INTRODUCTION

Within and across national boundaries, rural residents generally have poorer health outcomes compared to urban dwellers.1,2 Access to care and services is a major issue facing rural communities in the Global South – and this includes challenges with service delivery, workforce resourcing, governance, transportation, and communication.1,2 To meet the needs of rural populations, we must first identify the types of unmet health needs to plan appropriate and effective programmes for improving and initiating new services.3–5 Health needs assessments (HNAs) are an essential tool for this purpose. They use a systematic approach to gather information, determine the unmet needs of a population, and match them to services.6–8 Outputs from HNAs are used to provide a baseline understanding of communities’ health, as a resource for prioritising and planning services (including writing grant applications for research), and to guide comprehensive health promotion strategies.5

HNAs in rural communities are especially critical as they lack attention, and there is limited routine data on the utilisation of existing services. There is growing emphasis from the international community and academia that well-conducted HNAs should go beyond healthcare services and be holistic in considering not just the biological but also the psychosocial aspects of health, and integrate participatory approaches that involve community members in HNAs from the planning to the implementation and evaluation stages.5 Beyond service provision, social determinants and environmental factors are also important as rural communities may lack basic infrastructure and suffer from greater health inequities compared to their urban counterparts. Well conducted rural HNAs account for these factors such as: sanitation, employment opportunities, and other social determinants.9,10

HNAs are often conducted by local health units or academics, which translate to communities having fewer barriers to entry for organisations keen to provide health services to meet rural health needs. However, neglected rural communities that have limited support are unknown to organisations keen to supply services. Otherwise even when they are known, in the absence of HNAs, assumptions are made in developing services perceived to be useful instead of what actually is.5 There is an imperative to provide a universal profile that organisations can use as a guide to design and supply services to rural communities, in a hope that rural access to care will increase with this knowledge. Similar projects have been attempted, such as the Healthy People initiative in the United States which conducts national HNAs to identify nationwide health improvement priorities – and this is repeated regularly to track changes over time.10,11 Specifically Rural Healthy People 2020 was conducted between 2010-2012 to provide consensus on national rural priorities to serve as a guide for action by stakeholders to improve health of rural communities across the United States.10

Compounding the health inequities in rural communities, is the inequity in access to care in the Global South.12 Rural communities in the Global South have poorer access to care due to geographic and financial inaccessibility, and poor quality and acceptability of available services.13 Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa share a significant proportion of countries in the Global South. Although they are collectively home to 90% of the world’s rural population, there are no large-scale studies that can provide broad priorities to guide organisations to supply services to rural communities in these regions.14 There are several rural HNAs conducted in Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa for the purposes of making decisions on commissioning specific services, but few that conduct a ‘holistic ground-up’ needs assessment to map out a community’s needs for any or all services. A literature review of community-level rural HNAs in the past ten years revealed that a number of holistic ground-up needs assessments were conducted in the United States, whilst only a handful were conducted in Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa (e.g. in Kenya, Vietnam, and various states in India).3,7–9

Our objective is to take a macrosystem perspective of rural needs by painting a universal understanding of rural health needs in Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa to reduce barriers to entry, and attract organisations to supply services, to further improve access to care in these regions. With this objective in mind, this study sought to answer two fundamental questions:

-

What needs do rural residents in Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa have?

-

Do needs for rural residents in Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa differ within and across national boundaries?

METHODS

Approach

This assessment utilises a traditional top-down epidemiological approach to health needs assessment that was designed and planned by the team.6,8 Although our top-down approach has its limitations, we saw it as an appropriate starting point for rural community needs assessments at a regional scale as there have been no other published assessments that were approached with the same macrosystem perspective. We balanced our top-down approach to assessment with community participation in designing the HNA tool (which is described below in further detail). We focused on collecting felt needs – as defined in Bradshaw’s taxonomy.15 Felt needs recognise that direct subjective experiences of people are important, especially in rural communities who are at a disadvantage and for which experts have limited knowledge on.16 We mitigated limitations of assessing felt needs by designing the needs assessment in a structured way. ‘Needs’ in our study are interpreted as having the capacity to benefit from existing services – providing practical approaches to meet needs.6 Therefore, we limited our assessment to a multiple-choice question which asked residents to express their interest in specific services that the team assessed to be essential to rural communities.

