INTRODUCTION

Abdominal obesity (AO), a stronger predictor of cardiometabolic risk than general obesity measured by body mass index (BMI), has been increasing rapidly over the past decade1,2 AO, characterized by increased abdominal fat, negatively impacts health by reducing life expectancy and contributing to chronic diseases like diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease.3,4 Globally, 41.5% of adults have AO, and its prevalence is rising in both developed and developing countries, including sub-Saharan Africa (SSA).2,5 In SSA, the World Health Organization (WHO) defines AO as a waist circumference (WC) ≥94 cm for men and ≥80 cm for women, with prevalence rates ranging from 33.8% to 77.7%.6,7

In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), increasing urbanization and socio-economic changes contribute to AO. Studies report a prevalence of 13.5% in 2014 and 45.5% in 2022.4,8 BMI, widely used for weight monitoring, is limited as it does not account for fat distribution.9 AO is typically measured using WC, waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), or waist-to-height ratio (WHtR), but each method has limitations. For example, WHR can be misleading after weight loss, and WC requires ethnicity-specific values, leading to potential inaccuracies.10,11

WHtR is gaining attention as a better predictor of cardiometabolic risk due to its simplicity and universal applicability. A WHtR threshold of 0.5 is suggested for both children and adults, regardless of ethnicity or gender, promoting the guideline to “keep your waist circumference less than half your height”.12,13 Studies in Africa, such as those in Nigeria (2016) and South Africa (2020), support the relevance of WHtR in assessing AO.14,15

In the DRC, most studies on AO have relied on WC rather than WHtR. This study aims to evaluate the concordance between these two measures of abdominal obesity among Congolese adults in the Gombe Matadi Health Zone.

METHODS

Study framework

The survey was conducted in the rural Health Zone of Gombe-Matadi, encompassing 15 health areas (HAs) with a population of 21,659 as of May 2019. It focused on three HAs: Gombe-Matadi (26 villages, commercial hub), Yanda (26 villages, religious area influenced by Nkamba city, headquarters of the Kimbanguist Church), and Ntimansi (25 villages, strictly rural).

This study represents a secondary analysis of data collected during a cross-sectional survey investigating the prevalence of diabetes and its risk factors among adults in the Gombe-Matadi Health Zone.16

Study type

The analysis was based on the primary data gathered for the aforementioned cross-sectional study.

Study population

The target population included adults aged 19 years or older of both sexes. Pregnant women, individuals with severe psychiatric disorders, and non-Congolese residents were excluded. Inclusion criteria required complete data for analysis

Sampling technique

The statistical unit was an adult, with a primary study sample size of 1,531 individuals. Sampling was conducted in five stages:

The sampling process began with the random selection of three health areas (HAs) as clusters for the study. Within these clusters, villages were chosen based on specific criteria, including a demographic weight exceeding 200 inhabitants and a proximity of less than 4 kilometers from the study site. Next, systematic sampling was conducted to select inhabited plots within each village. From these identified plots, households were randomly chosen through simple random sampling, ensuring unbiased representation. Finally, eligible individuals within each selected household were randomly chosen to participate in the study, creating a robust and comprehensive sampling framework.

Data collection

A questionnaire was designed to extract data from the primary dataset. Sociodemographic characteristics (sex, age, education level, occupation) and anthropometric measurements (weight, height, waist circumference) were analyzed. General obesity was classified using BMI (≥30 kg/m²) (26), while abdominal obesity was defined by WC thresholds (≥94 cm for men, ≥80 cm for women) (27) and WHtR (≥0.5).13

Measurement procedures

Anthropometric measurements were performed using standardized techniques to ensure accuracy and consistency. Weight was measured using a SECA® electronic scale with a precision of 0.1 kg. Height was assessed with a SECA portable stadiometer, with each child standing upright and barefoot to ensure correct posture. Waist circumference was measured using a non-elastic measuring tape, placed midway between the lower rib margin and the iliac crest, with an accuracy of 0.1 cm.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS27, while graphs were generated using Excel 2016. Qualitative variables were summarized as percentages. The Kappa coefficient was calculated to assess agreement between WHtR and WC for diagnosing abdominal obesity. Subgroup analyses stratified by sex and demographic factors were performed, and Kappa values were interpreted following the Landis and Koch classification.17

Ethics statement

The original study was approved by the National Committee for Ethics in the DRC (104/CNES/BN/PMMF/2018 of 23/01/2019). Written informed consent was obtained from participants, and data were handled confidentially. Patients received appropriate treatment and were referred for follow-up care. The methods adhered to all relevant ethical guidelines and regulations.

