INTRODUCTION

Women’s health concerns, and most importantly menstrual health, are underrepresented in basic and transitional research.1 Menstruation, or period, is the part of the menstrual cycle where a woman bleeds from the endometrium (the inner lining of the uterus) throughout her reproductive lifecycle.2 The menstrual cycle lasts an average of 28 days and involves natural changes in a woman’s body that happen when an egg develops and the body prepares for a possible pregnancy. When a woman’s menstrual health is good, women, girls and other menstruators function to their full potential. Good menstrual health is facilitated by both access to menstrual products and the necessary resources needed by menstruators to participate fully in all domains of life during their menstrual cycle,3 but period poverty acts as a limitation for this to be achieved. Half of the world’s women population estimated to be 1.9 billion experience menstruation every month.4,5 Globally, period poverty affects 500 million women of menstruating age.6,7 There exist economic, social, political and cultural barriers that negatively affect access to menstrual products,8 menstrual education material, and sanitation facilities for many women.4,9,10 Period poverty remains a significant global health policy issue that requires considerable policy attention. International scholars have been making great efforts to address the devastating impact of period poverty for over a decade,11–14 but scholars and policymakers in the U.S. are yet to adequately engage in this campaign accordingly.1

Period poverty refers to the social, economic, political, and cultural barriers to menstrual products, education, and sanitation.6 It can also be seen as the lack of access to menstrual products, education, hygiene facilities, toilets, menstrual hygiene education, hand-washing facilities, waste management, sanitary products, or a combination of these barriers due to financial constrainsts.5,6 Period poverty is considered to be a neglected global public health issue due to the limited attention devoted to it by policymakers’ and their stakeholders.15,16 It is a global issue that needs to be addressed by policy stakeholders as a public health crisis.17 Period poverty not only affects menstruating people in poor/low-income countries; it also affects those in rich/high income countries.4,18 Menstruating women in the U.S. are also affected by period poverty, and this poses a lot of threats to these women’s health.4 Women suffering from period poverty also experience socio-economic challenges. Access to menstrual products is a problem in the U.S. for low-income women.19 The negative impact of period poverty became more glaring during the COVID-19 pandemic.19,20

Millions of women of menstruating age are deprived of menstrual hygienic pads.20 According to the Alvarez,5 25 million women in the U.S. live below the poverty line, and this implies that this group of women are more prone to be affected by period poverty. Female students in the U.S. are the most affected due to their vulnerable financial condition. The Alliance for Period Supplies,21,22 an advocacy group for period poverty, states that one in four women in the U.S. struggles to purchase period products due to a lack of income. Two in five women of menstruating age struggle to afford period supplies because they have numerous financial constraints17,21; one in four teens in the U.S. miss class because they lack access to period supplies21,23; while in New York State, 65% of female students attending public schools in Grades 7-12 go to Title 1 eligible schools.23 This reveals their financial status as Title 1 refers to a federal program that provides support to low-income students. The work of Kelley and Jamieson24 asserts that 20% of teenagers who menstruates in the U.S. had difficulty affording menstrual products. It must be noted that between 2018 and 2021, period poverty in the U.S. increased by 35%, with low- and middle-income women highly affected.17

The inability to afford period supplies has led so many women to use unhygienic menstrual products, resulting in unhealthy conditions.25,26 According to Alvarez,5 only four states in the U.S. require that schools provide free menstrual products for students from Grades 6 -12; federal prisons provide free menstrual products to prisoners.

OBJECTIVE OF THE STUDY

This study aims to address the socioeconomic policy impact of period poverty in the U.S. by investigating the economic, social, political, and cultural challenges to accessing menstrual products and menstrual education.

METHODS

The methodology used in this study is content analysis and ethnographic research design.

This study explores secondary sources of data by making use of journal articles, textbooks, official government documents, and other related sources. The researcher used his keen observation of period poverty’s impact on the society to complement the facts obtained from secondary sources.

Theoretical framework

This study uses the social construction of target population theory to assess why policy stakeholders devote little or no interest in making sustainable policies that will effectively address period poverty.

