Introduction

Hearing loss is a growing global health concern, with the World Health Organization estimating that by 2050, approximately 2.5 billion people worldwide will experience some degree of hearing impairment.1 Of these, over 700 million individuals—roughly one in ten—will suffer from disabling hearing loss, defined as a hearing threshold greater than 35 dB HL in the better ear.2 Beyond its impact on communication, hearing loss has significant and often unseen consequences on cognitive and overall health. Studies suggest a strong correlation between hearing impairment and dementia,3–5 as well as an increased overall mortality rate.6 Despite these serious implications, access to hearing healthcare remains inequitable, particularly in low- and middle-income countries where early intervention programs are scarce.

In pediatric populations, pre-lingual hearing loss critically affects speech and language development. Recognizing the importance of early detection, the Joint Committee of Infant Hearing (JCIH) has established a recommended timeline for screening and intervention: hearing assessment by one month of age, diagnosis by two months, and intervention by three months.7 While post-lingual hearing loss in adults may not seem as urgent, its impact on quality of life is profound. Individuals with significant hearing loss often experience depression8 and social isolation,9 both of which are independent risk factors for dementia.10 In fact, hearing loss is recognized as the largest modifiable risk factor for dementia, contributing to nearly 9% of cases worldwide.10

The Philippines has a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of USD $471.5 billion and estimated GDP per capita of USD $4130.11 The country of approximately 114 million people across seventeen regions, faces unique challenges in addressing non-communicable diseases (NCDs) like hearing impairment.12 While communicable diseases such as malaria and cholera continue to strain healthcare resources, NCDs have emerged as the leading cause of disease burden. In 2019, they accounted for 70% of the nation’s 600,000 deaths, and their impact is projected to rise.13 While infectious diseases (such as tuberculosis and lower respiratory tract infections) and maternal and child health conditions still contribute significantly to the overall disease burden, their share has declined over the past three decades.14 The economic cost of NCDs is substantial, amounting to 22.6 billion USD dollars—equivalent to 4.8% of the country’s GDP.15 Despite these figures, hearing loss has not received the same level of prioritization as other NCDs, leaving significant gaps in screening and intervention services.

Tacloban City, the provincial capital of Leyte in Eastern Visayas, serves a population of approximately 251,881 individuals.16 Yet, there is no formal adult hearing screening program in place, reflecting broader systemic challenges in healthcare delivery. Limited funding, competing health priorities, and a lack of public awareness contribute to this gap. Recognizing this need, our study team collaborated with the Philippine Department of Health and the non-profit EyeHear Foundation to implement a hearing screening initiative in September 2023. The program identified individuals at risk, provided counseling on appropriate follow-up interventions, and donated audiometric equipment to ensure the sustainability of local screening efforts.

By addressing hearing loss as a public health priority and integrating it into existing NCD strategies, countries like the Philippines can take meaningful steps toward reducing its long-term impact. Our initiative in Tacloban City serves as a model for expanding hearing healthcare access in communities with less accessibility to hearing healthcare and highlights the urgent need for national-level policy support. Tacloban, the regional center of Eastern Visayas, offers a range of healthcare services through both public and private institutions. Public hospitals include the Eastern Visayas Medical Center (EVMC) and Tacloban City Hospital. Private facilities encompass ACE Medical Center Tacloban, Divine Word Hospital, Our Mother of Mercy Hospital, Remedios Trinidad Romualdez Hospital, and Tacloban Doctors Medical Center. Despite this health infrastructure, Tacloban faces challenges in healthcare delivery, particularly in the aftermath of natural disasters. The devastation caused by Typhoon Haiyan in 2013 severely impacted the city’s healthcare system, highlighting vulnerabilities in medical infrastructure and the need for external aid. Accessibility to hearing health in rural areas is limited and focus on health delivery is on communicable diseases.

