informants highlighted immediate policy actions necessary for improving infertility care. Additionally, we conducted a thematic analysis to summarize the policy actions suggested by the key informants.

RESULTS

BACKGROUND CHARACTERISTICS OF THE STUDY PARTICIPANTS

Table 1 presents the background characteristics of the study participants, including those of survey respondents, PIW, IDI, and KII participants. The highest and lowest proportions of women were 25-29 years (20%) and 45-49 years (11%), respectively. A substantial proportion (42%) of the women were married before age 18, and 89% of the respondents had been married for five years or more. Over a quarter (28%) of the participants had completed secondary education or higher. The majority of the women (85%) identified as Muslim. Table 1 also displays 238 PIW by background characteristics. Based on their background characteristics, we found that the 238 PIW were comparable to the overall study sample.

ID respondents: Among the ten couples selected for IDIs, the husbands’ ages ranged from 32 to 67 years, while the wives’ ages ranged from 20 to 40 years. Most couples were Muslim and had been married for seven years or more. The spousal age gap varied from 7 to 13 years. Nearly half of the couples had some secondary education. (Table 1).

OBJECTIVE 1: CARE-SEEKING BEHAVIOR AND EXPERIENCES

CARE-SEEKING

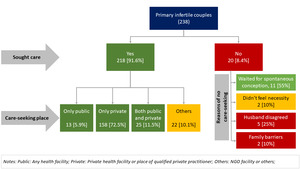

Ninety-two percent of the PIW ever sought care. Among the care-seeking PIW (n=218), 72.5% turned to private health facilities or qualified private practitioners, while only 6% utilized public health facilities, and 11.5% accessed both public and private facilities. The qualified practitioners include gynecologists, obstetricians, reproductive endocrinologists, and trained general practitioners. The remaining 10% of those seeking care sought help from other health centers or locations (e.g., NGO static clinics, NGO depo holders, non-qualified doctors’ offices, pharmacies, etc.). Nearly all (95%) of individuals who visited a public or private health facility or consulted a qualified provider underwent medical testing, whereas only 35% of those seeking care from other locations /providers (traditional healers) did so. Among those who did not seek care (n=20), more than half (55%) indicated they preferred to wait for spontaneous conception, and 25% mentioned their husband was not in favor of it. (Figure 1).

Findings from the IDIs also support the patterns and locations of care-seeking. All PIWs initially sought care from traditional healers, with the majority (9 out of 10) selecting them as their primary point of contact. Respondents indicated that traditional healers primarily treated women. This preference for traditional healing practices arises from the belief that infertility goes beyond conventional medical intervention, shaped by spiritual and religious views of the condition. Factors such as proximity and lower cost also informed this choice. However, a significant shift toward seeking care from qualified medical providers (9 out of 10) was observed as treatment progressed. Couples (6 out of 10) predominantly relied on recommendations from family and friends when selecting medical providers, often prioritizing those in their neighborhood or nearby homes. Accessibility and cost were also important factors in this decision-making process. Notably, a substantial proportion (4 out of 10 couples) sought care at tertiary healthcare facilities in Dhaka, with one couple pursuing treatment from a neighboring country (India). All couples who opted for qualified providers sought treatment from private healthcare facilities. One of the IDI respondents (husband) shared their challenges and frustrations while undergoing infertility treatment:

“Not just one; we went to several places for KABIRAJI treatment. We even visited top doctors in Dhaka, waiting in long lines for our turn. … It was such a lengthy process. At one point, we asked if we could complete one person’s treatment, either mine or my wife’s, before moving on to the other, but they insisted that it had to be done together. … We spent nearly all our money on it and even had to take out loans. This treatment isn’t for poor folks like us.”

