Medical supplies that are unused or nearing expiration in hospitals are routinely discarded in the United States. Due to strict hospital policies and regulations, these medical items are no longer fit for patient use. An estimated $200 million in prepared supplies are discarded unused in operating rooms in the United States each year1. During surgical cases, supplies may be prepared and kept ready for procedures yet often go unused by the end of the case. Although these surgical supplies are still suitable for subsequent use, they are typically labelled for disposal. However, it is well-known that these supplies are safe to use and can be redistributed abroad to relieve the burden on donor hospitals and provide health services to those in need.

Ndogbati Protestant Hospital in Douala, Cameroon, a critical access facility facing challenges in providing consistent patient care due to inadequate infrastructure and lack of access to essential medical equipment. Like many healthcare institutions in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), the hospital often relies on external donations to provide basic diagnostic and treatment capabilities 2–9. Healthcare facilities in Cameroon have trained personnel but often lack the proper equipment and supplies necessary to provide standard patient care 10. They often depend on donated medical supplies from foreign institutions to acquire or replace diagnostic equipment. The Body Screening Project Medical Equipment Donation (BSPMED) program involves collecting and redistributing clean, unused medical supplies that would otherwise be discarded to healthcare institutions in developing nations. The World Health Organization (WHO) stresses that medical donations should be directed to recipients who genuinely need the equipment and have the proficiency to operate and maintain it 11. Although donations are provided to strengthen beneficiary facilities’ healthcare delivery, donors often fail to consider the contextual challenges of receiving donations and translating them into improved health outcomes, such as stable access to internet, electricity, and purified water 12.

Despite the WHO’s recommendations for the donation of medical supplies, donors rarely follow these guidelines 7. There is limited use of surveys to assess the impact of medical donations to healthcare facilities in LMICs. Furthermore, the perspectives of hospital staff regarding the usability and integration challenges of the donated equipment on their ability to deliver patient care effectively, remain largely unexplored.

This study evaluated the effectiveness of a medical supply donation program in addressing local needs and patient care outcomes. It included systemic and logistical factors and barriers to successfully integrating donated items into the hospital’s workflow.

METHODS

Materials and Procedures

Donated medical supplies were sourced from Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center and SHARE (Supporting Hospitals Abroad with Resources and Equipment) at Johns Hopkins. The selection of supplies was informed by the experiences of The Body Screening Project (BSP) in Cameroon, which identified deficiencies in local hospitals. In April 2024, Ndogbati Protestant Hospital in Douala was chosen due to resource constraints and limited access to overseas donations. Medical equipment including diagnostic devices, that did not require electricity or internet were preferentially selected to ensure suitability for the hospital’s context. Supplies valued at $5,600 were inspected, sorted, and transported to Cameroon in accordance with the World Health Organization’s guidelines on medical device donations 8.

The donation process involved multiple steps to ensure the suitability and usability of items. These included careful sorting of supplies based on the specific needs of the recipient hospital and rigorous inspections to confirm that all donated items met international safety standards. Following this, the supplies were inventoried, packaged, and shipped. A formal donation ceremony, held in partnership with the Evangelical Church of Cameroon (EEC), Center for Diseases of the Digestive Tract (CMAD), and Johns Hopkins Medicine, provided an opportunity to publicly hand over the supplies to hospital leadership and reinforce the collaborative nature of the initiative. However, no formal training on using the donated equipment was provided, highlighting a critical gap that warrants attention in future programs. Without proper training, the potential benefits of donated supplies could be significantly reduced, leading to underutilization, incorrect usage and possibly compromising patient care.

Setting

Ndogbati Protestant Hospital is in Douala, Cameroon, and serves as a critical healthcare facility for approximately 14,000 patients annually. The hospital has three departments: Administrative and Support (Administration, Other), Clinical Services (General Surgery, Obstetrics-Gynecology, Pediatrics, Primary Care), and Laboratory. However, frequent disruptions in electricity and water supply significantly hinder the delivery of consistent and effective healthcare services. These operational challenges highlight the critical need for medical equipment that is compatible with the hospital’s infrastructure and can function reliably in low-resource settings.

