Background

Skilled birth attendants are defined as accredited health professionals such as midwives, doctors, or nurses who have been trained to be proficient in the skills needed to manage uncomplicated pregnancies, childbirth, and the immediate postnatal period (within 24 hours), in addition to the identification, management, and referral of women and neonates with complications.1,2 The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends all women have access to skilled maternity care during delivery at any appropriate place, from homes to tertiary referral centers, depending on availability and need.2 Increasing the proportion of births attended by skilled health personnel is an indicator of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG).3 However, only two-thirds (68%) of all births in low-income and 78% in lower-middle-income countries are assisted by skilled health personnel, compared to the almost universal (99%) coverage of skilled childbirth in high-income and upper-middle-income countries.4 In sub-Saharan Africa, the WHO projects that approximately 141 million births will take place without the assistance of skilled health personnel between 2022 and 2030.5

ANC plays an indirect role in reducing maternal mortality by encouraging women to deliver with a skilled birth attendant in a health facility.6 This provides an opportunity to counsel women on the advantages of giving birth in medically controlled conditions by skilled birth attendants in areas where the traditional birth attendant is common.7,8 Previous studies have found a positively significant association between births attended by qualified practitioners and high-frequency9,10 and content of ANC visits.6,11 However, there is also a high number of birth assisted by non-healthcare providers among women who received ANC.12

In Ethiopia, unskilled birth attendants or non-healthcare providers such as traditional birth attendants, relatives/friends, and other persons assisted childbirth account for half of the births, which might have contributed to the high maternal (267 per 100,000)4 and neonatal mortality rates (33 per 1,000 live births).13 Considering that most home deliveries are assisted by non-healthcare providers in Ethiopia, suggestive reasons why women opt for home delivery after ANC include; lack of knowledge about health facility delivery, poor counselling during ANC services, the availability of traditional birth attendants (TBA), poor access to healthcare facilities, and inadequate resources.14,15 However, the reasons why women opt for home delivery might differ from why they choose to be assisted by a non-healthcare provider such as a TBA. This study aimed to identify the determinants and geographical distributions of non-healthcare provider-assisted childbirth after having ANC visits in Ethiopia. Examining these factors can be useful to health care providers, maternal health policymakers, and global health advocators in addressing the unacceptable high level of maternal mortality in Ethiopia.

Methods

Data source and study setting

We conducted a secondary analysis of the most recent 2019 Ethiopian Mini Demographic and Health Survey (EMDHS).16 Ethiopia is Africa’s second most populous country, with a population exceeding 123 million in 2022 of which nearly half (49.8%) were female.17 Currently, Ethiopia is federally decentralized into twelve regions and two city administrations.18 However, three new regions (Sidama, Central Ethiopia and Southwest Ethiopia) were under the Southern Nations Nationalities and Peoples’ (SNNPR) region during this survey.18

Sample size and Sampling

The 2019 Ethiopian DHS used a two-stage stratified sampling design using the 2007 Ethiopian population and housing census as a sampling frame. Each of the nine regions and Dire Dawa city administration was stratified into urban and rural areas, yielding 21 sampling strata. In the first stage, there were a total of 305 clusters of Enumeration Areas (EAs). However, for this study two clusters from rural parts of the Somali region had no records of ANC visits and were therefore removed from the analysis. In the second stage of selection, a fixed number of 30 households per cluster were selected with an equal probability of systematic selection after listing households.16

Women who had a birth within 5 years and received at least one ANC visit were the study participants. Of the 5,753 women who gave birth in the five years preceding the survey, only 3,979 women with recent births were asked about their uptake of ANC services. Among them, women who did not receive ANC services (1,044) and those who were unsure whether they received ANC services (17) were excluded from the analysis. All analyses were conducted by applying sample weighting to account for probability sampling and non-response, thereby restoring representativeness. Finally, 2,918 samples (2,913 weighted samples) were included in the analysis (Supplementary Figure 1).

Definitions and measurements of variables

The outcome variable is childbirth assisted by non-healthcare providers, which included births attended by traditional birth attendants, relatives/friends, and other persons who are generally considered as unskilled birth attendants and non-assisted childbirth.19,20 We considered individual and community-level factors. The individual-level factors included socio-demographic characteristics such as age, education status, marital status, wealth index, and religion. Health service utilization related factors such as quality and frequency of ANC visits, place of delivery, and child-related determinants such as birth order and the number of children aged under five years in the family are included in the study. Moreover, community-level variables such as place of residence, administrative region, and community-level women illiteracy were also considered. These variables were considered based on previously published literature and the availability of information in the dataset (Supplementary Table 1).