MEDICAL TESTS FOR INFERTILITY DIAGNOSIS

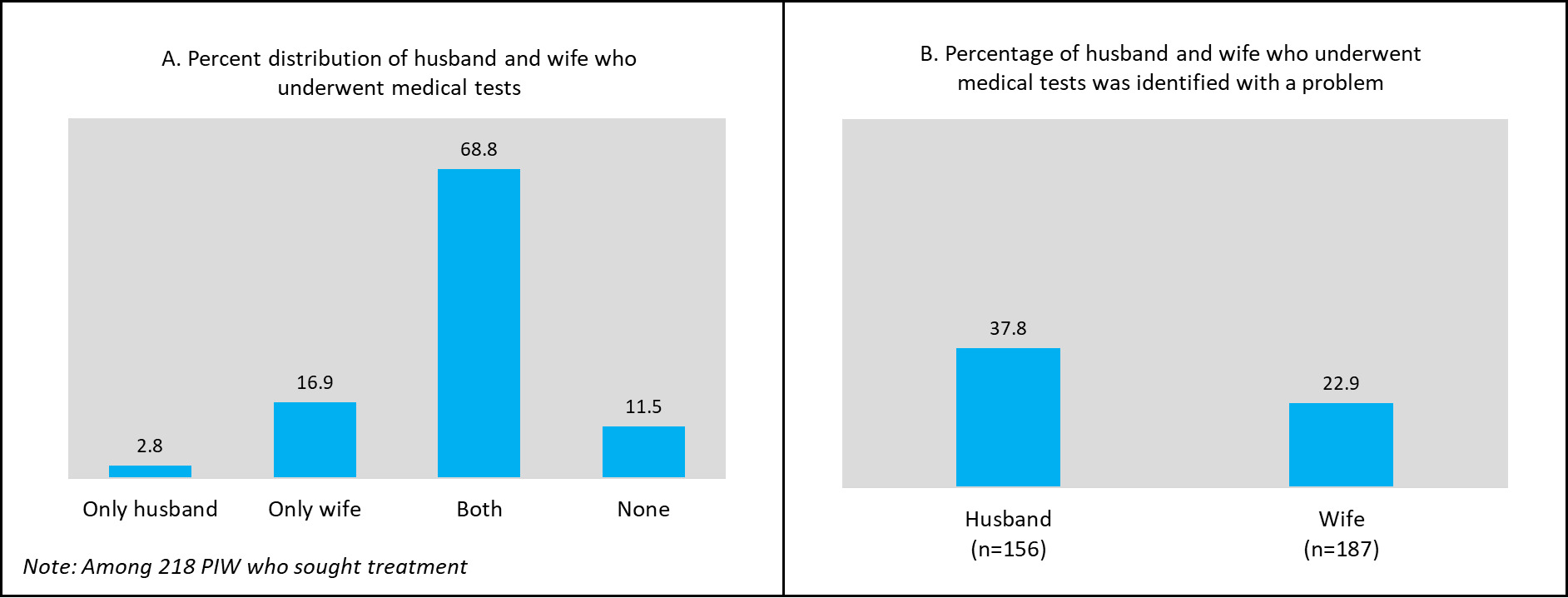

A total of 193 out of 218 care-seeking PIWs reported undergoing medical tests for infertility investigation, which represents 89%. Among them, 69% indicated that both they and their husbands had undergone the medical tests, while 17% of women stated that only they had undergone the tests, and 3% reported that only their husbands had undergone the tests (Figure 2, Panel A). Thirty-eight percent of the men (husbands) who underwent a medical test were diagnosed with a problem, which was 23% among the women (wives). In the survey, we did not find any case where both husband and wife were diagnosed with a problem. However, an IDI respondent reported that both of them were diagnosed with a health problem. The IDIs were conducted after the survey. It might happen that they underwent a medical test after the survey. (Figure 2, Panel B).

The findings were supported by those revealed from the IDIs. Nine out of ten IDI participants underwent medical tests. One of the husbands had health issues among four couples; only the wife had any health issues among four couples, and both the husband and the wife had some kind of health issues in one case. Women primarily reported menstrual issues, while husbands commonly encountered azoospermia or thin semen as the main concern.

INFERTILITY TREATMENT AND TREATMENT DISCONTINUATION

Among the care-seeking PIWs (n = 218), 95% (207) received medication, regardless of whether they underwent any medical tests. Of the 207 PIWs, 90% (186) continued the medication until the survey date. Among the other 21 PIWs who did not continue the medication, 7 cited financial hardship as the reason for discontinuation, 5 mentioned a lack of family support, and 9 expressed losing faith in the treatment.