Survey Design and Data Collection

A post-donation survey, administered via REDCap six months after the donation to allow for equipment utilization, was designed and conducted among hospital staff. A convenience sampling strategy was employed to survey available hospital staff members at Ndogbati Protestant Hospital. The survey instrument was designed to collect perspectives on the donation process, usability of donated supplies, and the impact on healthcare delivery. It combined quantitative and qualitative questions from open-ended questions to ensure a comprehensive evaluation. Key areas covered included hospital demographics and roles (Q6, Q7), barriers to effective utilization of donations (Q8, Q9), equipment utilization rates and reasons for non-utilization (Q12, Q13, Q18), satisfaction with the condition and utility of donated equipment (Q14–Q16), training requirements and integration challenges (Q19, Q20), and the overall impact on patient care (Q21). We also asked participants to identify future equipment needs and provide suggestions for improving the donation program (Q22, Q23). A full list of self-administered survey questions is in the Online Supplementary Document, Appendix A.

Analysis

This study employed a mixed-methods approach, integrating both quantitative and qualitative analysis of survey data. Descriptive statistics were applied to summarize key variables, providing an overview of respondent characteristics, barriers encountered, equipment utilization rates, satisfaction levels, and the perceived impact on healthcare delivery. We stratified results by department to identify patterns and differences across hospital roles, highlighting variations in experiences and needs. Bivariate analyses, including Chi-Square test or Fisher’s exact test, were conducted to compare results across categories. Data were analyzed with R version 4.4.2 (02-12-2024).

Thematic coding of qualitative responses identified recurring patterns and actionable insights. We extracted themes such as training needs, logistical challenges, equipment suitability, and future needs to provide deeper context for the quantitative findings. Findings were reported and presented in bar charts, pie charts, and word clouds to highlight key trends and enhance data interpretability.

Ethics

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. It was approved by the Ndogbati Protestant Hospital and The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine with reference number IRB00458270. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before they participated in the study.

RESULTS

Respondent Characteristics

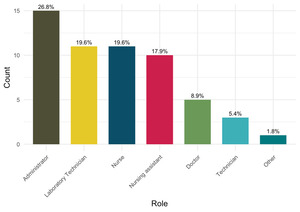

A total of 59 completed responses were obtained from a total estimated 68 eligible hospital staff members, representing a response rate of 86.8%. The survey included a diverse range of respondents at Ndogbati Protestant Hospital. The more significant proportion of respondents belonged to Clinical Services (50.8%), followed by Laboratory staff (30.5%) and Administrative and Support staff (18.6%) (Figure 1). In terms of roles, administrators constituted the highest share (26.8%), followed by laboratory technicians (19.6%) and nurses (19.6%). A smaller proportion came from doctors (8.9%) and other hospital roles (Figure 2). This distribution ensured a comprehensive representation across the hospital.

Barriers and System Challenges

Regarding the barriers the hospital faces (Table 1), cost was the most significant, reported by 67.6% of respondents. Personnel shortages (13.2%), supply chain issues (11.8%), and corruption (7.4%) were also highlighted, although less frequently. These challenges were consistent across departments, with cost being the most dominant factor in Administrative and Support (89%), Clinical Services (67%), and Laboratory (91%) staff responses.

Hospital’s Infrastructure and Needs

Nearly all respondents (96.4%) reported that the hospital lacked an established transportation system for receiving overseas donations, indicating a critical gap in the infrastructure needed to facilitate efficient delivery. Despite this, 59.3% of respondents rated the donation drop-off process as “very easy” (Figure 3).

Regarding the preferred frequency of donations, nearly half of respondents (46.4%) preferred donations to occur every three months. Other preferences included “as needed” (19.6%), “once per year” (17.9%), and “every six months” (16.1%). Overall, respondents favored frequent and regular donations to meet the hospital’s needs (Online Supplementary Document, Figure S1).