This theory serves as an approach to understanding the public policy process and policy design by demonstrating how policy designs shape the social construction of policy’s targeted population, the role of power in this relationship, and how policy design shapes politics and democracy.27,28 In this theory, Schneider and Ingram29 assert that policymakers are highly influenced by powerful, and positively constructed target population where they provide them with enormous benefits. Tenets of this theory shape the policy agenda and the actual design of policy. This theory contributes to agenda setting, legislative behavior, policy formulation and design, participation style, and citizens’ conception and orientation.29,30

The theory further asserts that some groups are advantaged more than others, independent of traditional notions of political power and how policy designs reinforce or alter such advantages.29 It posits that society is most likely to see systematic biased policy patterns because policymakers are incentivized to reward positively constructed groups, that is, politically powerful groups.28–30 This depicts why some groups are more likely to be given more policy attention than others or be allocated more government resources/benefits than others.

This theory fits well within the dynamic of the U.S.'s policy-making process where policies in the area of menstrual health (period poverty) are the focal point. Globally, policy stakeholders do not view period poverty as a significant health dilemma that deserves to be at the helm of the policy agenda15; in the U.S., period poverty receives extremely limited policy focus from the federal to local governments compared to other policy spheres. When individuals faced with period poverty are considered a target population in the U.S.'s policy making process, the problems that these individuals face is of limited importance to policy makers because period poverty has received very minimal policy attention from policy stakeholders.

The contemporary state of period poverty in the United States

According to a 2023 survey by Statista,31 23% of teenagers in the U.S. struggle to afford period products, 40% have worn period products longer than recommended, while 62% rarely or never find free period products in public bathrooms. Sacca et al.4 states that 16.9 million women in the U.S. suffer of period poverty as of 2023, and the Alliance for Period Supplies21 posits that 1 in 4 students in the U.S. struggle to afford period products.

As of January 8, 2024, 21 states in the U.S. have sales tax on period products which ranges, for example, from 4% to 7% in Indiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee.21,32 Only five U.S. states do not have a sales tax on period products, these states are Alaska, Delaware, Montana, New Hampshire, and Oregon.21,32 It should be noted that 33 U.S. states plus Washington D.C. do not have a general sales tax on food, while five states tax food at lower rates compared to other products due to the basic necessity of food.21,22 Period supplies fall under a similar basic necessity class but it has not received such support from many state governments.7

DISCUSSION

Economic challenges of period poverty in the United States

Period poverty negatively affects the economic live wire of the state considering that low-income and middle-income women are greatly affected by it, and they play a significant role regarding the wealth of the state.15,17 Period poverty is an economic issue that emanates because some women/girls lack the economic means to afford menstrual hygienic products. The economic impact of period poverty is reflected in several ways, both at the individual level to the community (local) and national level. Regarding school-aged girls who do not have access to period products, Figure 125 shows the vicious cycle that period poverty reproduces women with low status or low economic status in society.

Figure 1 indicates that a lack of access to period products causes school absenteeism for school-aged girls of menstruating age,7 thereby respectively leading to poor grades, school dropout or a lack of interest in school, a low-level job, and low status of women in the society.25 From an economic perspective, the lack of access to period products can lead to the inability to have a good job because, during their education, women who are affected by period poverty regularly stay out of school to avoid embarrassment, thereby causing them to have poor academic performance which also affects their ability to acquire good jobs upon graduation.

Period poverty also causes women to be absent from work due to the shame and stigma that surround their cycles, as well as an anxiety surrounding bleeding.7 This consequence makes women of this category to have low status in society because they are economically fragile.

Cost of period products

The tampon tax levied on menstrual products increases the cost of these products thereby making them a great burden to low-income women.15 As of 2023, more than $150 million was generated by U.S. states annually from the tampon tax levied on menstrual products.33 The cost of menstrual products varies based on the type of product used. A menstruator may use 10 - 35 hygiene products per cycle which amounts to 16,800 products throughout their life-time.33 The average cost of these products is $7.21 per box of tampons,34 $6.45 per box of sanitary pads,33,35 $3.64 per box of liners,35 $20-$40 for a menstrual cup or disc,33,35 and $75 per pair of underwear designed to last for multiple years.33 Additional costs relating to period care can includes medications or heating pads.33 As of 2019, menstruators spent an average of $13.25 per month on menstrual products, and over the 40 year average that a woman menstruates, she spends a total of $6,000 before tax.26 According to Germano,36 “the average woman spends $120 each year on pads and tampons and an additional $20 each year on over-the-counter medication to combat cramps and other period-related side effects”. The work of Zi37 also decries the negative economic impact of a tampon tax. Despite this high cost of tampon/period products, many public assistance programs that support low-income women in the U.S. do not cover the cost of period products.7,38