The IDIs also found that most care-seekers continued treatment for at least six months (8 out of 10). However, nearly all couples eventually discontinued treatment, with two choosing adoption and only one opting for traditional medicine. Financial constraints were reported as the primary reason for discontinuation. The reported treatment costs varied from BDT 70,000 to 700,000, depending on the healthcare provider and the number of visits. One 26-year-old woman who had been trying to get pregnant for the last six years expressed her financial constraints as follows:

“When you visit a new doctor, they request that you repeat all the tests. The doctor suggested medicines that cost 500 BDT per week. My husband purchased the medicines for a few weeks, but then stopped. We have no money left, so how can I continue my treatment?”

Other reasons for discontinuing treatment, as identified in the IDIs, included frustration over not achieving desired results and a loss of confidence in its effectiveness. While a lack of family support wasn’t directly indicated, one woman shared that a significant portion of her treatment expenses, especially those related to diagnostic tests, were paid for by her parents instead of her husband or in-laws.

DECISION-MAKING FOR INFERTILITY CARE-SEEKING

Eighty-eight percent of survey respondents indicated that care-seeking decisions were made jointly by husbands and wives, while 8% noted the involvement of other family members (Figure 3). In a few instances, the decision was made solely by the wife (4%) or the husband (1%). The in-depth interviews also highlighted that joint decision-making is common for infertility care-seeking, with 8 out of 10 participants reporting this approach. This process is often initiated following family discussions regarding perceived delays in conception, as well as facing disrespectful comments from relatives and neighbours, and experiencing societal pressure to conceive. One participant from an in-depth interview (a husband) shared their understanding as a couple, their care-seeking journey, and their decision-making process in care-seeking as follows:

“We began with homeopathy, visiting several homeopathic doctors, and then made the decision together to go to the city (district town) for medical tests to determine why we were unable to get pregnant.”

OBJECTIVE 2. AVAILABILITY OF ESSENTIAL INFERTILITY CARE

COMPONENTS OF INFERTILITY CARE

The key informants identified three important components of infertility care: diagnostic tests, first-line treatment, and advanced treatment. Common diagnostic tests include semen analysis, hormone levels: FSH and LH, and Transvaginal Sonography (TVS). The first-line treatment includes Tablet Clomiphene Citrate + Letrozole, Injection Recombinant FSH/LH, and Intrauterine Insemination (IUI). The advanced treatment includes in vitro fertilization (IVF) and ovarian rejuvenation/platelet-rich plasma (PRP)/stem cell therapy. (Table 2)

AVAILABILITY OF INFERTILITY CARE COMPONENTS IN DIFFERENT TIERS OF HEALTH FACILITIES

Among the diagnostic tests, only semen analysis is available in some primary and higher-level public health facilities; however, it is not universally available across all facilities at these levels. The other three tests are only offered in selected tertiary or specialized public health facilities. None of the first-line or advanced treatments are provided in public primary-level health facilities. Tablet Clomiphene Citrate combined with Letrozole is available in secondary health facilities, and no other first-line or advanced treatments are available there. All first-line treatments are available in selected tertiary and specialized health facilities. BSMM University (BSMMU) is the only institution in the country that offers advanced infertility treatment. Key informants were aware of the availability of private facilities providing infertility care; however, they were not well-informed about which facilities offer specific services. The key informants also emphasized the importance of documenting private facilities that provide infertility care, along with the types of services they offer. (Table 2).