RESULTS

Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants

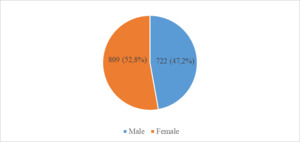

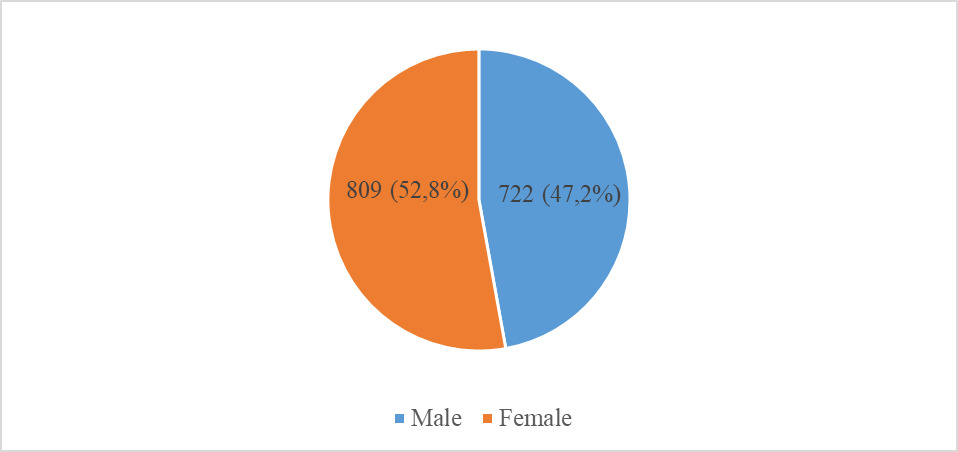

Women were more numerous (52.8%), resulting in a sex ratio of 0.9.

Characteristics of Participants by Age Group, Level of Study, and Profession

The demographic breakdown of participants is analyzed based on their age group, education level, and professional engagement. These characteristics are summarized and presented in Table 1.

Among the 1531 participants, the population is predominantly middle-aged, with the 51-60 and 61-70 age groups each accounting for approximately 2 out of 10 individuals. The average age was 49.7 ± 14.7 years. Nearly 7 out of 10 participants had completed secondary education, and employment was highly prevalent, with more than 9 out of 10 participants engaged in work.

Obesity among participants

General obesity

The nutritional status of participants, categorised based on their Body Mass Index (BMI), is presented in Table 2.

Among the 1,531 participants, 3.7% were classified as generally obese, with women showing higher prevalence than men.

Abdominal obesity assessed by waist circumference (WC)

The abdominal obesity among participants, based on waist circumference measurements, is summarized in Table 3.

Less than half the participants among the sample (32.1%) had abdominal obesity at WC. Less than a quarter of all men of the sample had abdominal obesity and Almost half of women were obese by WC.

Abdominal Obesity Assessed by Waist-to-Height Ratio (WHtR)

The prevalence and distribution of abdominal obesity among participants, evaluated using the Waist-to-Height Ratio (WHtR), are detailed in Table 4.

At the standardized WHtR threshold of 0.5, the findings revealed a significant prevalence of abdominal obesity, affecting 70.6% of participants. This high rate highlights that nearly three-quarters of the study population were classified as having abdominal obesity, with a higher proportion observed among women compared to men

The agreement between WHtR and WC in diagnosing abdominal obesity among participants is analyzed and presented in Table 5.

The results show a high prevalence of abdominal obesity, with 70.6% of participants classified as obese based on the WHtR threshold. Notably, 32.0% of participants were identified as obese by both WC and WHtR measures, demonstrating substantial agreement between the two methods. However, WHtR appears to be more sensitive, capturing a larger proportion (38.6%) of cases that WC does not identify (Table 6).

The Kappa coefficient of 0.32 reflects weak agreement between the waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) and waist circumference (WC), with an overall agreement of 61.3% for diagnosing abdominal obesity. The expected agreement by chance is 42.64%, and the small standard error of 0.0308 ensures a precise estimate. The high Z-score (17.13) and significant p-value confirm the statistical reliability of the findings.

