Introduction

This viewpoint highlights recent developments in Ethiopia in the government’s and its partners’ work to advance a Nexus approach specifically for nutrition. The aim is to contribute to sharing Ethiopia’s learning, particularly with other crisis-prone countries facing similar challenges in tackling persistently high levels of malnutrition.

Endorsed internationally in 2016, the Grand Bargain agreed on the need to strengthen the operational connections between humanitarian, development and peace (HDP) actions to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of humanitarian actions.1 The so-called Nexus approach aims to simultaneously: i) promote early recovery and transitions out of humanitarian needs, ii) build resilience to mitigate future impacts of crisis and iii) prevent future crises by addressing their structural causes.

The need for a Nexus approach is framed around the high volume, cost and increasing length of humanitarian response over the past 10 years. Protracted and complex crises need actors to deliver more sustainable impacts and strengthen and sustain systems through what is often termed, ‘localisation’ of efforts. This is where national and local actors are empowered and financed to drive actions that reduce people’s risks and vulnerabilities to crisis. The Nexus approach typically involves anticipatory actions that are carried out prior to the onset of crisis based on pre-defined early warning indicators. Pre-allocated funds are released to support interventions that build the resilience of populations to withstand existing and future shocks.

Eight years on since the Grand Bargain, recent evaluations2,3 indicate that only limited progress in advancing a Nexus approach in crisis vulnerable countries has been made. It appears that the approach has remained largely conceptual and therefore, there are very few country examples of where progress and impact has been demonstrated. This is particularly true for the nutrition sector where there is even less documented good practice evidence, yet recurrent humanitarian interventions dominate the landscape in protracted crisis contexts and programmes to prevent malnutrition are often poorly funded and implemented.