OBJECTIVE 3. CHALLENGES, OPPORTUNITIES, AND ESSENTIAL POLICY ACTIONS FOR INFERTILITY CARE

CHALLENGES IN INFERTILITY CARE

We summarized a comprehensive set of challenges in infertility care in Bangladesh based on the key informant interviews. These challenges can be categorized into three broad areas: supply-side, demand-side, and other challenges. Numerous supply-side issues have been identified, including a shortage of infertility specialists, trained providers, and technicians, inadequate availability of essential equipment, logistics, and technologies, limited access to infertility care facilities outside the capital city, and the lack of a national infertility action plan and guidelines. Demand-side challenges comprise a lack of awareness about infertility care, care-seeking after passing the appropriate age for the treatment(e.g., after age 35), high rates of treatment dropout, and reliance on traditional healers as the initial point of contact. Furthermore, the high cost and lengthy nature of advanced infertility treatments represent an additional challenge that is worsened by both supply-side and demand-side issues. (Table 3)

OPPORTUNITIES IN INFERTILITY CARE

Infertility care opportunities are quite limited in the country, with Dhaka Medical College Hospital (DMCH) and BSMMU being the two facilities that show promise in advanced treatment options. Additionally, infertility-focused specialized courses and training offered by the Bangladesh College of Physicians and Surgeons (BCPS) and BSMMU are expected to enhance professional capacities in the field. The Fertility and Sterility Society of Bangladesh also offers hope in infertility care by generating evidence and facilitating discussions for the infertility care movement. Despite the limited supply-side opportunities, seeking care at an early age (e.g., before 30) and increasing men’s engagement in seeking care are significant demand-side opportunities. It is encouraging that most patients undergoing initial treatment achieve pregnancy within 6-8 months [within 6-8 menstrual cycles of a woman]. (Table 3)

POLICY ACTIONS NEEDED FOR INFERTILITY CARE

The key informants identified several immediate policy actions to enhance infertility care and improve access and affordability. They recommended short-term training on infertility for grassroots healthcare providers at primary care facilities. Additionally, they advised increasing diagnostic capabilities in primary and secondary health facilities, decentralizing first-line infertility treatments to secondary-level health facilities, decentralizing advanced treatments at all tertiary or specialized facilities, establishing specialized infertility care centers outside of Dhaka, and providing subsidies for ART care. They highlighted the need for a national infertility action plan and standardized guidelines for public and private care centers/providers regarding treatment and appropriate referrals. (Table 3)

DISCUSSION AND RECOMMENDATION

This study examined care-seeking for infertility in two rural areas of Bangladesh, as well as the availability, challenges, and opportunities of infertility care in the country. It revealed a high level of care-seeking (which often indicates demand) among potentially infertile couples, reliance on traditional healers, the involvement of both husband and wife in the care-seeking decision-making process, and the unacceptably low availability of infertility services nationwide.

The study reveals an encouragingly high rate of infertility care-seeking (92%), as indicated in earlier qualitative studies conducted decades ago.23,24 It reflects a long-standing belief in the community that infertility or delays in conception are treatable health conditions. The involvement of both the husband and wife in the decision-making process regarding care-seeking is also beneficial in reducing misunderstandings and fostering mutual respect. However, the initial choice to consult traditional healers indicates a lack of awareness about appropriate medical care sources for these conditions. Traditional healers often serve as the primary point of contact in rural areas due to their accessibility, affordability, and cultural familiarity; their involvement presents both opportunities and challenges. They play a significant role in local health-seeking traditions and may offer psychological comfort. On the other hand, delays in seeking biomedical care due to overreliance on traditional remedies can hinder timely diagnosis and effective treatment.32,33 Integrating awareness programs that engage community leaders and healers may help shift harmful norms while respecting cultural sensitivities. Outreach programs focused on infertility and its care are likely to enhance awareness and knowledge.

Training and utilizing the family welfare assistant, a community-level government family planning (FP) worker who is expected to visit all households in her service area to provide FP information and products, should be one of the easiest interventions to enhance community awareness.24,34,35 It aligns with her primary job responsibilities. Such intervention will help the potentially infertile couples, who never sought care, overcome barriers to care-seeking and ensure early diagnosis and treatment. Community-based initiatives are also likely to improve social norms and reduce disrespectful attitudes toward infertile couples, particularly women.29,36,37 The interventions may include awareness programs that spread the understanding that infertility is a treatable health issue and is not only a woman’s problem. Additionally, it is important to communicate where these services are available.