Donated Materials and Condition

The condition of the donated equipment was assessed upon arrival (Table 2). These findings indicate high satisfaction with the quality of donated equipment.

Setup of Donated Equipment and Putting it into Use

Training Requirements for Equipment Operation

Overall, 30% of respondents reported the need for additional training to operate the donated equipment effectively. This response was most common in the Administrative and Support department (33%), followed by Clinical Services (30%) and Laboratory (27%).

The open-ended responses to the question, “Please specify what training was needed and how it was provided,” revealed two key themes. First, respondents highlighted the need for refresher training or upskilling, referred to as “recyclage,” with frequent mentions of general skill updates across roles. For example: “Recyclage général” (general upskilling), “En tout donc un recyclage général” (in summary, a general refresher training). Second, language barriers were challenging, particularly concerning unfamiliar languages in manuals and training materials. These findings underline the need for tailored training programs, including regular upskilling sessions and multilingual resources, to improve the utility of donated equipment across all departments.

Challenges in Integrating Donated Equipment

Integration of the donated equipment into existing workflows was reported as seamless by 64.3% of respondents, who encountered no challenges (Online Supplementary Document, Figure S2).

Utilization of Donations

Overall, the analysis of donation usage revealed that a significant proportion (43%) of respondents reported utilizing 76–100% of the donations, followed by 30% who utilized 51–75%. Only a small percentage of respondents (3.6%) reported using less than 10% of the donations. Conversely, 33% of respondents indicated that 10–25% of the donations were unused, and 27% reported less than 10% of the donations being unused (Online Supplementary Document, Figure S3).

Helpfulness and Need Fulfilment

Most respondents (55.4%) rated the donated medical supplies as “very helpful” in providing patient care, while 41.1% rated them as “somewhat helpful.” Stratification by department revealed significant differences (p = 0.023) (Table 3). Differences across departments were not statistically significant (p = 0.224).

Impact on Patient Care

The direct impact of donated medical supplies on patient care was distributed across varying levels. Most respondents (33.9%) reported a minor impact, while 30.5% indicated a moderate impact. Some respondents reported either a significant impact (23.7%) or no impact (11.9%) (Online Supplementary Document, Figure S4). Stratification by department revealed no statistically significant differences (p = 0.274) (Online Supplementary Document, Table S1).

Future Donation Needs

Most respondents identified diagnostic equipment (83.1%) as a critical need, followed closely by treatment (83.1%), surgical (83.1%), and monitoring equipment (81.4%). The need for other equipment was comparatively lower, reported by 16.9% of respondents. Significant differences were observed only for diagnostic equipment (p = 0.044), indicating a particularly high demand in some departments (Online Supplementary Document, Table S2).

Thematic analysis of feedback regarding future needs identified several key areas of focus: training requirements, critical equipment gaps, logistical challenges, and positive sentiments toward the donation program (Online Supplementary Document, Figure S5**). Below is a detailed exploration of each theme.

Training

A recurring theme was the need for targeted training and upskilling to utilize donated equipment effectively. Many respondents emphasized the importance of structured programs to address gaps in knowledge and skills. For example, one respondent highlighted the need for “ambulance driver training and upskilling,” while another stressed “training and retraining” as priorities. Such insights suggest that future donations should incorporate consistent and tailored training initiatives to empower staff and maximize the benefits of the donated resources.

Critical Equipment Gaps

Many responses focused on equipment gaps and infrastructure deficiencies that hindered effective healthcare delivery. High-priority items included ambulances, described as “vital,” and morgues, frequently mentioned as essential. Specialized pediatric equipment, such as incubators, radiant warmers, and phototherapy devices, was also identified as critical for improving patient care. Additionally, respondents pointed to an urgent need for infrastructure upgrades, including renovating dilapidated buildings and replacing outdated facilities. One participant noted that “Renovation of dilapidated buildings and purchase of an ambulance” were crucial. Addressing these equipment and infrastructure gaps should be a central focus for future donations to enhance the operational capacity of recipient institutions.