Data Collection

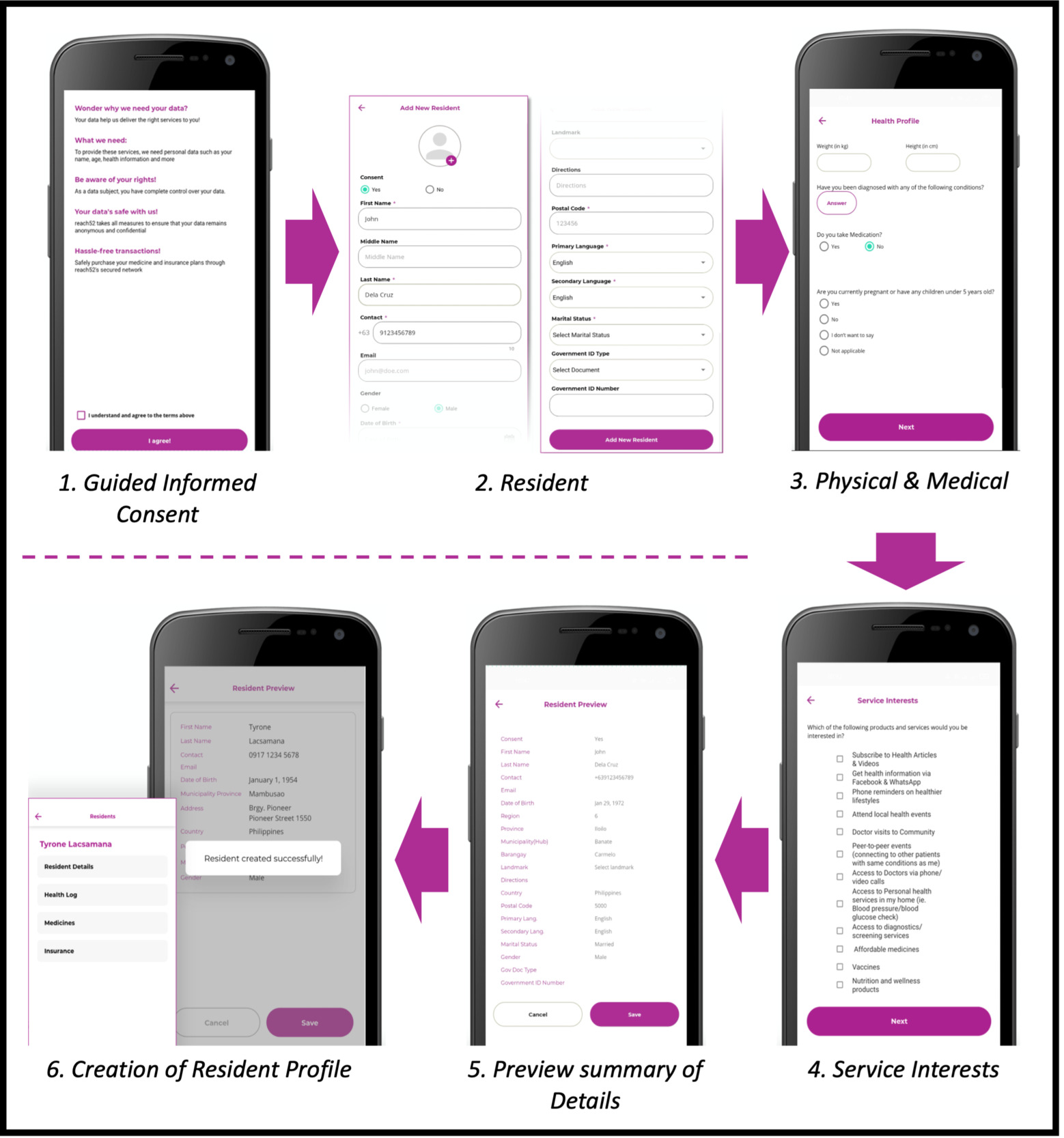

Data was collected by reach52 – an organisation working across Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa with the aim of improving access to care for rural communities and achieve social impact through sustainable solutions. Data was collected after obtaining informed consent from all participants through a standardised script (Figure 1). The data used in this study was collected using a pre-signup questionnaire that is administered to all participants.

Unified Digital Platform

Resident data on explanatory and outcome variables were collected using a unified digital platform (Figure 1). The integration of resident data to a single platform across the organisation’s regional operations enabled research through seamless data extraction and standardised analysis. The platform design and technical changes are managed by an international product management and engineering team to ensure that processes are standardised across all localities, and the platform interface is translated into the languages appropriate to each community with the help of local team members. Visual screenshots of the digital platform interface are shared in supplementary file 2.

Training for Surveyors (Community Health Workers)

Data was collected by trained community health workers (CHWs) situated within each locality of operations in collaboration with local partners. CHWs are well-positioned to act as intermediaries between communities and providers as they understand socio-cultural norms and have the potential to increase access to care in rural communities.17 The reach52 model of care trains new and upskills existing CHWs as empowered members of the community to engage residents enrolled under their care to achieve intended health outcomes. This is achieved through a standardised training curriculum with local adjustments that ensure CHWs are competent and consistent but also adapted to meet local cultural and contextual challenges.

To ensure standardisation of data collection across the localities, the core standardised set of skills are taught to all CHWs. The training materials are translated into the languages appropriate to each community and adjusted for the local context with the help of local team members, invited consultants, and partners. This core training involves their primary role and responsibilities as a CHW, how to collect information from residents, how to provide continuous community support, rapport building and communication skills, navigating socio-cultural dynamics, and understanding cultural sensitivity and respectfulness. CHWs are trained to use the digital platform to enter and manage data and access real-time health information on their enrolled residents. To avoid disruptions to their operations in areas of poor internet connectivity, CHWs are also trained to ensure offline functionality of the digital platform and troubleshoot common digital platform technical and performance issues.

The training programme includes assessments to ensure the knowledge is internalised. Additionally, reach52 conducts regular performance evaluations and target setting, bi-monthly monitoring calls, and provides individualised feedback to CHWs through the country offices to maintain their effectiveness. CHWs also have access to regularly updated training modules that enable continuous upskilling and knowledge retention throughout their career.