The high cost of period supplies can mean that low-income women would prefer to purchase their basic necessities, such as groceries, as opposed to menstrual products7 because the high cost of period supplies affects the ability for low-income menstruators to afford them thereby increasing the vicious cycle of period poverty.26

The economic impact of COVID-19 pandemic on period poverty in the United States

The COVID-19 pandemic caused low- and middle-income women in the U.S. to become more vulnerable to period poverty because of the economic hardship it brought on them. The COVID-19 pandemic intensified the negative impact of period poverty on low-income and middle-income women in the U.S.7,26,39–41 COVID-19 led to deep inequalities in the U.S.'s economic, social, and health care systems, thereby putting women at more risk from the socio-economic devastation of the pandemic.39 COVID-19 brought about high unemployment, and this affected women negatively.19,38 Women who experienced income loss due to the impact of the pandemic struggled to afford/access period products7,16,19,26; they were 3.5 times more likely to experience period poverty than those who did not suffer an income loss.19,26 This situation became even worst for women who prior to the pandemic already had a low-income or had attained lower educational level because they were more vulnerable to struggling for access to period products during the pandemic.16,19,38 Considering that two-thirds of low-income women in the U.S. suffered of period poverty prior to the pandemic,7,40 the pandemic’s emergence created an even more deplorable condition that made women who had experienced income loss to be three times more likely to change their used menstrual health products (MHPs) less often or used MHPs to manage their period,19,26 such as the use of toilet paper41 an unhealthy product as MHP which can have devastating health impacts on women.

Social challenges of period poverty in the United States

This section addresses period poverty’s social impact within the scope of education, psychological, and health spheres. As discussed above, the lack of access to period products due to financial constraints is a pervasive issue in the U.S.42 This condition is highly correlated with depression and an overall poor quality of life, thereby leading to increased school absences for female students of menstruating ages and decreased participation in work and other activities for many low- and middle-income women.34,43–46 This condition significantly affects the health of women and girls of menstruating ages in diverse ways.

Educational challenges

Education is vital for society’s sustainability because it is through education that new ideas develop and innovations that bring about better and successful communities of enlightened people are made. Lower educational attainment puts women at a disadvantaged position for economic improvement.16,19,25 As indicated in Figure 1, period poverty leads to a decline in school attendance and performance,8,25 which leads to a vicious cycle that affects generations of low-income women.

A lack of effective education on menstruation contributes to period poverty in the U.S,26 and the implementation of menstrual health education in U.S. schools is very minimal.8,19,26 A 2022 study carried out in Midwestern U.S. middle schools shows that 79% of teenagers feel they need more in-depth education on menstruation to effectively deal with menarche experiences and the negative attitudes about body changes during menstruation.8 There is also no uniform curriculum across the states addressing menstrual education.26 Many states follow the National Sexuality Education Standards, but these do not include all the information needed since they lack important information on issues such as how to manage menstruation and personal care.26 Also, many U.S. states do not provide funding for period supplies in schools. Figure 221 shows the condition of period supplies across the U.S. with respect to funding by states.

Psychological challenges

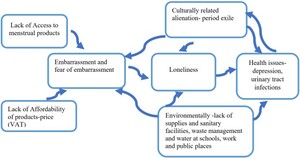

The psychological impact of period poverty can be seen in the negative impact it poses on the mental health of its victims and their sense of self and dignity. According to Carroll,40 period poverty “affects a woman’s sense of self, her sense of dignity and her ability to participate in life”. The inability to afford basic needs in itself affects individuals’ mental health.43,47,48 The mental health of victims of period poverty is affected due to regular isolation in order to avoid embarrassment, and this makes them psychologically unstable. Shoell49 posits that period poverty has a correlation with depression and anxiety among women by causing loneliness and the alienation of its victims (period exile); this creates a cumulative effect on the mental health of low-income women who are unable to afford period products because they feel very embarrassed.25 Figure 325 below shows how this takes place.