Logistical Challenges

Feedback highlighted logistical challenges that limit full utilization of donations. A significant issue was the lack of coordination and communication between donor organizations and recipient institutions. One respondent commented, “To improve communication and coordination between our institutions for future donations, it is essential and crucial to establish and consider the expectations of each institution with respect to the other.” Operational inefficiencies, such as staff shortages and the absence of essential medical devices, further complicate the integration of donated resources. These findings underscore the need for strategic planning and enhanced communication channels to align donations with institutional needs and capabilities.

Positive Sentiments

Despite the challenges, there was widespread positive sentiment towards the donation program. Many participants expressed gratitude and optimism, describing the initiative as a “very good program” and acknowledging its benefits to their institutions. One respondent noted, “We appreciate this partnership. Support for staff in recycling and upskilling training would also be welcome.” Such feedback highlights the program’s potential to make a meaningful impact and to serve as a strong foundation for fostering relationships with donors and encouraging further support.

DISCUSSION

Interpretation

The study highlights the successes and challenges of the medical supply donation program at Ndogbati Protestant Hospital, providing valuable insights into its effectiveness, systemic and logistical barriers, and alignment with operational needs. The program demonstrated a meaningful impact on addressing hospital needs and improving patient care outcomes. Although most respondents found the donation drop-off process “very easy” (59.3%), the logistical gaps reported by others underscore the need for a more robust infrastructure to facilitate equitable access and ease of use. These challenges highlight the importance of addressing systemic constraints to ensure consistent benefits across all departments. The variation in utilization across departments reflects gaps in aligning donations with the hospital’s specific operational requirements. While the program effectively addressed some needs, a more tailored approach to donation planning is necessary to optimize alignment and impact.

Comparison with Similar Programs

The findings align with challenges commonly reported in medical supply donation programs in low-income settings. Literature emphasizes the importance of aligning donations with recipient needs, infrastructure, and skill levels to maximize utility and impact. Programs that fail to involve recipients in planning or adhere to established guidelines, such as the World Health Organization donation framework, often encounter underutilization issues, as seen in this evaluation.

For example, a survey of clinical engineering effectiveness in developing world hospitals across 43 low-income and middle-income countries revealed that up to a third of all donations occurred without prior consultation13. A review of the literature and guidelines for surgery and anesthesia in low-income and middle-income countries, published in BMJ Global Health, highlights the complexities of medical equipment donation in low-resourced settings 14. This study stresses the importance of “equitable partnerships, consultation of policies and guidelines, and careful planning” to improve equipment usability and lifespan 15. This strongly correlates with our findings of underutilization due to compatibility and training gaps.

A study published by Bauserman et al. (2015) conducted in a rural clinic evaluated the utility and durability of donated medical equipment, providing real-world examples of items that were used or were not used 15. It also showed that training was a factor in equipment use, even with donated equipment. This reinforces our findings related to the necessity of training.

Additional studies reinforce the importance of needs-based assessments, logistical support, training, and sustainability in medical supply donation programs ^[16-19]. For instance, Emmerling et al. (2017) found in their study in Rwanda that a significant portion of donated equipment remained unused due to lack of training 16, a finding that aligns with our observation of underutilization for similar reasons. Similarly, Ojo and Waheed (2024) emphasized that donations should be aligned with the local health system’s priorities and capacity rather than donor-driven ^[19], which supports commendations for needs-based donation strategies. The challenges observed at Ndogbati Protestant Hospital are not isolated incidents but reflect broader systemic issues that require careful attention and a shift toward recipient-centric approaches.

Study Limitations

This study had several limitations. The focus on a single facility restricts the generalizability of findings to other healthcare facilities. The organizational culture of Ndogbati Hospital may differ significantly from other institutions, even within Cameroon or other LMICs. Therefore, the impact and challenges observed may not be directly transferable to hospitals with different patient demographics or operational structures.