Another promising fact is that a high proportion of infertility care-seekers underwent medical tests (89%) for diagnosis, and 8 out of 10 IDI couples continued treatment for at least six months. The primary reasons for treatment discontinuation are financial constraints, inadequate family support, the lengthy treatment process, and a lack of trust in the treatment received. This highlights the demand-side challenges, which are compounded by supply-side inadequacies. Since menstrual problems are common among many care-seeking women, first-line treatment in primary health facilities should address these issues.38,39 However, basic infertility diagnostic tests (such as hormone level and semen analysis) and medications for first-line treatment are unavailable in primary health facilities.20,40 Care-seekers must travel long distances to major cities/district headquarters for basic diagnostic tests and initial treatment.27,28 Our key informant interviews revealed that 80% of infertility cases can potentially be managed with first-line treatment, which gynecologists can administer without specialized training. This finding highlights the opportunity to decentralize infertility care and enhance capacity at lower levels of the health system, thereby reducing burden on tertiary/specialized care centres. It requires policy attention to ensure that basic infertility tests and first-line treatment are available in primary health facilities.20,26,27 Advanced treatment, available only at BSMMU, should be provided at all secondary health facilities.

Private sector initiatives must not be neglected in infertility care provisions. Bangladesh has witnessed the significant contributions of private sector efforts to healthcare improvements over the past three decades. A similar situation is likely to occur in infertility care.27 However, that must be monitored by the appropriate authorities. Even renowned infertility specialists are unaware of the quality of services offered in the private sector. The national health facility survey, conducted periodically in recent years, may begin collecting data on the availability and quality of infertility services from both public and private facilities to bridge the information gap and support evidence-based inputs into national action plans.

The above discussion illustrates how Bangladesh is grappling with significant limitations in infertility care, both on the demand and supply sides. Highlighting these limitations and reflecting on past and present challenges is crucial to understanding our current situation. Exploring opportunities is even more vital to overcoming today’s obstacles. We have already learned that couples tend to support each other during conception delays and make joint decisions about care-seeking. Now, the supply side must ensure that couples seeking care receive appropriate primary services from health facilities and that proper referrals for advanced care are made.

As suggested by key informants, supply-side initiatives should begin with the development of a national action plan for infertility care and the organization of short-term training for providers at primary and secondary health facilities. Short-term training for community-level staff, such as family welfare assistants, health assistants, and community health care providers, will foster awareness at the community level. Such capacity-building programs may receive support from institutions such as BSMMU, DMCH, and FSSB, among others. Infertility specialists in these institutions possess extensive experience in tackling infertility. These specialists will also play a key role in guiding the development of the national infertility action plan, which must include comprehensive guidelines on the availability and quality of services for providing these services.

Additionally, key informants emphasized the need to address workforce shortages in infertility care. The true magnitude of the shortage is unknown. Expanding academic courses on infertility at BSMMU and the Bangladesh College for Physicians and Surgeons will help increase the number of trained professionals in the country. Sanctioning posts for trained infertility care providers across the country and ensuring their presence will also be crucial. Provider vacancy or absence in the workplace has been a chronic issue in the country’s health service systems. For example, 25% of general physicians and 58% of specialist posts remain vacant in the country.41

Advanced infertility treatment is often costly, leading to treatment discontinuation. However, the percentage of couples requiring advanced treatment is relatively small. Government subsidies for infertility care at public health facilities, along with financial support from development partners or philanthropists, may assist low-income infertile couples in need of advanced treatment. For instance, governments in Turkey, Pakistan, and China provide subsidies for advanced infertility treatments, while many European countries, including Belgium, the UK, and Estonia, offer similar subsidies.11,42 In the United States, private foundations such as the Baby Quest Foundation and the Wyatt Foundation provide couples with financial assistance for IVF treatment.43 Additionally, global charitable organizations, such as the Merck Foundation, collaborate with governments (e.g., Malawi) to train local doctors in advanced infertility treatments, enabling the provision of this care at the community level.44 Evidence-based action plans are crucial for the success of such initiatives.

