Antiretroviral therapy (ART) has profoundly impacted the global HIV epidemic, markedly reducing both morbidity and mortality among people living with HIV (PLHIV) .1 Between 2010 and 2023, new HIV infections declined by 39%, and HIV-related deaths fell by 48%, saving an estimated 13.6 million lives. Despite this progress, significant gaps in ART coverage persist. In 2023, of the 39.9 million PLHIV globally, only 30.7 million (77%) were accessing ART, leaving approximately 9.3 million without life-saving treatment.1 While ART access improved from 47% in 2010 to 77% in 2023, disparities remain across populations and regions.1 Women had higher ART access (83%) than men (72%), and only 57% of children aged 0–14 were receiving ART. Geographically, ART coverage ranged from 93% in Eswatini to 47% in South Sudan .2 Loss to follow-up (LTFU) remains a major barrier to achieving the UNAIDS 95-95-95 targets by 2030. LTFU is generally defined as the failure to refill ART medication or attend clinical contact within a specified period, often without successful tracing.3,4 This leads to interruption in treatment (IIT), which PEPFAR defines as missing clinical contact for 28 days or more same as WHO definition of LTFU. In sub-Saharan Africa, LTFU rates are high, ranging from 20% to 40%.5,6 A Ugandan study found that only 39% of traced clients and 61% of self-returning clients were retained after 18 months. In Kenya, around 1.38 million people are living with HIV, with ART coverage exceeding 98% among those with a known status. However, LTFU remains a challenge.7. A 2023 study across 87 Kenyan HIV clinics found high rates of LTFU and mortality among adolescents and young adults (10–24 years), even after re-engagement in care.8 Risk factors for LTFU vary. In central Kenya, men, unmarried individuals, those aged 20–35 years, and patients with advanced HIV (WHO stage III/IV) or presumptive/unknown TB status had higher LTFU risk.9 In southern Ethiopia, LTFU was more likely among patients under 35 years and rural residents. Surprisingly, patients with baseline weight over 60 kg had increased LTFU risk, possibly due to unmeasured factors.10 Kenya’s 2022 National ART Guidelines recommend tracing strategies including phone calls within 24 hours of missed appointments and home visits.11 To address this gap, a Return to Care (RTC) package was introduced in select PACT Timiza-supported facilities. This package provides structured counseling, identifies barriers to retention, and delivers client-centered interventions. Integrated services such as nutrition counseling and linkage to non-communicable disease (NCD) management are also included, especially for high-risk clients. Despite the rollout of the RTC package, evidence on its effectiveness is limited. This study aimed to evaluate the incidence of subsequent LTFU among clients who received the RTC package compared to those who received standard care. Additionally, we explored factors associated with LTFU following re-engagement in care to inform future strategies for sustained ART retention.

METHODS

Study design and population

University of Maryland, Baltimore (UMB) Partnership for Advanced Care and Treatment (PACT) Timiza program in Kisii and Migori Counties, Kenya as of September 2018 supported 65,512 clients on care and ART in 182 sites. Of the total 182 supported sites, 65 facilities that contributed to highest interruptions in treatment implemented the RTC package as a Quality improvement (QI) intervention aimed at reducing the losses and retaining those who return to care after reengagement. We used a retrospective cohort study design to evaluate impact of RTC package among HIV care clients who were LTFU in 65 supported health facilities (sites) as of September 2018. The study population consisted of PLHIV (children and adults) on care who were once LTFU at any given time then came back to HIV care between October 2018 and September 2019. UMB PACT-Timiza program was a 5-year cooperative agreement funded by the PEPFAR through the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Kenya.

Structured RTC package

The structured RTC package (Table 1) builds upon the standard care outlined in the 2022 Kenya National ART guidelines. It features a defined client flow and adherence barrier analysis at re-engagement, conducted by trained psychosocial counselors who categorized barriers as social, mental, or psychological and developed client-specific action plans. Counseling focused on lifelong ART, appointment adherence, and follow-up actions, with tailored schedules based on identified barriers. Each client was assigned a case manager and peer supporter to provide ongoing support, including home visits and weekly check-ins. Clients were referred to relevant support groups based on their profiles. Locator forms were updated with alternative contacts to improve tracing, and case managers presented weekly progress updates in QI meetings. All follow-up was documented in the case management register to ensure continuity of care. Table 1 highlights the additional components of the RTC package compared to standard care for clients returning after missed appointments.