Data Protection

Data extracted for this study was initially collected for operational purposes, but the processes are upheld to the highest ethical standards. Data protection is governed by the organisation’s data protection policy which incorporates seven guiding principles:

-

Lawfulness, fairness and transparency;

-

Purpose limitation;

-

Data minimisation;

-

Accuracy;

-

Storage limitation;

-

Integrity and confidentiality; and

-

Responsible for demonstrating compliance with national regulations.

A global data protection officer based in the Philippines is accountable for the data protection policy. Interventions to ensure compliance to the policy standards include information governance training for all staff, clear lines of reporting and supervision for compliance with data protection, monitoring by data protection officers, regular internal and external independent audits, and reminder bulletins for staff.

Importantly, CHWs are taught data privacy principles, emphasising transparency, informed consent, and the secure handling of personal and health information in the field and within the digital platform. To ensure privacy of participant data, they are taught the process of obtaining informed consent when engaging residents and collecting their data and the principles of data security (best practices for using passwords and two-factor authentication).

Data Management and Storage

Data extracted for this study is hosted in MongoDB Atlas and Amazon Web Services Mumbai (except for Indonesian data which is housed in-country in Jakarta). The data is stored securely using MongoDB Atlas encryption and is subject to strict authorisation policies. The extracted data is stored on a single research investigator’s device under encryption. The data contains unique resident identification numbers assigned by the organisation but does not contain personal identifiable information such as names, national identification numbers, or street addresses to maintain personal data security.

Sampling

The data was collected by convenience sampling. Rural residents that reach52 engaged across the Global South between July 2022 to October 2023 for various health campaigns were provided a pre-signup questionnaire. During this period, reach52 had a presence in several countries across Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. All residents who agreed to join the health campaign and fill in the pre-signup questionnaire were recruited into this study. The period for extraction was limited to the period after which the digital platform and CHW training had been standardised across all regional operations, and to avoid collecting data over prolonged periods of time which could be influenced by contextual events (e.g. epidemics, natural disasters). Data was extracted from communities in five countries across Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa that reach52 had engaged with between July 2022 to October 2023: India, Philippines, Indonesia, Cambodia, Kenya, and South Africa. Data from these countries were collected from a few localities, as shown in Figure 2.

Variables

Data was self-reported by residents and collected via the pre-signup questionnaire with the assistance of CHWs (Figure 1). The outcome of interest was the question: “which of the following products and services would you be interested in” (see Figure 1). Residents could pick multiple options, not pick any, or respond with an “I don’t know” or “refused” option. Because data was collected at baseline, no interventions had been carried out at the time of data entry. Although a top-down epidemiological approach was used for the HNA (as explained above), participatory approaches were adapted to develop the list of 13 services available for selection. The services were selected by reach52 through consultation with local team members across multiple sites, and these include: “health articles I can read myself”, “health information through Facebook or WhatsApp”, “Phone reminders for a healthier lifestyle”, “local health events”, “physician services”, “diagnostic / screening services”, “nutrition or wellness products”, “consumer health products”, “consumer non-prescription medications”, “affordable medicines”, “vaccines”, “connecting with other patients with the same condition as me”, and “home personal health services”. The interface for data entry is shared in supplementary file 2.

For this study, demographic explanatory variables analysed include age, gender, employment, household income, height, weight, and presence of significant chronic diseases. Age groups were created with even distribution of the sample across groupings. Body-mass index (BMI) was categorised into underweight, normal, and pre-obese/obese based on the World Health Organization classification.18 Data on education, pregnancy, and having children under five were requested but were either not collected or were of insufficient quality and thus not included in this study.

Analytic Strategy

The analytic approach was exploratory. First, the sample distribution across countries and demographic explanatory variables were described. Thereafter, the proportion of residents expressing services gaps were contrasted across the 13 services and countries, then compared across demographics. R version 4.2.1 was used for data cleaning, and Stata/SE 17 for data analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the sample and the service gaps across demographics and specific services.

Poisson regression models with logarithmic-linked functions were used to estimate the relative risk (RR) of residents expressing service gaps by demographic explanatory variables.19 Poisson regression and logarithmic-linked functions were appropriate for this analysis as we present non-negative data and expect to identify multiplicative effects of the explanatory variables on needs expressed by participants. This model was also chosen as RRs are easier for readers to interpret as compared to odds ratios produced in logistic regressions, and this renders greater useability and applicability of the results by organisations. When Poisson regression was applied to data across all localities, variance was adjusted for potential correlation within countries (countries as clusters), whilst when analysing data within a specific country robust error variance was used to improve the reliability of the results.

The explanatory variables of age, gender, household income, BMI, and presence of chronic disease were likely confounders for other variable’s relationship with expressed needs and were accounted for through multiple regression. To explore whether the relationship between household income and expressed needs by residents differed by chronic disease status, an additional multiple regression analysis was conducted with an interaction term between household income and chronic disease. 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p-values were also presented in the analyses.