Concordance between the diagnosis of abdominal obesity by waist-to-waist ratio and waist circumference by gender is presented in Table 7.

The concordance analysis reveals a moderate agreement (Kappa = 0.4271) for males and a weak agreement (Kappa = 0.2235) for females between WHtR and WC in diagnosing abdominal obesity. The statistically significant Z-scores and p-values confirm the reliability of these findings despite differences in agreement levels by sex.

DISCUSSION

Findings of the study

Among the 1,531 respondents, 72% were aged 40 years or older, with women predominating the sample, consistent with demographic data from the DRC.18 This could be explained by the higher female population and migration patterns, as individuals pursuing higher education tend to leave rural areas for urban centers, where they often remain for employment. General obesity was low, affecting only 3.7% of participants, a result similar to studies conducted in rural Nigeria19 and South Kivu, DRC.20 This contrasts with higher prevalence rates found in urban DRC, such as 52% in 200721 and 34.6% in 2023.22 The low prevalence in our study may be due to the limitations of BMI as a diagnostic tool, as it fails to account for fat distribution or body composition.23,24

Abdominal obesity

Abdominal obesity was markedly higher, with prevalence rates of 70.6% by waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) and 32.1% by waist circumference (WC). WHtR identified a greater proportion of individuals at risk, reflecting its superior sensitivity and strong association with cardiometabolic risks.25 WHtR is recognized as a simple, valid, and reliable index for detecting abdominal obesity, with a universal threshold of 0.5 applicable across genders and ethnicities.12,26 In contrast, WC requires multiple gender-specific thresholds, limiting its universal applicability.12 The high prevalence of abdominal obesity in this rural area may be influenced by the commercial nature of Gombe Matadi, which facilitates access to unhealthy, calorie-dense foods, as well as by Yanda’s role as a religious hub with international exchanges.

Concordance between WHtR and WC

The agreement between WHtR and WC for diagnosing abdominal obesity was low, with a Kappa coefficient of 0.32, indicating weak concordance. This suggests that the two measures are not interchangeable, as they capture different dimensions of abdominal obesity. The significant discrepancy in prevalence rates between WHtR (70.6%) and WC (32.1%) may explain this low agreement. In contrast, studies with higher concordance typically report similar proportions for the two measures.27,28 These findings emphasize the need to consider the strengths and limitations of each method when assessing abdominal obesity in diverse populations

Limitations

This study is among the few in the DRC, and possibly the first, to compare waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) and waist circumference (WC) in assessing abdominal obesity. It stands out for being conducted in a rural setting, emphasizing the value of WHtR as a predictive tool for cardiometabolic risk. Additionally, the study’s large sample size adds robustness to its findings, especially given the challenges of conducting research in the current economic context.

The absence of a reference test to establish a definitive diagnosis of obesity is a notable limitation. Furthermore, the study relied on three diagnostic methods—BMI, WC, and WHtR—while omitting more precise techniques such as bioelectrical impedance analysis, which is widely regarded as an effective method for assessing body composition. These constraints may have affected the comprehensiveness of the findings.

Conclusions

Measuring abdominal obesity solely with waist circumference often underestimates its prevalence. This study underscores the need to integrate both waist circumference (WC) and waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) for a more accurate assessment, enabling better decision-making to promote public health in the DRC. The dual approach is recommended for clinical and research purposes, as it improves detection of at-risk individuals. Politically, these findings are significant given the rising risk of cardiovascular diseases (diabetes, hypertension, heart disease) and the challenges in healthcare management, particularly in rural areas where limited access to specialists hinders effective treatment.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the project “Renforcement Institutionnel pour les Politiques de Santé basées sur l’Évidence au Congo (RIPSEC),” funded by the European Union, within whose framework this study was conducted. While the project provided financial support, it had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation of results, manuscript preparation, or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Authorship contributions

The study design was conceptualized and developed by Nzau Mavinga Palmich, Bernard-Kennedy Nkongolo, Steve Botomba, and Muel Telo Marie-Claire Muyer. Data collection was conducted by Nzau Mavinga Palmich. The manuscript was written collaboratively by Nzau Mavinga Palmich, Bernard-Kennedy Nkongolo, Steve Botomba, and Muel Telo Marie-Claire Muyer. The final version of the article was critically revised and approved by all four authors..

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.