Data collection

Data collection occurred from September 2019 to June 2020. Patient demographic data, ART regimen, and treatment outcomes such as Viral Load were recorded in paper charts, registers, and EMRs. A standardized tool was used to abstract data from non-EMR sites and entered in an excel database with validation checks. EMR data were extracted electronically. Non-EMR data were more prone to incompleteness and field validation minimized discrepancies. Health Records Officers reviewed data for consistency before site exit. All client-level data were anonymized using unique IDs and stripped of identifiers, then merged for analysis.

Definition of variables

The primary outcome variable was subsequent LTFU after offering RTC package, defined as clients who had not had a clinical encounter within the 28 days after their last scheduled clinic visit, according to PEPFAR1.The main exposure of interest is the RTC package. Sites that adopted RTC packages were assigned a “1” and those that did not adopt RTC packages were assigned a “0”. The mode of re-engagement in care was categorized as “self,” for those who returned in care of their own volition, or “traced,” for those who returned in care after being traced. ART dispensing was categorized as “standard,” for those who received a monthly supply, or “multi-month scripting,” for those who received multi-month prescriptions.

Statistical analyses

Frequencies and proportions were reported for categorical variables, and medians with interquartile ranges for continuous variables. Chi-square tests assessed differences in categorical variables. Clients accrued person-time from re-engagement in care until LTFU, death, transfer, or study end, with non-LTFU events censored. LTFU incidence and 95% CIs were calculated per person-months. Initial models without covariates estimated overall and group-specific LTFU incidence. Overdispersion was assessed using a score test.12 Log-rank tests compared LTFU probabilities at 3, 6, and 9 months by RTC package status. Adjusted Cox models evaluated the association between RTC and LTFU, informed by bivariable analysis and directed acyclic graphs. Covariates with p<0.25 or plausible links to LTFU were included; regimen type and ART dispensing method were excluded. Site clustering was accounted for using frailty models. Missing covariate data (e.g., BMI, marital status) were handled via five multiple imputations under a missing-at-random assumption, with final estimates pooled using Rubin’s Rules.13 Results from imputed and complete case analyses were compared. Adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) with 95% CIs were reported. Sensitivity analysis by age and gender assessed robustness. Analyses were conducted at 5% significance using SAS v9.4. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the University of Maryland Institutional Review Board and the Kenya Medical Research Institute Scientific and Ethics Review Unit (KEMRI SERU). This project was reviewed in accordance with CDC human research protection procedures and was determined to be research, but CDC investigators did not interact with human subjects or have access to identifiable data or specimens for research purposes.

RESULTS

As of September 2018, the PACT Timiza program supported 65,512 clients on care and treatment from 182 supported sites, of whom 52,849 (81%) were from 65 selected supported sites for QI projects. The minimum number of PLHIV in one of the 182 sites was 6 while the maximum number was 5,022 PLHIV. The program reported a total attrition of 5,497 clients from 182 supported sites of whom 3,827 (70%) were from 65 supported sites. Of the total attrition, 2,305 were LTFU, of whom 1,580 (69%) were LTFU from the 65 selected sites. Of these 1,004 LTFU were audited and hence selected and included in the analysis, 857(85%) returned to care while 147 (15%) never returned, (Figure 1). Of the 857, 584 (68.14%) were offered RTC package, 548 (63.94%) were females and 689 (80.40%) were ≥ 25 years). The majority, 783 (91. 36%), were on first-line ART, 567 (66.16%) re-engaged in care after being traced, and 192 (22.40%) were receiving multi-month ART prescriptions (Table 2).