RESULTS

Within the period of July 2022 to October 2023, 484 153 responses were collected by residents across Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa (Table 1). Majority of respondents were from Indonesia (N=187 802), followed by South Africa (N=113 718), India (N=70 290), Philippines (N=59 657), Kenya (N=49 115), and Cambodia (N=3 661). The distribution of respondents in the sample can be seen in Figure 2. 51·8% of the sample were female, with a median age of 35 (interquartile range [IQR]: 26-46), and median body-mass index (BMI) of 23·6 (IQR: 21·4-26·6). 52·3% of the sample is estimated to be employed, and roughly 6·4% suffer from at least one chronic disease. 36·9% of the sample have a monthly household income of ≤$USD76, 23·7% between $USD77-128, 18·9% between $USD 129-220, and 20·5% >$USD220. Data on employment was only available for 10·9% (N=52 581) of the sample, and none from the South African respondents – therefore because there is a high risk that the mechanism of missing data is missing not at random, instead of imputing missing data, this variable was excluded from subsequent analyses to avoid presenting biased findings.

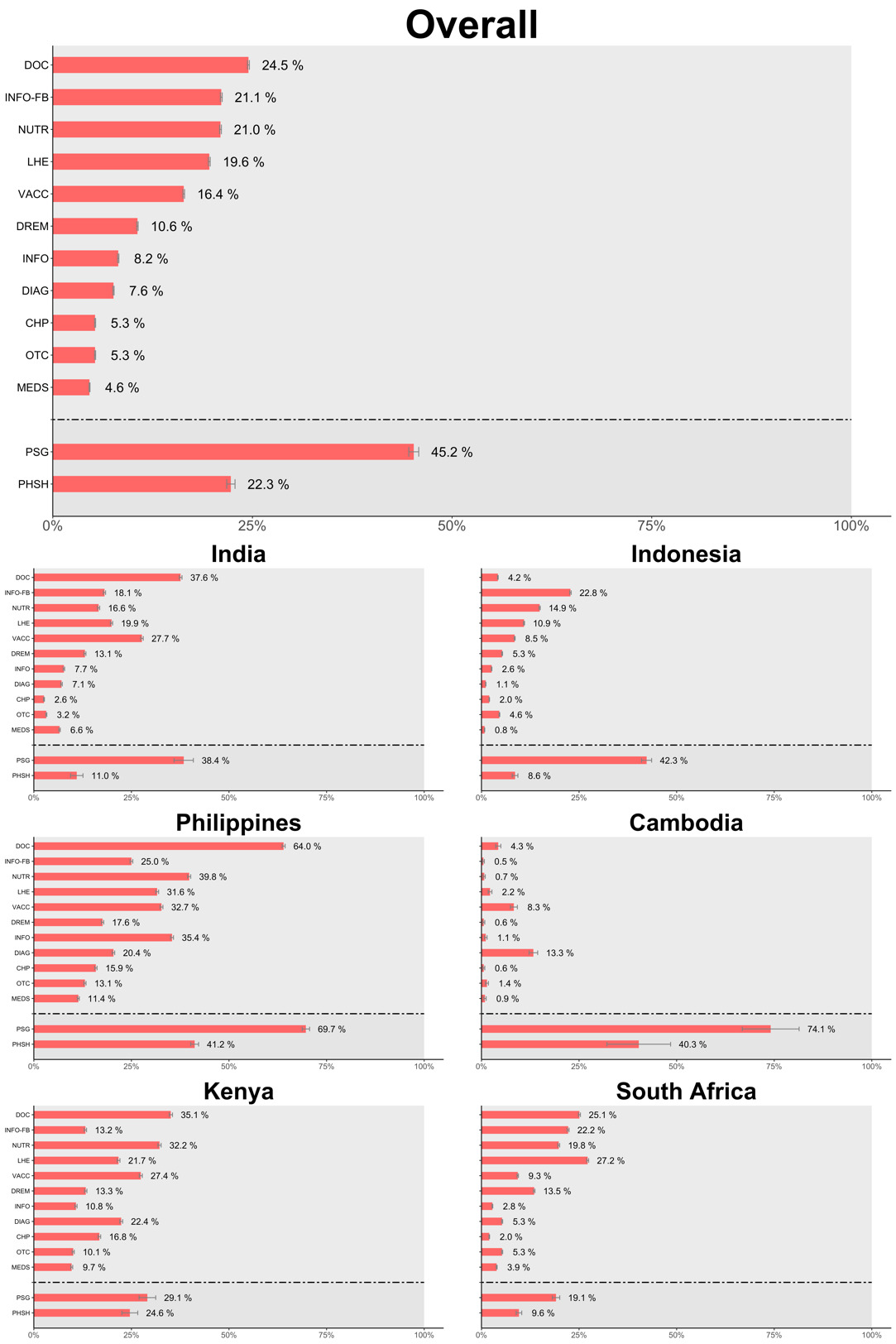

Broken down by the different types of services, overall rural residents found physician services to be of the greatest need (24·5%) – and this is generally consistent across all countries except Indonesia and Cambodia (Figure 3). This is followed by ‘health information through Facebook or WhatsApp’ (21·1%), ‘nutrition or wellness products’ (21·0%), and ‘local health events’ (19·6%). Amongst rural residents with chronic diseases, overall, 45·2% expressed needs for ‘connecting with other patients with the same condition as me[them]’ – this proportion is significantly greater in Philippines and Cambodia with around 70% who expressed need for such a service. Overall, 22·3% of rural residents with chronic diseases expressed need for ‘home personal health services’ – and again this is higher at around 40% in Philippines and Cambodia.