The situation and challenges in Ethiopia

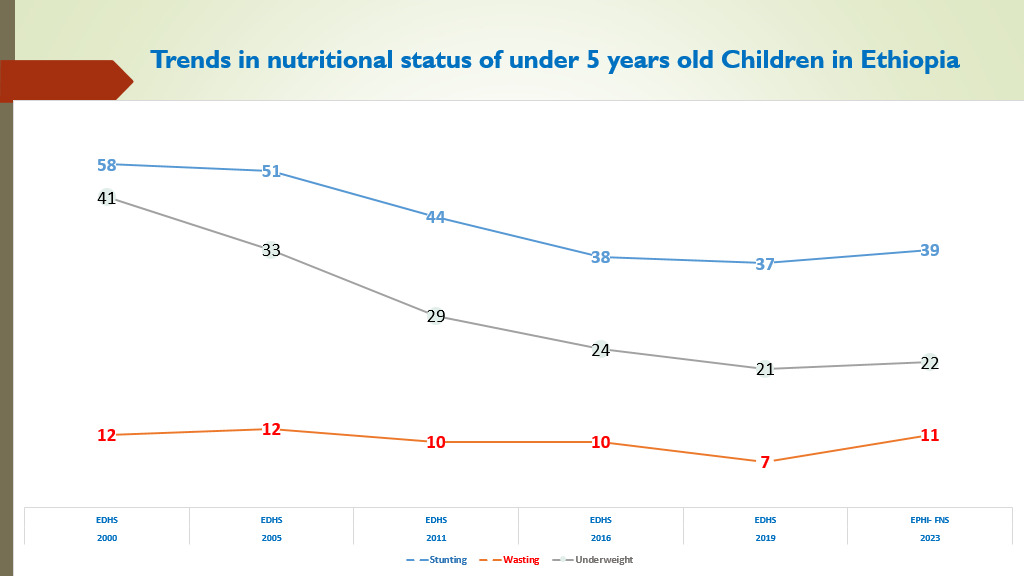

Ethiopia has suffered decades of crisis driven by drought, conflict, climate change, political and economic instability, the COVID-19 pandemic and recent cost of living crisis. These crises give rise to high levels of food, health and nutrition insecurity in the most vulnerable population groups including infants, young children, adolescents and women of childbearing age. Alarmingly, levels of child stunting (low height for age) and wasting (low weight for height) between 2019 and 2023 increased from 37 percent to 39 percent and from 7 percent to 11 percent respectively as shown in figure 1.4 The reasons for these increased levels are thought to be multi-faceted. Between 2019 and 2023, Ethiopia experienced an upsurge in conflict, the COVID-19 pandemic, a cost-of-living crisis and various climate related events. There have been decades of humanitarian response in Ethiopia, providing annual cycles of lifesaving interventions including the treatment of acute malnutrition in children under five years of age and the provision of humanitarian food assistance for the affected communities. Between 2013-2024, people in need of humanitarian support reportedly increased ten-fold with just 34% of the funding needs being met in 2023.5

Given the above, a central question for the Ethiopian Government has been this; with ever increasing population needs and limited resources, what can be done differently to bring about more lasting change through early recovery from crisis, mitigating the impacts of crisis and by preventing crises by addressing their structural causes. For too long, HDP efforts in Ethiopia, as with most crisis vulnerable countries in the world, whilst individually impactful, operate largely in parallel to one another. Humanitarian, Development and Peace (HDP) actors widely differ including their financing and operational modalities and although geographical and population targeting in some areas of Ethiopia may overlap, there is no mechanism for joint assessment and needs analysis to underpin joint planning and implementation. There is an absence of institutionalized coordination platforms, a lack of timely and quality information being exchanged and significantly, there isn’t an accountability mechanisms among HDP actors. Such ‘siloing’ of HDP actors means that the potential for greater impact through a collective effort is not being realised. For the Government of Ethiopia it is the realisation that we are failing to build more sustainable systems that deliver key services and interventions, and which mitigate the deleterious effects of chronic and repeated crises on rates of hunger, sickness and malnutrition.

Progress in nexus strengthening in other fragile settings

Two recent globally led evaluations and reviews of progress on a Nexus approach concluded that although there have been some improvements, progress has been uneven and very slow particularly with regard to joint analysis and programming, improved financing mechanisms and localisation of aid.6,7 Furthermore, these evaluations concluded that by and large the international community’s current crisis response model broadly maintains programming and financing as separate and segmented. Localisation, it is reported, seems to be stifled by an inability to adjust and match the management and instruments behind Official Development Assistance (ODA) and HDP Nexus approaches with the absorption, accountability and capacity of partner structures. For sustained capacity development and long-term impact, the authors argue that international agencies need to go beyond transactional and temporary forms of partnerships with national and local actors.

There are however examples of countries that have transitioned through HDP Nexus approaches involving decentralized government and decision-making and localisation of response culminating in national systems which are able to build resilience and prevent and mitigate the impact of recurrent shocks obviating the need for repeated humanitarian responses8,9 However, these examples are few and far between.10

There are also examples of better financing to support an HDP Nexus approach. The Irish governments aid instrument has established a new five-year funding scheme that enables partners to work across the Nexus and to move funds between development and/or humanitarian/chronic crisis funding streams when needed.

In Bangladesh, the Canadian government’s aid instrument has partnered with the World Bank to adopt an innovative financing mechanism to better support the health and basic education needs of the Rohingya refugees. The programme uses a phased and multi-sectoral approach to address the immediate and medium-term needs of displaced communities and the host communities in Cox’s Bazar.11

There is also a notable expanded role that international finance institutions (IFIs) and multilateral development banks are playing across the HDP Nexus as an increasing number of IFIs are tailoring their work to the needs of fragile contexts, with most development banks and the International Monetary Fund adopting fragility strategies.

Efforts are also being made to further integrate the peace component across the HDP Nexus, but these initiatives remain marginal partly because support to peace objectives includes a broad range of significantly different activities and mandates than that of the traditional humanitarian and development actors, and due to sometimes diverging understandings of what actions contribute to peace.