Statistical analysis

The DHS data has a hierarchical nature such that reproductive-aged women were nested within a cluster. This might violate the standard logistic regression model assumptions such as the independence and equal variance assumptions. Therefore, a multilevel binary logistic regression was fitted with three models: Model I (null) with only the cluster-level random intercept, Model II with the random intercept and individual-level variables, and Model III with both individual and community-level variables plus the random intercept. The measure of variation or random effects was estimated by the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC), median odds ratio (MOR), and proportional change in variance (PCV). The ICC result reveals that 48% of the variation in having birth assisted by non-healthcare providers was due to cluster variation. The MOR is defined as the median value of the odds ratio of births assisted by non-healthcare providers between the area at the highest risk and the area at the lowest risk when randomly picking out two clusters (EAs)21–23 which was 5.17 (95% CI: 4.11, 6.78) in our first model. Moreover, the PCV in the final model (model three) reveals that about 42.14% of the variation in births assisted by non-healthcare providers was explained by the included factors. The deviance test was used for model comparison, and the model with the lowest deviance (Model 3) was considered the best-fit model (Supplementary Table 2).

Spatial analysis

To assess spatial autocorrelation, the Global Moran’s I statistic was used.24 The Global Moran’s I value ranges from −1 to +1, where a value below 0 indicates negative spatial autocorrelation and values above 0 indicate positive.24,25 Whereas a spherical semivariogram ordinary kriging type spatial interpolation technique was used to predict the non-healthcare provider’s assisted childbirth for unsampled areas based on sampled clusters. The proportion of women who had non-healthcare provider assistance during childbirth in each cluster was taken as input for spatial prediction. Bernoulli-based modelled spatial scan statistics were used to identify the locations of clusters of non-healthcare provider-assisted births.26 The scanning window moved across the study area, with women assisted by non-healthcare providers during childbirth considered as cases, and those without such assistance as controls to fit the Bernoulli model.

Missing data handling

The missing values were clearly defined by the DHS guideline. Women who answered “don’t know” and had missing data for the antenatal check were recoded into a category for no ANC dataset.27 There were 17 “don’t know” answers for ANC visits which were excluded from the denominator. However, there was no missing value for the record of delivery attendance for those women who received at least one ANC.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of women

From the total 2,913 women, more than half (53%) were between 25–34 years, with a median age of 28 years (interquartile range (IQR) = 8 years). Almost half (46%) of the women had no formal education. Approximately three-fifths (60.6%) of the women lived in communities with low female literacy levels. Moreover, about one-third (33.8%) of the women were from low-income households. Only less than one-third (29.7%) of children were from urban (Table 1).

Contents of antenatal care services in the EMDHS survey

The proportion of women who received all six essential components of ANC in Ethiopia was 36% (95% CI: 34.1% to 37.6%). Of the six essential components, blood pressure measurement was the most (88.1%) commonly provided service, whereas counselling about pregnancy complications was relatively the least (60%) provided services (Figure 1).

Assistance during childbirth among women who received antenatal care in Ethiopia.

The proportion of women whose births were assisted by non-healthcare providers was 33% (95% CI: 31, 35) and ranged from 1% in Addis Ababa to 46% in the Afar region. TBA were the most common (18%) unskilled childbirth attendants during childbirth (Figure 2).

Among all births that occurred at home, only 9% were assisted by healthcare providers. In addition, two-fifths (40.7%) of women who received poor quality ANC services were assisted by non-healthcare providers as compared to women who received good quality ANC services which are one-fifth (22%). Moreover, more than two-thirds (67%) of women who had one ANC visit had a non-healthcare provider-assisted childbirth as compared to women who had four and more ANC visits (24.3%).

Determinants of non-healthcare providers’ assisted delivery among women after getting ANC

After adjusting for all the independent variables, individual level variables such as education status of women, wealth index of the household, quality of ANC services, number of ANC visits, birth order of the child, and community level variables such as residence and administrative region, and women literacy status were statistically significant variables.