Future research would explore infertility care-seeking behaviors in urban areas, where infertility prevalence may be higher due to lifestyle and environmental factors. Further investigation is also needed to understand the experiences of couples who remain childless following lengthy treatment or ART. Facility-based assessments and longitudinal studies could offer more precise estimates of service gaps, treatment outcomes, and the economic burden of infertility on households.

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

The study provides population-based evidence on different perspectives of infertility care in two rural areas of Bangladesh. It does not encompass the urban population, where infertility is more common or anticipated to be more prevalent due to factors linked to infertility that are more frequently found in urban settings.45 However, the overall findings and study recommendations are likely to benefit everyone. Another limitation is that the study examined infertility care-seeking but did not investigate the types of medical tests and medications the participants received.

One criticism of the study is that it was conducted at two HDSS sites, which often receive different types of health interventions. However, since neither of the two HDSS sites was exposed to infertility interventions, the study findings are unlikely to be influenced by other characteristics of the HDSS.

The sampling frame included currently married women, thus excluding those who experienced marital dissolution due to infertility, meaning the findings do not reflect their experiences. Nevertheless, the third objective of the study is independent of the context involving infertile couples, and the results from the first and second objectives are expected not to be significantly impacted by the exclusion of women who underwent marital dissolution due to infertility, as this group constitutes a relatively small portion.

The study also overlooked cases of infertility where individuals succeeded in conception after treatment, as it only included couples who were still facing delays in conception. Consequently, the care-seeking and treatment pathways, as well as the challenges and supports experienced by those couples who faced delays in conception but ultimately conceived after treatment, were not reflected in this study. However, key informants, drawing on their experiences, provided additional information that somewhat mitigated this limitation.

While a health facility survey would be ideal for evaluating the availability of infertility services, we relied on insights from key informants (infertility specialists and care providers) due to resource constraints. Nonetheless, 6 of the 8 key informants were among the country’s most knowledgeable infertility service providers. They are familiar with the overall availability of infertility services nationwide, and the detailed information we received from them is likely to reflect the current state of infertility care in the country.

Lastly, the sensitive nature of infertility might lead some participants to misreport their experiences or care-seeking behaviors, and the exclusion of women whose marriages dissolved due to infertility might have limited the diversity of perspectives captured. Moreover, qualitative findings may not be generalizable beyond the rural settings studied, although they should offer valuable information for similar socio-cultural contexts.

CONCLUSION

Infertility care-seeking is prevalent but often starts with traditional healers due to a lack of awareness. Community-level awareness programs may help encourage seeking care from trained providers. To achieve this, it is crucial to ensure the availability of primary infertility diagnosis and treatment in both primary and secondary public health facilities. A national infertility action plan, the immediate enhancement of capacity through short-term training, and advocacy for integrating infertility issues into health sector programs are vital for improving infertility services in the country. These efforts will go beyond strengthening service delivery by contributing significantly to women’s mental health, enhancing social well-being, and promoting family stability.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

MMH, QN, and FNR conceptualized the research problem. SSS, FNR, and MTA compiled the data and analyzed it under the guidance of KJ, QN, and MMH. MMH, FNR, and MTA prepared the draft. FNR, MTA, and N performed the literature review. QN reviewed the manuscript and provided feedback. MMH, MTA, and MMA revised the paper to address the comments. All authors reviewed and approved the final version.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank the study respondents and key informants who voluntarily participated in the study, the field workers for their dedication and hard work, and the administrative staff for supporting the activities throughout the project period. icddr,b is grateful to the governments of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh and Canada for providing core/unrestricted support.

FUNDING

This research protocol/ activity/study was funded by the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development (DFATD), through Advancing Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (AdSEARCH), Grant number: SGDE-EDRMS-#9926532, Purchase Order 7428855, Project P007358. icddr,b is also grateful to the Government of Bangladesh and Canada for providing core/unrestricted support.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data will be available upon request, and under the condition of using it only for this study.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of icddr,b before conducting the study (Protocol number: PR-22062). Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants. Anonymity, confidentiality, and respect for participants’ dignity were upheld throughout data collection, analysis, and reporting.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

All author gave their consent.

COMPETING INTERESTS

None.