Good examples of peace activity integration into a Nexus approach include where the European Union (EU) and its member states established a “Political Framework for Crisis Approach in Eastern DRC”, As a result, EU services dealing with humanitarian, development, stabilisation and peace actions jointly identify areas of convergence. The Belgium governments aid instrument has been using a Fragility Resilience Assessment Management tool which allows agencies to identify priorities and modalities moving away from risk aversion to informed risk management. The tool was tested in 2018-2019 in Mali, Burkina Faso and the Democratic Republic of Congo to develop a risk matrix for more effective interventions with an acceptable risk level and weighing costs and benefits.12

The Ethiopia Nutrition Centric Nexus Approach

Recognising that the ‘business as usual’ approach is not working in Ethiopia, government has taken the first steps to change how national, sub-national and international actors work together to more effectively harness and utilise the human and financial resources that exist to reduce malnutrition.

A Nutrition Centric HDP Triple (NC-HDPT) Nexus approach was instigated with the development of an Operational Guide (OG) and Implementation Raodmap (IR).13 The OG and IR are the first ever national documents developed to provide guidance for how HDP actors can, through a Nexus approach, implement their interventions for improved nutrition outcomes in Ethiopia. These documents were informed by available global guidance and a national landscape analysis which captured the Ethiopian situation. The milestones, investments, collaboration frameworks and strategic actions that need to be in place to operationalise the NC-HDPT Nexus approach in Ethiopia were agreed and set out.

Developed over a one-year period, these key documents have involved leadership by two key line ministries (the Ministry of Health and the Ethiopia Disaster Risk Management Commission) in tandem with international development and humanitarian partners. The OG and IR for the NC-HDPT Nexus approach was officially endorsed by Government and disseminated on July 4, 2024. The conceptual framework for the NC-HDPT Nexus approach is shown in figure 2.

The changes that are sought through operationalizing the Nexus approach are as follows.

-

Reduced prevalence of stunting among children under five years of age

-

Increased household dietary diversity

-

Enhanced community resilience

-

Decreased incidence of conflict-related displacement

-

Sustainable increase in the participation of women and youth in local peacebuilding initiatives

-

Decline in inter-communal violence incidents reported

Targets for these indicators, as well as ‘process’ indicators which help monitor the adherence to, and implementation of, the NC-HDPN approach, are set out in the OG and IR although it is recognised that these will need to vary by region and in some cases by sub-region.

Moving from well informed words on paper to effecting real change

Government of Ethiopia will be operationalizing the NC-HDPT Nexus approach iteratively and will adopt a learning by doing approach in three crisis prone and highly vulnerable regions of Ethiopia (Afar, Somali and Tigray). Such an approach will require close monitoring of Nexus specific indicators and sub-national dialogue to understand what is going well and what isn’t. Nexus related activities will be intrinsically linked to the government and international donor funded flagship nutrition programme called the Seqota Declaration (SD)14 as this has already demonstrated significant impact on rates of child stunting and has used a ‘learning by doing’ model for implementation. The SD also provides the existing coordination, governance and community-based arrangements that can be harnessed for the Nexus approach.

Operationalisation requires working together to address existing coordination challenges and to collaborate to address vulnerabilities to crisis by going beyond the business-as-usual approach employing different programming approaches, funding models and overcoming the siloed implementation of humanitarian aid, developmental assistances and peace building actions.

To make real progress, we face significant obstacles to disrupting the 'business as usual 'ways of working and it is hoped that as with the roll out of the SD which gained traction through a ‘proof of concept’ approach, a similar approach with the Nexus approach will engender international agency alignment and support.

Summary of the NC-HDP Nexus OG and IR

There are seven strategic priorities to guide operationalisation.