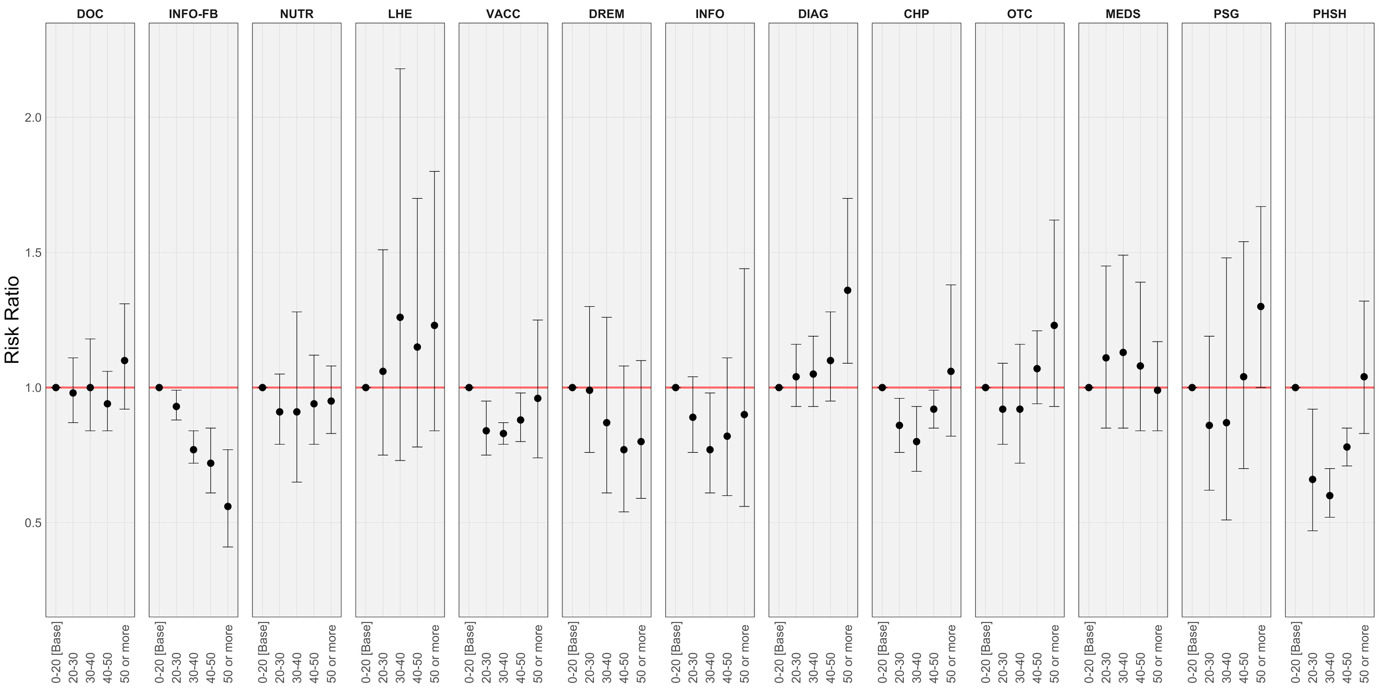

Table 2 (supplementary file 3) compares the expression of needs by rural residents within demographic groups – this results section will highlight only the pertinent findings, and some of these findings are summarised in Figures 4-6. As there was concern for overdispersion of data when looking at outcomes of ‘home personal health services’ and ‘connecting with other patients with the same condition as me’ – analysis of these two services were excluded. Between female and male rural residents there were no critical differences in needs. Between age groups, there is a decreasing trend in expressed needs for ‘health information through Facebook or WhatsApp’ with increasing age – with rural residents above 50 having a 44% (RR=0·56 [95% CI=0·41-0·77], p<0·0001) lower risk of expressing this need compared to those 0 to 20 years (Figure 4). Also, expressed needs for ‘vaccines’ and 'consumer health products; were highest for the youngest age group of 0 to 20 years and oldest age group of 50 or more years, compared to residents aged 20 to 50 years.

With increasing household income there is a decreasing trend in residents expressing needs for ‘health articles I[residents] can read myself[themselves]’, ‘consumer health products’, ‘consumer non-prescription medication’, and ‘affordable medicines’ (Figure 5). Most notably, residents with a household income $USD 129-220 had a 50% (RR=0·50 [95% CI=0·38-0·65], p<0·0001) lower risk of expressing needs for ‘consumer health products’ compared to the lowest income group of ≤$USD76. Lastly, compared to the lowest income group of ≤$USD76, rural residents in the highest income group with >$USD220 generally had a 54% (RR=0·46 [95% CI=0·33-0·65], p<0·0001) lower risk of expressing needs for ‘diagnostic services’.