The reliance on self-reported survey data introduces the potential for response biases. For instance, respondents may have underreported issues such as corruption or dissatisfaction due to social desirability bias, in an effort to present the hospital in a more positive light. Additionally, the absence of longitudinal data is a significant limitation. Our post-donation survey only provides a snapshot of the impact at a single point in time. Without follow up data, the ability to evaluate the long-term impact of the donation program on patient outcomes and hospital operations is limited. Lastly, due to resources and time constraints inherent in conducting research in this context, post donation survey was not formally pilot-tested prior to implementation. This lack of pilot testing may have impacted on the clarity and comprehensibility of certain questions. Addressing these limitations through future research, such as conducting multi-site studies, employing longitudinal data collection tools, integrating objective assessments of equipment utilization and patient outcomes, would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the program’s effectiveness and sustainability.

Implications for Practice

The findings of this evaluation have significant implications for the planning and implementation of future donation programs. Addressing the identified barriers and leveraging the program’s strengths can lead to more effective and sustainable outcomes.

Training and Capacity Building: Tailored training programs are essential for maximizing the utility of donated supplies. This evaluation revealed a clear need for department-specific training to address gaps in knowledge and ensure that equipment is used effectively. Providing refresher courses or “recyclage” was a recurring theme in the qualitative feedback.

Alignment with Recipient Needs: The variation in utilization and satisfaction across departments underscores the need for donor programs to engage recipients during the planning phase. Conducting needs assessments and involving hospital staff in decision-making can help align donations with actual requirements, reducing underutilization and dissatisfaction.

Sustainability and Monitoring: Regular evaluations and feedback loops are essential for refining donation strategies over time. Establishing metrics to monitor the utilization and impact of donations can help identify and address emerging challenges, ensuring that resources are used optimally.

Recommendations

Based on the findings from this study, the following recommendations are proposed to address identified challenges and enhance the effectiveness and sustainability of the medical supply donation program.

Addressing Barriers

Cost Mitigation: Develop a financial support framework to assist hospitals in covering costs related to transportation, storage, and integration of donated supplies. Collaboration with government agencies or private donors to subsidize these costs can alleviate the financial burden on recipient hospitals.

Logistics Infrastructure: Establish reliable transportation systems tailored to low-resource settings. For example, creating partnerships with local logistics providers or non-governmental organizations (NGOs) can help build an efficient supply chain to ensure the timely delivery of donations, especially in remote areas.

Enhancing Utilization

Needs-Based Donations: Conduct thorough needs assessments before donations, involving recipient hospitals in the decision-making process to align supplies with actual operational needs. This step can significantly reduce underutilization and improve satisfaction.

Training and Skill Building: Implement tailored, department-specific training programs for hospital staff to maximize the use of donated equipment. This includes refresher courses (“recyclage”) and multilingual training materials to address language barriers noted in the feedback.

Equipment Compatibility: Ensure that donated equipment matches recipient facilities’ infrastructure and resource capacities. For instance, providing diagnostic tools not reliant upon stable electricity or internet is essential for hospitals like Ndogbati Protestant Hospital.

Sustaining Impact

Maintenance Support: Include a maintenance framework in the donation process, ensuring access to spare parts, repair services, and technical support for donated equipment. Establishing partnerships with local technicians can provide sustainable solutions for upkeep.

Recurring Evaluations: Conduct regular follow-ups to assess donations’ utilization, recipient satisfaction, and impact over time. These evaluations can identify emerging issues and inform adjustments to future donation strategies.

Infrastructure Upgrades: In parallel with equipment donations, consider supporting critical infrastructure improvements such as power stability, water access, and facility renovations. Addressing these systemic barriers can enhance the overall effectiveness of donations.

Future Donation Strategies

Regular Donation Cycles: Based on the findings, most respondents preferred quarterly or “as needed” donation cycles. Programs should establish predictable schedules while maintaining flexibility to respond to urgent needs.