Methods

This is an observational, cross-sectional study undertaken at two quiet rooms within the compound of the Department of Health in Tacloban City in region 8, Tacloban between 11-15th September 2023. The study was funded by the Singhealth Duke-NUS global health institute (SDGHI) and an ethics board exemption was granted. We discussed partnership details with EyeHear foundation, who linked the study team members up with the Department of Health and Eastern Visayas Regional Medical Center (EVRMC). A detailed screening protocol was established, and staff members identified were trained over a week on conducting video-otoscopy, tympanometry, and audiometry screening. Staff members were mainly certified nurses, nursing assistants and administrative executives of both EyeHear foundation and Department of Health Region 8.

Procedures

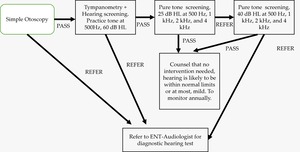

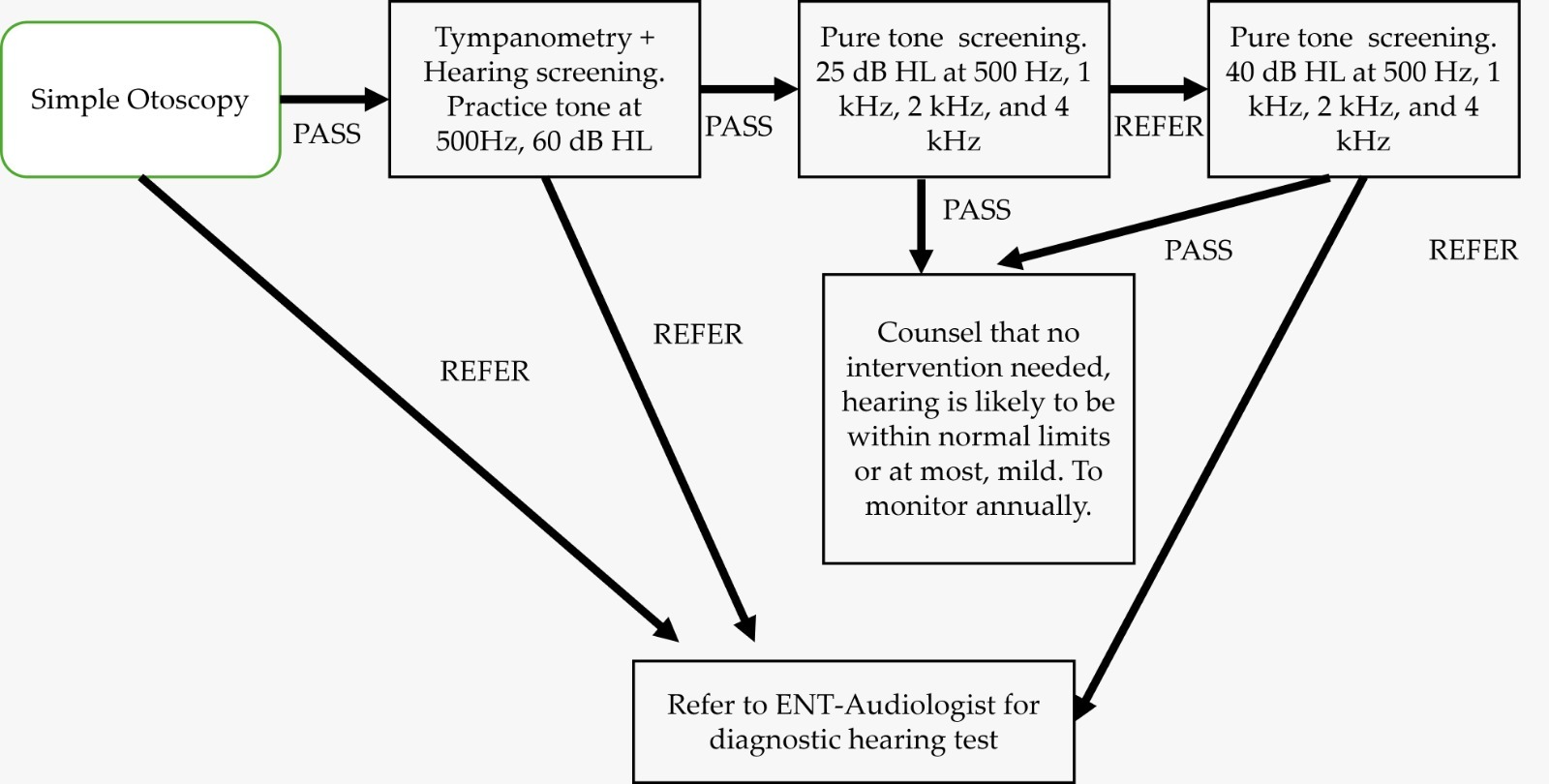

Participants were recruited from a region wide call by the Department of Health and EyeHear foundation. They first underwent a simple intake interview where they were asked about whether they experienced tinnitus and/ or ear discharge as well as whether they were currently working. The Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly-Screening (HHIE-S) was then administered for those who were not working. Following this, participants then undertook video-otoscopy and when results were abnormal, they were referred to the regional medical center for further medical attention. Tympanometry was carried out for those who passed otoscopy examination to assess the middle ear before audiometric screening. We utilized a two-step screening protocol to assess 4 frequencies at 25dbHL and 40dbHL. Details of the screening protocol can be found in Figure 1.

Hearing Conservation Education

The principles of hearing protection such as walking away from loud noise sources, turning down the volume when possible and protecting ears with hearing protection were taught to all participants as part of public health hearing education. Such key messages have been well identified in a global hearing conservation program, namely Dangerous Decibels and were selected for their simple yet effective message. Participants were also taught not to pick their ears and to keep ears dry whenever possible to prevent ear infections. They were educated on the self-cleansing properties of the ears and advised against use of external instrumentation to remove ear wax.