Women with primary education and secondary or above education had 44% (AOR=0.66; 95% CI; 0.52, 0.85) and 66% (AOR=0.44; 95% CI; 0.29, 0.68) lower odds of having non-healthcare providers assistance during childbirth compared to women without formal education. Moreover, women from high-community literacy clusters had 65% lower odds of being assisted by non-healthcare providers than those from low-community women’s literacy status (AOR=0.35; 95% CI; 0.20, 0.59).

Women who received poor quality ANC visits (AOR=1.74; 95% CI; 1.38, 2.20) and had only one ANC visit (AOR=5.2; 95% CI; 3.19, 8.63) had higher odds of receiving childbirth-assisted by non-healthcare providers compared to those having good quality ANC visit and four and more ANC visits respectively. In addition, the odds of assistance by non-healthcare providers among women who delivered their 2nd and 3rd child were two and three times higher than those women with 1st birth (AOR=2.17; 95% CI; 1.48, 3.19) and (AOR=3.50; 95% CI; 2.33, 5.28) respectively. Women from middle and high household wealth quintiles have 40% and 59% lower odds of being assisted by non-healthcare providers than women from low wealth quintiles (AOR= 0.64; 95% CI; 0.45, 0.80) and (AOR= 0.41; 95% CI; 0.30, 0.45) respectively. In addition, the odds of being assisted by non-healthcare providers among women who resided in rural areas and communities with predominately pastoralist regions are 3 times higher than their counterparts (AOR=2.93; 95% CI; 1.44, 5.93) and (AOR=3.38; 95% CI; 1.05, 11.32) respectively (Table 2).

Geographic analysis of non-health provider assisted childbirth among women who have at least one ANC visit in Ethiopia

Spatial autocorrelation and hotspot analysis

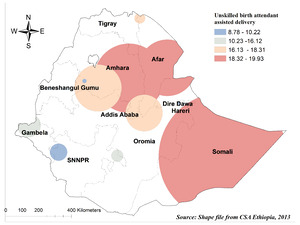

Having unskilled delivery assistants at birth in Ethiopia showed significant positive spatial autocorrelation over regions in the country. They were found to be clustered with Global Moran’s Index values of 0.5 with p< 0.001 (Figure 3). The hot spot area for unskilled delivery assistance during birth was shown in the Southern part of Amhara, Eastern parts of Afar, Somali, and at the border between Oromia and SNNPR regions. However, Addis Ababa, Dire Dawa, and the western part of Benishangul Gumuz regions were the cold spot regions for unskilled delivery assistants during birth (Figure 4).

Spatial scan statistics and interpolation analysis

The SaTscan analysis result showed that 61 primary clusters were detected for having unskilled delivery attendants during birth among women who received ANC in Ethiopia. There are multiple overlapping primary windows for unskilled delivery attendants during birth, and they are predominantly located in the Somali, Afar, and Amhara regions (Figure 5). Women who were found in the primary window area were 2.77 times more likely to have unskilled birth attendants than out in window regions (RR= 2.77, P-value<0.001) (Supplementary Table 3, Figure 5).

The Kriging interpolation methods of predicting unskilled delivery attendant-assisted birth were predicted in Somali and Oromia regions and ranged from 58.5% to 73%. However, the lower risk predicted area ranges from 0-15% and is predicted in Addis Ababa, Dire Dawa, and Benishangul Gumuz regions (Figure 6).

Discussion

Even though one of the main goals of ANC is to facilitate women’s decision to seek skilled birth attendants,8,28,29 we found that only 33% of women (95% CI: 31%, 35%) gave birth with the assistance of a non-health provider after having an ANC visit. However, regional disparities were observed in the proportion of births attended by non-health provider attendants, ranging from 1% in Addis Ababa to 46% in the Afar region, and had a nonrandom spatial variation across the country. The proportion of births attended by non-health provider attendants also ranged from 24% for women who had focused ANC visits to 67% for those women who had only one ANC visit.