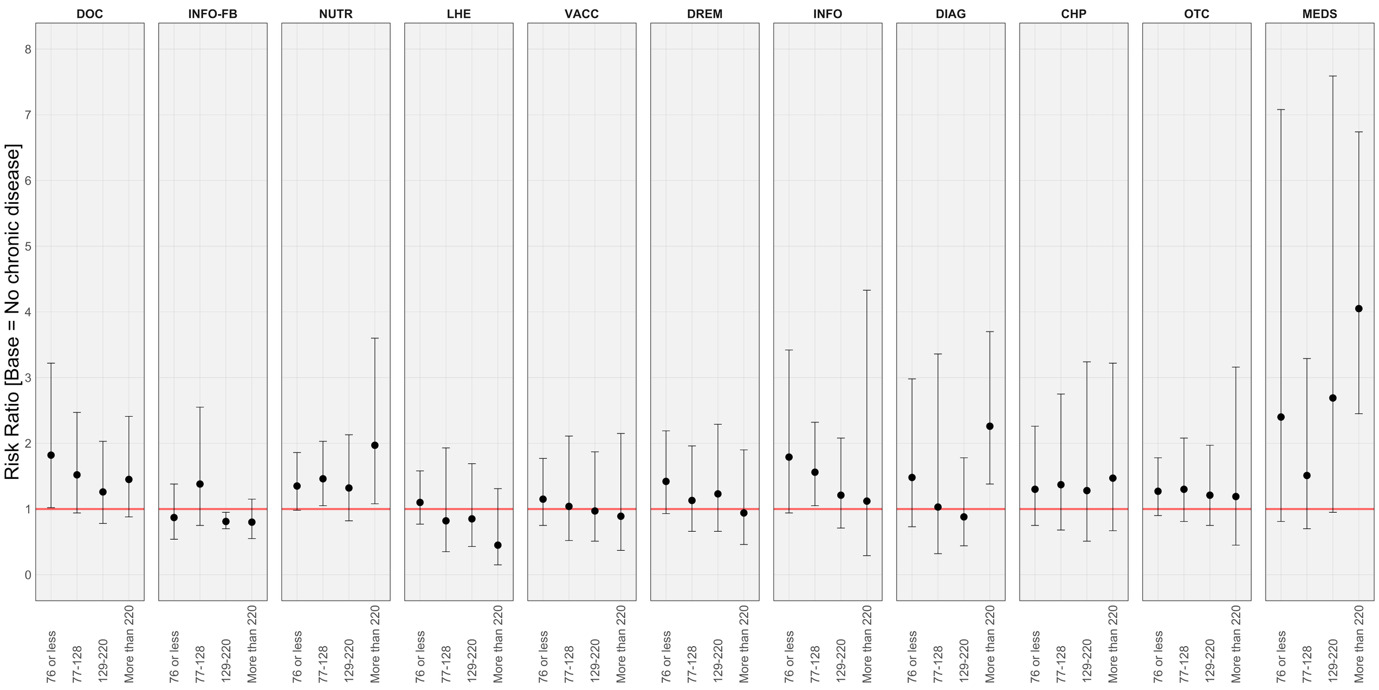

Amongst different BMI categories, residents with a normal BMI had a 29% (RR=0·71 [95% CI=0·61-0·81], p<0·0001) and 21% lower (RR=0·79 [95% CI=0·62-0·99], p<0·05) risk of expressing needs for ‘health articles I[residents] can read myself[themselves]’ and ‘consumer health products’ respectively compared to those who were underweight. Lastly, compared to rural residents with no chronic diseases, residents with chronic diseases had a higher risk of expressing needs for ‘health articles I[residents] read myself[themselves]’ (RR=1·64 [95% CI=1·10-2·43], p<0·05), ‘physician services’ (RR=1·61 [95% CI=1·04-2·48], p<0·05), and ‘nutrition or wellness products’ (RR=1·45 [95% CI=1·02-2·05], p<0·05).

Results of the additional regression analysis including an interaction term between household income and chronic disease are presented in Table 3 (supplementary file 4) and Figure 6 below. The relationship between chronic disease and expressed needs for ‘nutrition or wellness products’ varies significantly by household income (p=0·001), with a trend of higher risk ratios with increasing household income. In the case of ‘diagnostic / screening services’ and ‘affordable medicines’, although in the regression analysis without the interaction term there was no clear relationship between chronic disease and expressed needs for these services, a relationship is seen in residents in the higher household income bracket (>$USD220). Residents in the highest household income bracket with chronic diseases express 2.3 times (95% CI=1.38-3.70) and 4 times (95% CI=2.45-6.74) higher need for ‘diagnostic / screening services’ and ‘affordable medicines’ compared to residents without chronic diseases. The remaining services show no discernable pattern from the additional regression analysis and/or have insignificant interaction terms.

DISCUSSION

With regards to individual-level healthcare services: physician services, nutrition or wellness products and vaccines were highly sought after by rural residents to meet individual health needs. These findings were largely consistent across all the countries studied except for Indonesia where the need for physician services is relatively lower compared to the expressed needs for other services. There are several reasons that can explain this phenomenon: (A) Indonesia has high uptake of its national health insurance20 – therefore the lower expressed need for physician services could be reflective of the reduced financial barriers to access; (B) Indonesia has an extensive network of community and subcommunity health centres (puskesmas), therefore lowering the expressed need for physician services due to easier availability and accessibility of healthcare21; and (C) the low perceived need for physician services could be cultural or related to community usage of traditional healers and traditional medicine.21 In Cambodia, expressed needs for majority of services are relatively lower compared to other countries, which may be explained by cultural norms in perceiving and expressing needs.

Expressed needs for services also differ across patient demographics – such information is helpful for commissioners of services to identify the appropriate target subpopulation for service provision. For example, physician services & nutrition or wellness product are higher in those with chronic diseases, whilst vaccination services and consumer health products are highly sought after in the youngest and oldest age groups. Needs for other medical services such as prescribed medications, over-the-counter prescriptions, and diagnostics vary from country to country and are likely influenced by national or subnational contextual differences – such as the availability and coverage of government subsidies and national health insurances.