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was done using IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) v16.0. The Shapiro-Wilk test of normality was done for all continuous variables. Median and interquartile range were used to summarize data which was not normally distributed (p<0.05). Pearson’s chi-square test was used for categorical data and the Mann-Whitney U test was used for continuous data. Non-parametric Spearman Rho correlation analysis was done to determine the correlation between HHIE-S scores and the Pure Tone Average (PTA) in the Better ear and Poorer ear.

Results

A total of 166 participants were recruited for the study. 6 (3.6%) participants did not turn up and of the 160 participants, the median age was 42 (IQR 35; min-max: 7-89). Demographic details of the participants can be found in Table 1. Of the 160 participants, 16 declined further investigation leaving 144 participants who proceed with video-otoscopy. 15(10.4%) had an abnormal otoscopy, which was either a discharging ear or perforated eardrum, requiring onward referral to an Ear-Nose and Throat (ENT) doctor for further medical attention. 12(8.3%) participants had partial wax occlusion while 6 (4.2%) were referred for severe dizziness, tinnitus or non-otologic concerns (figure 2). We excluded 15 participants from audiometric screening due to abnormal otoscopy. Of the remaining participants, 129 participants (258 ears) had tympanograms analysed and 20(15.5%;40 ears) were abnormal types with a type B or C (Table 2). All 129 participants proceeded with audiometric screening.

More than half the participants failed the audiometric screening protocol at 40dbHL across four frequencies (75/129; 58.1%), leaving 54 participants (41.9%) who likely have not more than a mild degree of hearing impairment and hence did not require urgent follow up. Of the 75 participants who failed the screening, 11(15%) had bilateral severe to profound congenital hearing loss with one participant noting a history of diagnosed cochlear nerve aplasia. 3 (4%) participants had adult onset, post-lingual deafness with severe to profound sensorineural hearing loss in one or both ears. 18 participants (24%) had asymmetrical sensorineural hearing loss type while 19 (25%) accepted further hearing aid evaluation. The remaining 24(32%) declined hearing aid evaluation.