Health challenges

The inability to afford period products in itself can result in a mental health issue that may then produce different health conditions. Period poverty touches on the reproductive health of women because poor menstrual hygiene is associated with infections and a poor quality of life.8 Urinary tract infections, thrush, and other related infections caused by period poverty can pose a threat to women’s reproductive health. The numerous health challenges that are accompanied by period poverty may regenerate into reproductive health conditions that may hinder effective child delivery process or being unable to conceive.20

Political challenges to period poverty in the united states

The political desire of policy stakeholders in the U.S. at all levels of government to address period poverty is of great importance, but the lack of political willingness by elected officials limits their ability to make laws that can effectively address period poverty in the U.S.

There is only one law at the federal level that addresses menstrual equity, and that is the First Step Act that allows MHPs to be provided to women in federal prisons for free.41 It is unimaginable that a developed country like the U.S. does not have a holistic policy that address menstrual equity. Grace Meng, a congresswoman from Queens, New York, has repeatedly introduced a menstrual equity bill in the U.S. House of Representatives; this bill, which aims at addressing period poverty significantly in the U.S. by expanding access to free sanitary napkins and tampons (MHPs), has never passed16 neither has it been given appropriate attention by elected officials. The lack of political willingness to address this issue is reflected in this case.

The U.S. Congress currently has four bills that address period poverty, but at both state and federal levels, a total of 168 bills are in different legislative chambers.21 Most of these bills have not moved forward since they were sent to congressional committees and committees in other legislative chambers. This depicts the lack of support that period poverty (menstrual health related bills) gets from policy stakeholders in the U.S. from federal to local levels.

Many of the bills aimed at addressing MHPs die in legislative chambers at the federal and state levels without reaching a vote.41 Of the bills that are currently in the various legislative chambers in the U.S., most of those at the state level advocate for state funding for period supplies in public schools. Jaafar et al.15 state that policymakers in the U.S. have begun legislating at the state level to reduce period poverty, adopting a wide variety of different policy remedies.15 State governments most especially have much to do to broaden the scope of their policies to extensively address the problem of period poverty. Since the beginning of 2024, only 15 states in the U.S. have introduced, passed, or enacted bills in their legislative chambers, and most of the bills introduced have not gone beyond the introduction stage.50 For example, As of August 23, 2024, of the 58 bills in states’ legislative chambers, only 5 bills have been enacted whereas most of the remaining 53 bills have just been introduced or prefiled.50

The state of New York, like a few other states, is making gradual progress but more work still needs to be done. For example, due to the negative effect of period poverty, New York Assemblywoman Amy Paulin representing Assembly District 88 and New York State Senator, Michelle Hinchey representing the 41st Senate District introduced similar bills (A4060A and S5910B) to the New York Assembly and New York Senate on February 9, 2023, and March 22, 2023, respectively; these bills require that menstrual products be provided for free in all public college and university buildings to ensure easy accessibility.51 These bills took over a year to be passed in both houses after they were introduced. This is a similar situation in most states in the U.S. regarding this topic; that is, in cases where the bills are passed. Despite the delay, it is great to see that these bills have been passed in both houses and signed by the governor of New York. It should be noted that the scope of these bills will not provide period supplies to private colleges and universities in the state of New York. What happens to menstruating students and community members in these private colleges and universities? This is a question that needs to be answered by policymakers considering that U.S. citizens attend those private schools as well and they deserve to be taken care of by the state. It is based on issues like this that this study decries the need for holistic policies that can effectively serve the U.S. citizenry. Figure 451 shows the progress of the two bills in the two legislative chambers in New York state that have moved up to the stage when they were signed by the governor.

Cultural challenges of period poverty in the United States

Women’s experience of menstruation is tightly linked to the social and cultural values within their locality.2 In the U.S., the negative perception of menstruation characterizes the cultural context when girls begin menstruating.52 This affects the way most young girls view menstruation, and, for those who are unable to afford menstrual products, it becomes a great challenge for them to deal with. This cultural narrative has made some women to view menstruation as a secret, shameful, and undignified thing thereby making them unable to freely talk about it.52 Situations like this keep victims of period poverty away from sources that can assist them because they are unwilling to talk about their challenges due to societal perception about menstruation.