Studying the relationships between household income and expressing need for the various services, participants with higher household income generally express lower needs for physical health information and individual healthcare services such as diagnostics, medications (over-the-counter and prescription medicines), and consumer health products. This is likely because higher income households have fewer financial barriers to purchasing these items either by themselves or through a physician’s instruction (such as diagnostic tests and prescription medications). These findings suggest the importance of finding low-cost strategies to provide diagnostics, medicines, and consumer health products to low-income rural households as they have greater needs for such services – likely as it poses a greater opportunity cost.13

This study showed residents have strong interests in health education – especially information acquired from local health-promoting events. Other health needs assessments in Asia have identified strong interests amongst rural residents in planning educational programmes and events in communities – however further research to study the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of specific programmes are to be done – especially since such programmes can consume a high quantity of resources which could be allocated to other cost-effective interventions.6,7 Results from holistic HNAs also form the basis for determining the topics or content that should be covered in health education material. For example, in the study by Kingery et al.,9 participatory methods were used in rural communities in Kenya to identify health needs for residents with the objective of producing health education material. In addition to the identification of health needs, the study also employed participatory methods to prioritise health needs which act to inform planners of the design of health promotion activities. Future studies that aim to design health education material should employ similar approaches as this study, whilst also studying the preferred modalities for delivery of health education material (e.g. physical versus digital material).

In our study, we found a strong interest in acquiring information via social media (i.e Facebook and WhatsApp), especially popular among the younger age groups. This suggests potential for growth of digital health-promoting services in rural communities to empower the younger generation to improve their health and learn to care for the older age groups who may have less digital literacy.22 The popularity of such a service can be attributed to increasing digital connectivity using mobile phones which are increasingly common in rural settings and are becoming integral to daily life. With greater integration of these digital tools into rural communities, utilising digital means would be a natural evolution for rural health messaging.23 However, the cost-effectiveness of such initiatives must be assessed before they are rolled-out at large-scale.22 Additionally, programmes utilising social media to spread health information must mitigate against misinformation and reduce ambiguity and uncertainty of information shared.24,25 Reach52 trains CHWs to spot and counter digital misinformation in their communities and encourage accurate health messaging to residents – this could be a viable solution for other organisations and communities to explore.

Other challenges faced with expanding digital health-promoting services is the lack of integrated databases to facilitate personalised health messaging.25 Considering the strong interest and need for information through ‘health articles’ – especially amongst residents with chronic diseases, low BMI, and in lower income households – there is potential to bridge the gap in this need by leveraging digital health to identify and transmit personalised information, especially in rural areas where the physical delivery of health information can be challenging or inequitable. However, issues of inequity in digital infrastructure (e.g. internet access, reliable electricity provision) must first be addressed, and this can be done with the support of public-private partnerships.25

An important reflection on the conduct of this study is the training and utilisation of CHWs for data collection. CHWs often emerge from specific national socio-cultural contexts in response to a national need and a natural evolution of existing primary care programmes.26 CHWs are embedded within and understand the communities in which they work with and have the potential to make important contributions to improving the health of populations and strengthening health systems.26 A previous project by our team found that CHWs enabled task-shifting – redistributing tasks from trained healthcare workers to CHWs with fewer qualifications.27 This means that CHWs are an efficient and sustainable workforce with the potential to scale-up quickly. A competent CHW can augment health services by saving time and costs on enrolment, data collection, and simple interventions. In the context of this study, CHWs can be mobilised by organisations and local health units to facilitate HNAs, and ensure assessments done at the grassroots make sense to the communities they serve. When considering the broader health system and its objectives, CHWs can be used to bridge the gap between healthcare workers and wider rural communities by being stationed in remote or hard-to-reach areas as is done in some countries.21,26 CHWs can also achieve greater involvement in the community beyond a conventional healthcare worker, by doing health promotion, disease prevention, and facilitating access to healthcare services.26,28 Various countries employ different financial models to make the role of a CHW attractive, such as through direct salary payments or profiting off the sale of essential medicines and health products (e.g. contraceptives, vaccinations), and local governments could explore successful models in other countries for ideas on setting-up a CHW workforce.

The findings of this study offer a preliminary understanding of the needs of rural residents in Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. This list of priorities provides a focus for research, policy development, and programme implementation.10 A potential critique by readers is that this study paints a caricature of a rural resident and seems to ignore an individual’s diversity of needs. In response to this, the authors affirm that this study does not intend to present a comprehensive picture, but merely a preliminary understanding of the universal rural resident to encourage organisations to integrate the findings into their strategies and business plans.6,29 To mitigate against generalisation, data broken down by countries are provided in supplementary file 3. However, diverse landscapes and cultures of rural communities mean national results cannot be generalised to a whole country.9 Therefore, detailed, location-specific HNAs should be conducted that adopt a more needs-based, person-centered, and participatory approach to assessments that combine qualitative and quantitative methods and incorporate multiple perspectives at the municipal, health services, practice, and patient level.5,8,30–32 Organisations should build on this study’s understanding of rural community needs and maintain granularity of information on subpopulations for segment-specific interventions.