Of the 129 participants screened, 40 participants also completed a hearing handicap inventory questionnaire to assess their self-perceived hearing handicap. The median pure tone average (PTA) of four frequencies (500Hz, 1KHz, 2KHz and 4KHz) in the better ear was 42 dB HL (Interquartile range; IQR: 27 dB) and 57 dB HL in the poorer ear (IQR: 34 dB HL). There was a significant medium positive correlation between PTA (Better ear) and PTA (poorer ear) with hearing handicap scores (p=0.002 and 0.024 <0.05 respectively, table 3). However, a stronger correlation between PTA (better ear) and hearing handicap was established as compared to PTA (poorer ear) (Correlation co-efficient=0.481 (PTA better ear) and 0.356 (PTA poorer ear)). This suggests that most participants depended greatly on their better hearing ear and self-perceived hearing handicap may be underestimated due to compensation of hearing in the better ear. This is supported in the literature when we look at participants with single-sided deafness and asymmetrical hearing loss, where heterogeneity is reported with outcomes from hearing intervention.17 Health policy planners should be aware that low acquisition of hearing aids and adoption of hearing solutions may have less to do with awareness and accessibility to resources but with greater tolerance with better hearing in one ear. Assessing the consequences of hearing loss through mixed-method studies including qualitative analyses are scarce and hence, warranted.

Discussion

Although the demographic age of participants recruited were arguably younger, Tacloban’s (Philippines) life-expectancy is approximately 12 years lower than the average life-expectancy globally. Hence, the health outcomes expected of participants in the 40s may commensurate better with an older adult in the 50s. Almost 16% of participants had abnormal middle ear analyses, which required further middle ear investigations and prompt referrals to ENT doctors. Especially for a type B tympanogram, there could be compromised air reserves in the middle ear, due to chronic otomastioditis, requiring close follow up, or chronic blockage of the eustachian tube by space occupying lesions. A flexible nasoendoscopy is usually used to rule out a posterior nasal space (PNS) mass in the event of a type B tympanogram. Participants may be unaware that they need follow-up surveillance and extensive counselling was required. Close to 20% of those who failed screening also had severe to profound sensorineural hearing loss (figure 3), mostly of a congenital type and late for further intervention, due to long periods of auditory deprivation. However, for 3 participants with post-lingual deafness, cochlear implantation was recommended. It is believed that with fewer years of auditory deprivation and with aural rehabilitation post implantation, success with hearing rehabilitation can be achieved. These participants were referred to our partnered EVRMC, where they may be eligible for financial assistance from the government. A quarter of participants who failed the screening also had incidental asymmetrical sensorineural hearing loss type (figure 3), which normally requires further radiographic imaging to rule out space occupying lesions, vascular conflict and/or pathology of the inner ear. These patients were referred for further medical investigations. Of the participants who required hearing aid evaluation, about half of them (24/43) declined and the rest had satisfactory trial outcomes at hearing aid evaluation. We referred 19 patients after hearing aid evaluation to partnered EVRMC to apply for financial subsidy for hearing aid prescription. These participants will be closely monitored by the EyeHear foundation, who will provide eventual hearing aid fitting and follow up care at their satellite clinics.

While the findings from this study provide critical insights into hearing health in Tacloban, a comparative analysis with similar studies in other regions or countries would strengthen the argument for improved local hearing care policies.

Research from other developing nations with similar healthcare access challenges could highlight common barriers and effective intervention strategies. For example, studies from rural areas in Indonesia18 and Vietnam19 have shown that limited access to follow-up care post-hearing screening significantly impacts long-term hearing outcomes. A comparative evaluation with these studies may help policymakers in the Philippines allocate resources more efficiently.

Moreover, the findings from this study should directly inform health policy and resource allocation in the Philippines. The high prevalence of severe-to-profound sensorineural hearing loss and middle ear abnormalities underscores the need for enhanced funding toward early intervention programs. Policies should prioritize the expansion of screening programs beyond newborn hearing tests to include routine school-age hearing assessments. Additionally, improving financial assistance programs for hearing aid and cochlear implantation candidates will enhance accessibility to treatment.