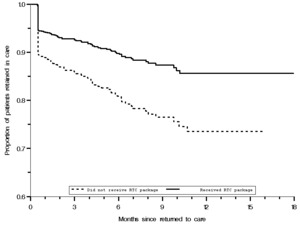

Retention probability distributions among those who received RTC package and those who did not receive RTC package

The final Poisson regression model (Table 3) included 796 (92.88%) participants with a documented last visit date, of whom 102 (12.81%) individuals were lost after 4,658.1 person-months (PM) (incidence rate (IR) 2.21 per 100 PM; 95% CI: 1.82–2.68). Overall, the median follow-up period was 5.1 (IQR, 1.7– 8.7) months. Those who received RTC package had a median follow-up period of 5.9 (IQR, 2.0 –10.4) months. The corresponding median follow-up period among those who did not receive RTC package was 3.9 (IQR, 1.2– 6.5) months. Among those who received the RTC package, 56 were lost to follow-up (LTFU) with an incident rate (IR) of 1.58/100 PY (95% CI 1.21-2.05), compared to 47 among those who did not receive RTC package (IR = 4.25/100 PY; 95% CI 3.19-5.66). The difference in LTFU probabilities was evident from the start of follow-up. Kaplan–Meier curves indicated a sharp decline in clients retained in care for those without the RTC package (Figure 2). The probability of patients being LTFU at 3, 6, and 9 months was 24%, 20%, and 24%, respectively, among those who did not receive RTC package compared to 7%, 10%, and 13%, respectively, among those who received the RTC package (p<0.001, log-rank test).

Results on Factors associated with LTFU: Complete Case Analysis (CCA) (n = 467, (58.7%) and after Multiple Imputation (n = 796)

Table 4 displays Hazard Ratios (HR) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) estimated from complete case analysis and multiple imputation of missing covariates. The estimates were similar in effect magnitude and direction, though complete case analysis showed wider 95% CIs due to a 41.3% loss of information. Bivariate analysis from complete case analysis indicated that participants receiving RTC packages had a significantly lower risk of loss to follow-up (LTFU) compared to those who did not (unadjusted HR 0.50; 95% CI [0.34–0.74]). Clients aged ≥ 25 years were also less likely to be lost to follow up (uHR 0.67; 95% CI [0.43–1.04]). The final multivariable model included age, sex, education, BMI, and RTC package indicator. In this analysis, age (≥ 25 vs. < 25 years; adjusted HR [aHR] 0.42; 95% CI [0.23–0.75]) and BMI (normal weight vs. underweight; aHR 1.88; 95% CI [1.02–3.47], overweight vs. underweight; aHR 2.30; 95% CI [1.13–4.67]) were associated with LTFU.

Analysis after multiple imputation found comparable results, with RTC package recipients having a lower risk of LTFU (uHR 0.50; 95% CI [0.34–0.74]). In this analysis, females were more likely to be LTFU (aHR 1.80; 95% CI [1.10–2.95]), and multivariable analysis confirmed that both RTC packages and sex were significantly associated with LTFU: those receiving RTC packages were 43% less likely to be LTFU (aHR 0.57; 95% CI [0.38–0.78]), while females were more likely to be LTFU compared to males (aHR 1.84; 95% CI [1.15–2.93]).

Sensitivity analysis

In a subgroup analysis, recipients of the RTC package were less likely to get lost compared to non-recipients across all age groups. For those aged 25 and older, receiving the RTC package was linked to a 43% reduction in the risk of LTFU (HR 0.57; 95% CI (0.36–0.89)). However, no significant difference was observed for those younger than 25 (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

We observed significantly fewer cases of loss to follow-up (LTFU) after treatment interruption at sites implementing a return-to-care (RTC) package in Kisii and Migori Counties, Western Kenya. Clients receiving the RTC package had a 43% reduced risk of LTFU, underscoring its value for PLHIV at risk of disengagement. Similarly, a study in Malawi reported improved retention after re-engagement, with attrition rates of 12%, 16%, and 18% at 6, 12, and 24 months, respectively, attributed to a shift in client mindset fostered by compassionate care from providers.14 HIV treatment is lifelong, and interruptions can result in poor health outcomes, increased transmission risk, and drug resistance. Therefore, it is crucial to implement interventions that help clients stay in continuous care.15,16 A review of the literature indicates that clients who discontinue and then reinitiate care are at higher risk of death or stopping ART due to advanced HIV disease.17 It is essential to evaluate the barriers to retention in care for these clients, as it affects ART adherence. A study in Uganda found that 52% of clients re-engaged in care after interruption remained active on follow-up at 18 months, while 39% were successfully traced, and 61% returned before tracking.18 In this retrospective cohort study, we showed that a higher proportion of clients who initially disengaged from care were retained, even after 9 months of follow-up, after receiving structured RTC package including psychosocial counselling that addressed social, mental, or psychological factors associated with LTFU. A qualitative study in SSA showed that caring for a sick family member, traveling for work, and attending a relative’s funeral in a different location were prioritized by the client over a clinic appointment.19 Long travelling distances to clinic and opting for nearby, decentralized services were some of the reasons cited by clients.19 In addition, harsh and disrespectful treatment from health care providers following disengagement in care is one of the reasons for LTFU .20 Strategies to minimize disengagement and facilitate retention for those returned to care are important. Prior data shows that clients out of care account for 60% of new HIV infections .21 This data underscores the need to re-engage and retain PLHIV in care to control the HIV epidemic. In this study, clients who received RTC package also received a structured barrier analysis as one of the strategies and client-centered solutions were utilized. For example, flexible appointments were given to accommodate those travelling for funerals and work. This could explain differential retention between participants who received RTC package compared to those who did not.