The role of family is crucial in shaping women’s perceptions about menstrual health, but some cultures view discussions about sex and menstrual education as taboo.2,8,52 Parents’ socio-cultural backgrounds can affect the way they relay sexual and menstrual health education to their children, and such parents can often act as a barrier to youth having sexual and menstrual health education.8 In the U.S. many parents deprive their children from having sexual education at an early stage; in fact, 87% of American high schools allow parents to opt their children out of sex-ed classes.8 Due to this situation, most teenagers prefer the education they receive from their mothers and siblings than the one they receive from school.8

Contraceptive pills that help to delay menstruation also reflects the negative culture of menstruation,2,52 and in the U.S., so many pharmaceutical industries are at the forefront of promoting these pills.52 The political culture in the U.S. is not menstrual friendly considering that issues that deal with period poverty have not occupied the core unit (decision agenda) of the policy agenda from the federal to local levels.

Efforts made to address period poverty in the United States

Efforts are being made at the federal, state, and local levels to address problems associated with period poverty despite the challenges. For example, congresswoman Grace Meng’s “Menstrual Equity for All Act” bill that has been introduced in the U.S. Congress16,21 overtime with continuous failure is beginning to gain support from other elected Congressional officials to engage and address the problems associated with period poverty. Congressmen Sean Casten and Al Green have recently joined efforts to initiate bills addressing period poverty in the U.S. by introducing menstrual health bills in the U.S. Congress.21 The emergence of COVID-19 brought about the passage of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) by the U.S. Congress which among other supports, provides financial relief to enable people to use pre-tax dollars to buy MHPs.41

Since 2018, several states have made efforts to provide free MHPs in public schools.41,51,53 As of July 16, 2024, a total of 24 states in the U.S. provide free MHPs to public schools in the U.S.21 The map in Figure 550 below shows menstrual health related bills that have been introduced/passed/enacted in the U.S. in 2024 at states’ legislative chambers to address the safety, accessibility, or affordability of menstrual care products.

From the map, California, Oklahoma, Kansas, Iowa, Minnesota, Illinois, Kentucky, Ohio, Georgia, South Carolina, Vermont, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, and Hawaii are the states that have introduced/passed/enacted bills that address safety, accessibility or affordability of menstrual care products as of July 2024.50 These states respectively have the following number of bills 2, 4, 1, 3, 3, 5, 1, 2, 5, 7, 3, 2, 3, 8, and 9 that have been introduced, passed, or enacted in their legislative chambers.50

Implications for policy

Policy stakeholders at all levels in the U.S. must show the political willingness to address the problem of period poverty and do so effectively in a sustainable manner. They should do this by making policies that close inequality to access period products.

Sexual education with a well-structured curriculum in schools should be implemented where students, most especially female students, attend and learn about important things that relate to sexuality, gender, and menstrual education at an early stage so that can be well prepared for menarche and related issues at an early age. This will help overcome any stigma or other cultural barriers regarding menstruation.

All states should remove tampon taxes on period products. The issue is not just to remove taxes on period products; the most important thing to do is to create an avenue where period products can be accessed by women and girls of menstruating ages for free.

Period products should be made available for free in all public places. Government at all levels and non-governmental organizations should work together to facilitate the provision of free menstrual products in public places, not just in public schools and prisons, as it has been in most cases.

CONCLUSIONS

Period poverty is a problem that is embedded in the U.S. fabric. It is addressed in this study within the spheres of economic, social, political, and cultural challenges. The devastating effects of period poverty on the health of women, most especially low-income women, cannot be overemphasized. Women who suffer of period poverty are exposed to health challenges that can affect their reproductive system, among other challenges. These women are also very likely to have poor academic performance due to absenteeism from classes which may even lead to becoming a school dropout thereby making them unable to effectively contribute to the wealth of the nation and provide for their basic needs. Under such conditions, these women are exposed to psychological challenges that can affect their mental health. The lack of political willingness by policy makers to get this problem solved is the main reason why it remains an issue in the U.S. Bills that aim to address period poverty are introduced in legislative chambers at various levels of government, but elected officials are not committed to vote for most of these bills. For those that succeed in passing in legislative chambers, they possess a limited scope considering that they do not address issues of public interest from a holistic perspective.

The cultural attitude about periods in the U.S. also contributes to period poverty in the country because menstruation is accompanied by societal stigma, and this makes some menstruating women to feel ashamed causing them to not seek sources that provide them access to period products. Notwithstanding the challenges of period poverty in the U.S., policy stakeholders are gradually paying more attention to menstrual health related issues.

Funding

None.

Authorship

BGA is the sole author.

Competing interests

The author completed the ICMJE Disclosure of Interest Form (available upon request from the corresponding author) and disclose no relevant interests