With all health screening efforts, follow-up care and management are the most important. Challenges encountered in this study include not being able to secure direct financial resources for immediate hearing aid prescription and late intervention for about 20% of participants with severe to profound hearing loss in need of a cochlear implantation. This suggests that despite universal new-born hearing screening in the Philippines, accessibility and affordability for follow-up interventions is still a concern. Nevertheless, we were able to counsel many participants on the need to follow up for their middle ear issues, asymmetrical sensorineural hearing loss or abnormal otoscopy due to ear infections. With partners such as EyeHear foundation and the Department of Health (region 8), participants were able to get promptly referred to EVRMC. Conductive and mixed pathologies of the ear is also beyond the scope of this screening as the study team was not able to conduct bone-conduction testing due to the limitations of noise without a sound-treated booth. Although a type A tympanogram does not rule out a middle ear problem such as an otosclerosis, we could only refer abnormal tympanograms which usually correlates strongly with middle ear problems. We encouraged the director of region 8 to continue hearing screening efforts and hope that a hearing screening program can be established in time given that staff members are now trained on performing basic video-otoscopy, tympanometry, and audiometric screening. One of the limitations of this study include a narrow representation of the population. Recruitment was undertaken by staff from the Department of Health, Region 8 and EyeHear Foundation. This may not be representative of the population at large in Tacloban. Future studies should recruit different segments of the population group for a more general representation. Furthermore, the use of sound-proof booth remains the gold-standard in diagnostic audiometry. Out-of-booth methods in recent years have gained traction in diagnostic equivalency. However, in our protocol we struggled with measuring accurate bone conduction thresholds due to noise. We mitigated noise interference by switching off the air conditioning and conducting the test in a corner room, away from the main road. We also used a calibrated sound level meter to observe the noise floor and interrupted testing whenever noise floor exceeds the criteria. In our opinion, our out of booth method is adequate for screening but because bone conduction thresholds were unobtainable, we do not have diagnostic information.

Conclusions

Greater awareness of hearing health is needed in Tacloban, Philippines region 8 and partnership with stakeholders such as non-profit organisations and the Department of Health is necessary to achieve goals of hearing conservation. Local studies are scarce and without adequate data on the burden of ear diseases, policies for resource and capacity building in hearing health cannot be formulated effectively. More advocacy is needed and with continuation of hearing screening in region 8, we hope that EyeHear foundation will be able to expand their screening efforts to other regions in time. Data should then be collected on the follow up care provided to assess the effectiveness of this hearing screening program as it matures. Future research should aim to collect data on long-term outcomes of hearing interventions, including post-implantation speech and language development, hearing aid retention rates, and patient satisfaction with assistive devices. Additionally, studying the cost-effectiveness of out-of-booth screening methods compared to gold-standard soundproof booth testing would be beneficial. Scaling the screening program should involve training more healthcare workers in audiometric screening and tympanometry, as well as integrating tele-audiology services to extend access to remote communities.

Efforts to sustain and expand hearing screening programs in Tacloban should focus on continuous collaboration with organizations such as the EyeHear Foundation and the Department of Health. Strengthening referral pathways and establishing a government-backed subsidy for hearing care services will ensure better long-term hearing health outcomes for the community.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the Duke-NUS Academic Clinical Programme [Grant number 04/FY2022/P1/22-A37]. The authors would like to thank all staff from the Department of Health Region 8 and the Eyewear Foundation for their administrative support in making this hearing screening program a success. The authors would also like to thank Duke-NUS global health for the grant, and Changi Health Fund for sponsoring this publication. The medical equipment was donated to the Phillippines team as part of our corporate social responsibility.

Conflict of interest

None to declare.

Correspondence to:

Ms. Hazel Yeo, Audiology, Allied Health, Changi General Hospital

hazel_yeo@cgh.com.sg

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)