The proportion of women delivered by non-health provider birth attendants in our study was higher than a study in Debre Berhan town, central Ethiopia, that showed only 0.5% of women drop out from skilled birth attendant delivery after having focused ANC visits.30 This difference is not unexpected as the study in central Ethiopia included urban resident women who have better access to health facilities and better health-seeking behaviours. However, our analysis included national data, including data from geographic areas, where access to health facilities is limited and cultural practices are predominant. Moreover, the latter study focused on women with ANC (four or more ANC visits), unlike our study, which includes women with at least one ANC visit. This study is also higher than the UNICEF 2022 report, where only 14% of women globally and 30% of women in sub-Saharan Africa delivered by non-skilled health professionals regardless of their ANC visits.5 The socio-cultural difference in healthcare utilization and the large presence of unskilled birth attendants in the low economic countries such as Ethiopia might have contributed to this high proportion of births attended by non-healthcare provider.31,32 The presence of TBAs and family provides physical, social, and emotional support during childbirth.14 Moreover, the low health worker density may affect waiting time and discourage women from further utilizing maternal health care services. For instance, in 2018, Ethiopia’s health worker density was estimated at 1.0 per 1,000 population, which is significantly lower than the WHO’s recommended standard of 4.5 per 1,000 population needed to achieve universal health coverage (UHC).33

In this study, blood pressure measurements were more commonly reported as essential components of ANC service than other aspects, such as counselling about pregnancy complications. This finding is consistent with another study in Ethiopia.34 A possible explanation could be that counselling about pregnancy complications may be prioritised for women who were deemed to have high-risk pregnancies. Furthermore, unlike information sessions, measurements such as blood pressure may be easier for women to recall and report during surveys.

Women with formal education and from clusters with high women literacy levels have lower odds of having unskilled birth attendants during delivery than women without formal education. This is in line with studies from Ghana35 and Nigeria31 that showed women with no education had higher odds of using unskilled birth assistants during delivery. This may reflect that women with higher levels of education are more responsive to health-promotion messages36 and have the financial capacity for travel arrangements to arrive at health facilities where skilled health attendants provide delivery services.37,38 It is also possible that educated women are less likely to be persuaded by cultural paradigms that may encourage the use of unskilled birth attendants.31 Moreover, in our study, we found that women from middle and high-household wealth quintiles have lower odds of delivering by unskilled birth assistants than women from low-wealth quintiles. This is supported by studies from Ghana,35 Nigeria,31 and India,39 which stated that economic status had an impact on health services use. A possible explanation could be that even though delivery service is exempted (free of charge) in Ethiopia, women who reside in poorer households mostly reside at a distance from accessing health facilities and are uneducated, and this may result in women choosing home delivery with the assistance of unskilled birth attendants.31,40 This shows that women’s empowerment by enhancing their capacity through financial and literacy levels is important to making purposive choices and healthcare decision-making.41,42

We found that women who had only one ANC visit had higher odds of being delivered by unskilled birth assistants compared to those having four or more ANC visits. This is supported by studies from Nigeria40 and Bangladesh43 that showed women who had frequent ANC (≥4) visits were less likely to be assisted by unskilled birth attendants. A study conducted in rural India also found that women who received at least 75% of the nationally recommended ANC services had significantly higher odds of skilled institutional delivery.39 This suggests that the women’s decision to receive assistance from skilled birth attendants is increased through subsequent ANC visits. A probable cause could be that in the fourth ANC visit, birth preparedness and counselling about the health institution delivery and transportation options is one component.44 Furthermore, our study found that women who had poor-quality of ANC visits had higher odds of unskilled assistants during delivery compared to their counterparts. Studies also showed that women who obtained higher levels of ANC were more likely to use safe delivery care than those with lower ANC levels.6,39 Effective communication about the risks of home delivery by providers could explain this association.45 Moreover, when quality care is provided, women become comfortable with the health system and providers.45 This indicates that health providers should adhere to the guidelines to deliver quality ANC care for women which eventually leads to increase utilization of skilled delivery assistance during birth.

Additionally, this study found that the odds of being delivered by unskilled birth assistants among women who delivered their 2nd and 3rd child were higher than the 1st child. This is supported by a study in India39which showed that women experiencing their first birth were much more likely to obtain professional health care at delivery. A study from Bangladesh also showed that multiparity was a strong predictor of unskilled birth attendant delivery.43 This might be related to factors such as excitement and fear of the unknown over a first child.39 The problems experienced during the previous delivery in the health facility would be expected to affect increasing unskilled delivery assistance.39

In our study, the odds of delivering by unskilled birth assistants among women who resided in rural areas or communities with predominately pastoralist regions were higher than their counterpart urban, or Metropolitan respectively. This is supported by other studies.31,46 This finding could be explained in different ways. First, rural residents adhere more to cultural norms, which may contribute to the use of unskilled birth attendants, such as traditional birth attendants and families’ assistance during delivery.47 For example, a quantitative study showed unskilled birth attendants were relatively high in rural (25.8%) as compared to urban (12.5%).31,32 Second, rural residences have so many different types of barriers to accessing skilled birth attendants, such as long-distance to health facilities, lack of transportation, and low socio-economic status.47,48 This is because women might come for ANC visits with appointments, however, they might face difficulty for skilled delivery assistant birth since it is not mostly with scheduled birth.