Limitations

Our study has a few limitations. Firstly, our service-focused approach of HNA assumes the curated list of options presented to residents are finite and does not explore other community-specific needs.16,33 Although this list of 13 services was built in consultation with local stakeholders, it is unlikely that the list would provide a holistic, collective understanding of rural resident needs. As a result, this study is likely to underreport the totality of health needs and the proportion of rural residents with unmet needs. Whilst the study covered important questions on access to healthcare, preventive, and health education services, it did not incorporate environmental needs and social determinants such as household income, education, water, and employment, which have a strong impact on rural health.9,10 A future study of this nature should build a more comprehensive questionnaire that represents a spectrum of health needs and consider integrating open-ended questions for residents to express needs that fall outside the predetermined list. HNAs should also be repeated at regular intervals to track changes longitudinally.10

Secondly, there were challenges faced in collecting data in rural settings; CHWs shared that rural residents found it difficult to report monthly household income as they do not receive regular monthly salaries. Educational attainment is a potential confounding variable for the relationship between both household income and BMI (especially the malnourished) with felt needs, but could not be included in the regression model due to limitations in data availability.34 Employment is also known to have an impact on health, especially mental health.35 Additionally, employment can also confer residents benefits in terms of health-related claims or insurance which can offset costs for health services, or workplace-based benefits (e.g. occupational doctor) that provide easy access to services. However, again due to the limitations in data availability, employment could not be included in the regression model although it is expected to contribute to our understanding of needs expressed by residents. A future study of this nature should make a concerted effort to collect data on education and employment to be factored into the regression analysis to build our understanding on the unmet needs experienced by different demographics in rural populations.

Thirdly, this HNA did not take a representative sample of the rural population in Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, and did not include other rural communities within the Global South (e.g. Latin America). Sampling was limited to communities in which the team had access to and local partnerships with. The implication is that the results may not be generalisable to all rural communities within Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa and the findings are possibly biased as the data comes from communities that could be easily reached by external organisations as opposed to others that may be highly inaccessible (e.g. rural communities in highlands, mountainous regions, or small islands). Future work could explore taking more representative samples from rural communities across the Global South – and this can only be done through multi-centre collaborations. Such a task is outside the scope of this project and will require significant large-scale investment of time and resources but could be invaluable to advancing our knowledge of rural health.

Lastly, in this study we measured felt needs. Although felt needs or resident perceptions of unmet needs can have strong predictive capabilities for mortality in certain populations, it conflates needs with wants.16,34,36,37 Problems arise when wants inflate needs for personal desire, or decrease needs due to a resident’s poor consciousness of what is satisfactory health.34 Despite this limitation, our study accepted the assumption that providers and organisations keen to enter the rural health system have little knowledge of consumer needs, and therefore a liberal understanding of needs from the perspective of rural consumers would be a good starting point. The implication of this approach is that providers and organisations can use the findings of this study as a starting point but must conduct their own HNAs for specific communities to paint an accurate contextual understanding of the specific rural communities’ needs.

CONCLUSIONS

Rural communities in the Global South should receive greater attention to both individual service needs for physicians, nutrition and wellness products, and vaccines, as well as health promotion needs through local health events and social media. CHWs were identified as an efficient and sustainable workforce that could play the role of cultural ambassador. This study provides a universal profile to organisations and suppliers to begin scoping their work to address unmet needs in rural communities. However, any strategy must be supplemented by locally contextualised HNAs that are needs-based, person-centered, participatory, and make a concerted effort to reach the poor and disadvantaged.8,13,30,31 Organisations focusing on service-delivery should integrate longitudinal HNAs into their daily processes, and widely publish and share their findings to continue to attract other parties to work towards better health and access to care in rural communities in the Global South.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all the residents, community leaders, CHWs, local and governmental partners in the respective districts and countries who contributed to this HNA. Special thanks to the hardworking team at reach52 which worked behind the scenes to coordinate with local partners, support data collection, ensure safe data management, and maintain the digital platform.

Ethics statement

The data analysed in this study was gathered through daily ground operations and collection of basic demographic information, in accordance with stringent procedures established by reach52 for all participants. Rigorous measures were undertaken to ensure adherence to the highest ethical standards. Prior to data collection, explicit informed consent was obtained from each participant and stringent protocols were implemented to safeguard the privacy and confidentiality of all data collected. Refer to the methodology section, under “Data Protection” for more information.

Funding

This research did not receive any direct grant from external funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. Minimal funds were allotted by reach52 to employ a part-time researcher to develop the project, analyse the data, and generate the manuscript.

Authorship contributions

M.T.W, L.A, J.P, and L.J.L conceived of the manuscript idea. M.T.W developed the methodology and performed the data analysis with the help of L.A and J.P. M.T.W, L.A and J.P developed the initial draft, X.L checked through to make sure the project was sound. All authors thereafter contributed to the writing of the final manuscript.

Disclosure of interest

All authors are affiliated with reach52 – a social enterprise that seeks to achieve sustainable social impact. The organisation derives revenue to sustain its model of care from the sale of rural health-focused campaigns to commercial partners or from research/campaign grants.

Additional material

Online supplementary document contains supplementary files 1-5 for reference.

Correspondence to:

Muhammad Taufeeq Wahab

National University Health System

1E Kent Ridge Road, Singapore 119228

Singapore

muhammad.taufeeq@mohh.com.sg

_and_specific_service_gaps.tiff)

_and_specific_service_gaps.tiff)