-

Establishing nexus coordination and governance structures

-

Conducting joint context assessment and needs analysis

-

Developing and implementing scalable multi sector and multi-year resilience programming

-

Establishing multi-year and flexible financing mechanisms

-

Establishing a context specific and harmonized monitoring and evaluation framework

-

Embracing the localization agenda and local solutions

-

Integrating peacebuilding actions and conflict sensitivity

We believe that the OG and IR will serve to guide HDP actors in Ethiopia to compliment and synergise their interventions within an NC-HDPT Nexus approach for improved nutrition outcomes. This will help the HDP actors to engage in a ‘New Way of Working together’15 to overcome the traditional boundaries and converge efforts, align investments and create mutually reinforcing programmes that utilise limited resources more efficiently.

The minimum requirements and milestones included in the OG were designed through rigorous stakeholder consultation processes and are sufficient for Nexus operationalization to begin.

How the current system can be changed

The current status quo will not bring about sustainable or accelerated reductions in malnutrition in line with global and national targets. Ethiopia needs multiyear, multi stakeholder and multi sector actions implemented through a Nexus approach that strives for the achievement of collective HDP nutrition outcomes. Whilst donors and international actors must continue to uphold, support and protect humanitarian standards and principles, reducing the need for repeated humanitarian response is paramount as these cannot deliver the resilient systems and services needed to prevent malnutrition.

Furthermore, the Nexus approach will not succeed unless the amount of aid available to local and national organizations significantly increases in line with the Grand Bargain initial target of 25%. Donors and international agencies therefore need to increase the proportion of funding to local actors and ensure their capacities are strengthened, that they are empowered to engage in, and influence decision making processes and can lead local efforts.

The government needs to lead on increasing domestic and local resource mobilisation efforts through the development of a ‘domestic financing strategy’ to leverage external matched funding.16 This approach has been successful with Ethiopia’s large-scale safety net programme and is the approach being advocated to enable SD roll-out to more districts.

Currently, peace building efforts in Ethiopia are largely left to government sectors whereas more purposive engagement and inclusion of peace actors in the Nexus approach will be invaluable.

Change to the status quo will not be easy and there will be areas where resistance to doing things differently will need to be overcome. For example, for more resources to be allocated to national and local organisations, fewer resources will be available for international operations. Donors need to find ways to incentivize changes that enable a greater shift to local actions for example by making international actors agree to incremental increases in localisation targets and to put in place the accountability necessary for this shift. Government too will need to demonstrate a greater degree of fiscal and programmatic accountability and transparency at all levels with clear leadership at the Federal level and clarity on the measurable indicators for tracking implementation and change.

As so little concrete learning is available globally about operationalising a NC-HDPT Nexus approach, Ethiopia must endevour to actively share learning of what is working and what is not working as its statrts to operationalise the approach in crisis vulnerable areas of the country within the SD programme. Such evidence and learning will be invaluable within Ethiopia and in other crisis prone countries which confront many of the same nutrition related challenges.

In conclusion, institutionalizing the nexus coordination and governance structures, pitching for multiyear and multi sector resilience and risk mitigation nutrition programing, casting for flexible and multiyear financing mechanism for nutrition which is supplemented with domestic financing, deliberate empowerment of local actors and purposive engagement of peace actors at all levels are ‘a must to achieve’ operationalisation of this ‘New Way of Working’ in Ethiopia. This is how to improve the health, food and nutrition security of the Ethiopian people, build resilient systems, services and communities and mitigate the growing risks faced by climate change, conflict and other shocks. We need more joined up multi-sector actions that tackle the drivers of malnutrition. This is the Nexus approach we are seeking as the new paradigm in Ethiopia.

Funding

None.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the support of Irish Aid in the publication of this paper. The view expressed are those of the authors only.

Authorship contributions

All authors contributed to the manuscript.

Disclosure of interest

The authors completed the ICMJE Disclosure of Interest Form (available upon request from the corresponding author) and disclose no relevant interests.

Correspondence to:

Carmel Dolan

Director

N4D Transforming knowledge into action for nutrition & development

carmel@n4d.group