In our study, unskilled birth attendants had spatial variations across the country, and this did not occur by chance. The hotspot cluster analysis identified the concerned districts as Eastern parts of Afar, Somali, Southern, and Southwest parts of Amhara and at the border between Oromia and SNNPR regions. Our finding is supported by studies from Sub-Saharan Africa,37 Ghana,35 and Bangladesh43 which showed that unskilled birth assistance used during delivery has a spatial dependency. This means that although the use of maternal health services from non-healthcare providers during childbirth in Ethiopia is a complex issue, regional variations exist, which is consistent with a study in Sub-Saharan Africa.37 These variations could be due to the physical inaccessibility of health institutions and skilled birth attendants, and residents adhere more to cultural norms47 and several socio-economic hardships which have especially in predominantly pastoral regions49 This was reflected in a qualitative study, which indicated that the hard-to-reach, pastoral nature of some kebeles in the study area led to the assignment of male health extension workers (HEWs).50 To reduce reliance on non-health provider birth attendants and improve maternal health outcomes, targeted interventions that expand healthcare infrastructure and improve access in underserved areas are essential. By addressing these spatial barriers, we can move closer to achieving equitable maternal health across the region.

Limitations

Even though we used nationally representative DHS data, certain limitations should be considered. Since the data were collected cross-sectional by self-reported interview, there was a potential for social desirability bias. Given that the study includes women who delivered in the last five years before the survey and asked about the essential service they provided, there might be a recall bias for earlier deliveries. Furthermore, while the essential components and frequency of ANC are included, the quality of each component of care in terms of depth and breadth of information provided was not recorded in the data. Another limitation is the lack of data on health provider and health system-related factors and information for the skilled birth attendance for earlier births, which makes it difficult to fully understand the supply-side factors that may lead women to opt for non-health provider-assisted childbirth after receiving ANC.

Recommendations

Health interventions should focus on improving the provision of quality and comprehensive ANC services to prevent non-healthcare provider-assisted births. This can be achieved by developing a checklist of essential components of ANC for each visit, which can help healthcare providers’ adhere more effectively to the recommended ANC components. Women’s empowerment through financial resources and education needs be the priority focus of the government of Ethiopia. Large scale media campaigns and community outreach services should be implemented to enhance women’s health literacy and empowerment. Regions such as Afar, Somali, and Amhara regions should be focused on and set strategies for the interventions of the high proportion of births assisted by non-healthcare providers in the area. Future research could address these limitations by incorporating longitudinal designs, exploring supply side factors, and employing a mixed-method study approach.

Conclusions

The proportion of women who used non-health providers during childbirth after ANC booking in Ethiopia was high compared to WHO recommendations. Higher odds of non-healthcare providers’ assisted birth were reported by women who had only one ANC visit, and in those who live in pastoral communities and rural areas. Whereas lower odds of childbirths assisted by non-healthcare providers were experienced by women with secondary or above education, being from wealthier households, and women who took all six components of ANC. Moreover, the spatial distribution of unskilled birth attendants used during delivery was not random and more practiced in Somali, Afar, and the Southwest part of Amhara and at the border between Oromia and SNNPR regions.

Acknowledgements

The Measure DHS Program is to be commended for supplying the dataset.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was not required for this study as we used a secondary analysis of a publicly available survey from the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) program.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Availability of data and materials

The data used in our study are from the 2019 Interim Ethiopia Demographic, and Health Survey and can be requested from the MEASURE DHS available at https://www.dhsprogram.com/Data using the details in the methods section of the paper.

Funding

This research did not receive specific funding. GAT reports a grant from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (# 1195716) during the conduct of this study. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Authors’ contribution

DGB and, MB, TGH contributed to led conceptualisation, design, analysis, and interpretation and wrote the article. GAT, RN, JD, MBA and TGH contributed to the design and critically reviewed subsequent drafts of the manuscript. All authors have contributed to and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors completed the ICMJE Disclosure of Interest Form (available upon request from the corresponding author) and disclose no relevant interests.