HIV-related stigma and lower literacy levels among females may hinder adherence support and limit the benefits of the return-to-care package. In contrast to our findings, a study in Ethiopia found men more likely to have poor outcomes after returning to care. Further qualitative research is needed to explore unaddressed barriers among female clients.15,22 Qualitative studies need to be done to understand the barriers that may not be addressed by the package of care among the female clients. We also found that age was associated with LTFU in complete case analysis—clients aged 25 or older had a 58% lower likelihood of becoming LTFU. However, this association was not significant after multiple imputation. Adolescents and young adults face unique challenges such as disclosure, transition to adult care, and social pressures, which may contribute to poorer ART outcomes, including LTFU.23,24 Similarly, BMI was associated with LTFU in complete case analysis but lost significance after multiple imputation. Obesity appeared protective against treatment interruption, possibly due to the need for regular hospital visits related to obesity itself, integrated nutrition counselling within HIV care, and co-existing NCDs like hypertension and diabetes requiring follow-up. A study by Teshome in Ethiopia also found that higher BMI was linked to a nearly 40% reduced risk of LTFU .25 Enhancing nutritional support and integrating NCD management into HIV care may improve continuity of treatment among clients with obesity, though this contrasts with a Malawi study that found no association between BMI and retention post re-engagement.14 The main limitation of this study was the use of routine data, resulting in missing information. We addressed this through multiple imputation, assuming data were missing at random, though sensitivity analyses are recommended to test this assumption. Facilities offering the RTC package were not matched with non-RTC sites by characteristics such as care level or location, as selection was based on ART client volume and LTFU rates. Cost-effectiveness was not assessed due to the intervention being limited to facilities with CQI projects. However, the findings strongly suggest that the RTC package supports improved ART retention.

CONCLUSION

Implementation of the RTC package effectively reduced long-term follow-up (LTFU) issues among PLHIV in 65 healthcare facilities in Western Kenya. This approach enhances retention and supports HIV epidemic control. Policymakers should consider expanding RTC strategies in national HIV retention programs to improve continuity in care. This study’s retrospective design and potential selection bias highlight the need for further prospective research to confirm these findings and refine RTC strategies for broader use. Further studies on cost-effectiveness are essential to understanding the economic viability of scaling the RTC package.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the funding agencies.

Funding

This activity has been supported by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) under the terms of NU2GGH001949.

Authorship Contributions

Violet Makokha led the conceptualization and design of the study, developed the original draft, and led the writing process. Habib Omari Ramadhani contributed to methodological reviews, data analysis, and interpretation of results. Samuel Wafula and Caroline Ngeno provided critical review and contributed to editing and refinement of the manuscript. Emmanuel Amadi, Richard Onkware, Eliza Owino, Elizabeth Katiku, and Paul Musingila supported the review process and provided technical and contextual input throughout manuscript development. Emily Koech provided overall oversight.

Correspondence to

Violet Makokha, Center for International Health, Education, and Biosecurity (CIHEB)-Kenya

KREP Centre, 6th Floor, Wood Avenue, Kilimani, Nairobi

P.O. Box 76604 – 00508, Nairobi, Kenya

Mobile: +254 723097703 Office: +254 20 3908219