Focus on High-Demand Items: Prioritize providing high-demand equipment, such as diagnostic, surgical, and monitoring tools, as identified in the evaluation. Addressing specialized needs like pediatric equipment and laboratory devices can significantly improve patient care outcomes.

Stakeholder Collaboration: Foster stronger partnerships between donors, recipients, and local organizations to enhance communication and coordination. Establishing donor-recipient agreements can clarify responsibilities and expectations for using and maintaining donated equipment.

Strategic Planning and Advocacy

Policy Advocacy: Advocate for policies that facilitate donations, such as reduced customs fees for medical supplies and expedited processing for donations in low-income settings.

Capacity-Building Partnerships: Collaborate with educational institutions or NGOs to offer capacity-building initiatives, including technical training and infrastructure development.

Local Empowerment: Encourage the involvement of local communities and hospital staff in planning and decision-making to build ownership and ensure that donations address context-specific challenges effectively.

CONCLUSIONS

This evaluation of the medical supply donation program at Ndogbati Protestant Hospital highlights its contributions to addressing hospital needs and improving patient care, with most respondents finding the equipment good quality and useful. However, systemic and logistical challenges, including cost constraints, lack of transportation infrastructure, and insufficient training, limited the full utilization of donations.

Aligning donations with operational requirements remains critical. The laboratory department expressed lower satisfaction, underscoring the need for compatibility with infrastructure and skill levels. Targeted training, particularly department-specific refresher courses and localized materials, are essential to overcoming barriers.

Ultimately, maximizing the impact of medical equipment donation requires a truly collaborative approach. To enhance sustainability, the focus should shift from simply sending supplies deemed useful to prioritizing needs-based donations, complemented by necessary training, robust logistical support, and ongoing monitoring. Addressing these challenges can maximize the effectiveness of donation programs and strengthen healthcare systems in resource-constrained settings.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Ndogbati Protestant Hospital staff for their participation, and the Evangelical Church of Cameroon (EEC), The American Osteopathic Foundation, and Johns Hopkins School of Medicine for their support in the donation process.

Data availability

The fully anonymized data set supporting this study’s findings is available upon request. Requests for access to the data should be directed to the corresponding author.

Funding Statement

The AOF’s International Humanitarian Medical Outreach Grant and Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center Rajiv Thakkar Scholarship supported this initiative to provide free medical supplies to Ndogbati Protestant Hospital.

Author Contributions

-

Emmanuel Tito: Conceptualization (lead); Methodology (lead); Funding acquisition (lead); Project administration (lead); Writing – review & editing (lead).

-

Etienne Ngeh Ngeh: Methodology (supporting); Data curation (supporting); Writing – review & editing (equal).

-

Ines Kafando: Investigation (supporting); Formal analysis (supporting); Writing – review & editing (equal).

-

Fatima Halilu: Methodology (supporting); Writing – review & editing (equal).

-

Ope Olayinka: Writing – original draft (supporting); Validation (equal); Writing – review & editing (equal).

-

Oriane Taku: Writing – review & editing (equal); Data curation (equal); Project administration (equal).

-

Saanvi Dixit: Methodology (supporting); Writing – review & editing (equal)

-

Anita Tito: Project administration (lead); Resources (lead); Supervision (supporting).

-

Peter Ebasone: Methodology (equal); Data curation (lead); Formal analysis (lead); Software (lead); Writing – review & editing (equal).

Competing Interests

The authors completed the ICMJE Disclosure of Interest Form (available upon request from the corresponding author) and disclose no relevant interests

Additional material

This manuscript contains additional information as an Online Supplementary Document.

Corresponding Author

Emmanuel Tito, DO

Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Internal Medicine Department

5200 Eastern Avenue, Room 260

Mason F Lord Building

Baltimore, MD 21204

United States of America

Tel: (410) 550-0926

Fax: (410) 550-1069

E-mail: etito1@jh.edu