For several years, the nutritional situation in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) has remained worrying.1 Malnutrition due to macronutrient deficiency remains the most common and consists of insufficiency in a person’s energy and/or nutritional intake and covers three large groups of conditions including emaciation (low weight/height ratio), retardation growth (low height/age ratio) and underweight (low weight/age ratio).2

According to the MICS 2018 survey, among children under 0-59 months, 41.8% suffer from stunted growth, 23.1% are underweight, and 6.5% children suffer from acute malnutrition, including two per cent in the severe form.2 In the Tshuapa province, 32.9% of children under 5 years old are underweight, 49.2% are stunted, and 13.6% have global acute malnutrition.3 Among these prevalences which are above the thresholds, there are strong disparities in the different forms of malnutrition within the province.2,4–6

Having benefited from interventions with the implementation of a package of activities including activities to support governance, management of acute malnutrition, actions to ensure dietary diversity and management of nutritional emergencies. This aims to reduce the prevalence of different forms of malnutrition with technical support from United Nations Chilldren Fund (UNICEF) and financial support from the World Bank since 2019. Several interventions have been carried out by international organizations, notably the implementation of community-based nutrition, and the promotion of Protocole National de Prise en Charge Intégrée de la Malnutrition Aiguë (PCIMA); despite all the funds allocated, the nutritional status of children under 5 years old has not improved for several years like the last nutritional survey.

At the end of these interventions, a Smart territorial nutritional survey was carried out in this territory to assess the effects of these interventions. Despite these different strategies and multiple interventions implemented, despite the efforts made by the Government of the Democratic Republic of Congo, the nutritional situation in the province of Tshuapa, particularly in the territory of Befale, continues to worsen.5,6 Befale is the territory of the Tshuapa province, this province has one of the highest prevalences of malnutrition in the country and had benefited from nutritional interventions with the implementation of a package of activities aimed at reduce the prevalence of different forms of malnutrition with technical support from UNICEF and financial support from the World Bank through the PDSS since 2019.

It should be noted that food prices have increased following armed conflicts in this province.7 Knowing internal disparities is important for decision-makers to better adapt their interventions. The present study aims to determine the prevalence and identify the factors associated with these disparities of different forms of malnutrition among children under five years old in Befale.

METHODS

Study location

Befale is located in the province of Tshuapa; the population is involved in agriculture, hunting, traditional fishing, and breeding to generate agricultural products (cassava, corn, plantain, local rice, peanuts), non-agricultural products (meat, fish, caterpillars, wood, oil) and manufactured for household survival and small business. More than 35% of the population of this territory lived in food insecurity in phase 3 and above from July to December 2023, caused by intercommunity conflicts, the displacement of populations following conflicts, climate disruptions, attacks by crop pests and epizootics, and the very dilapidated state of agricultural service roads.

Sampling

The National Nutrition Program (PRONANUT) gathered data from children in the Befale territory between the ages of 6 and 59 months in 2022, which was used in this cross-sectional study. A two-stage cluster survey employing the SMART (Standardized Monitoring and Assessment for Relief and Transition) approach was used to conduct the survey among a subset of households. The SMART approach in the survey was used on the recommendation of the national nutrition program in order to have standard data. This secondary data was used in collaboration with the program to identify the factors underlying malnutrition in the country. At the first level, the statistical units were villages/localities, and at the second level, households. Out of the 63 villages, 52 villages were chosen at random. In each village, 25 households were chosen, and all of the children under the age of six to fifty-nine months a total of 1088 children were taken from the households.

Outcomes

Nutritional indices were used to determine the nutritional status. Underweight was indicated by weight for age, stunting by height for age, and acute malnutrition by weight for height. The severity of the disease was indicated by the Z-Score, which was computed using the Emergency Nutrition Assessment (Ena) software version 2007. Global malnutrition (including moderate and severe malnutrition) was defined as a Z-score of less than or equal to -2 for all indices and severe malnutrition was defined as a Z-score of less than -3.

Data collection

Data was collected through smartphones using Kobocollect software and was stored in the national program server. The secondary data used have received authorization from the program which gives them to us directly through its storage system.The data were collected by investigators recruited and trained by the national nutrition program, the data was sent after processing by supervisors to the program server.

Analysis

The age, sex, weight, height, and associated illnesses of the subjects during the previous two weeks were described using descriptive statistics. The frequency of global and severe acute malnutrition, underweight, and stunting was also determined. The predictive factors were inspired by the UNICEF model. The independent variables relating to the child included age, sex, age, weight, height of subjects, and associated illnesses in the last two weeks (presence of diarrhoea, cough and malaria) to verify whether these factors should really have an influence on malnutrition. Inferential statistical analysis was performed using Pearson’s chi-square, odds ratio (OR) and 95% Confidence Interval (CI). The explanatory variables included in the logistic regression models were selected by a stepwise procedure.

Ethics

The main study protocol was submitted and approved by the ethics committee of the Ministry of Health. The protocol of the present study was submitted and approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Public Health of Kinshasa under number ESP/CE/71/2024.

The samples in the initial study were taken with the free and informed verbal consent of the parents of each child, after a brief explanation of the aim of the study. The data were analyzed without identifying the subjects investigated to preserve human dignity.

RESULTS

Overview

In this study, out of 1088 children surveyed, 77.8% of children were aged 24 to 59 months with the median age at 47 months (interquartile range, IQR: 28), the median weight was 12.6kg (IQR: 3. 7), the median height was 92.2 cm (IQR: 13.3), the median MUAC was 136 mm (IQR: 18) and the girl/boy sex ratio was 1:1.

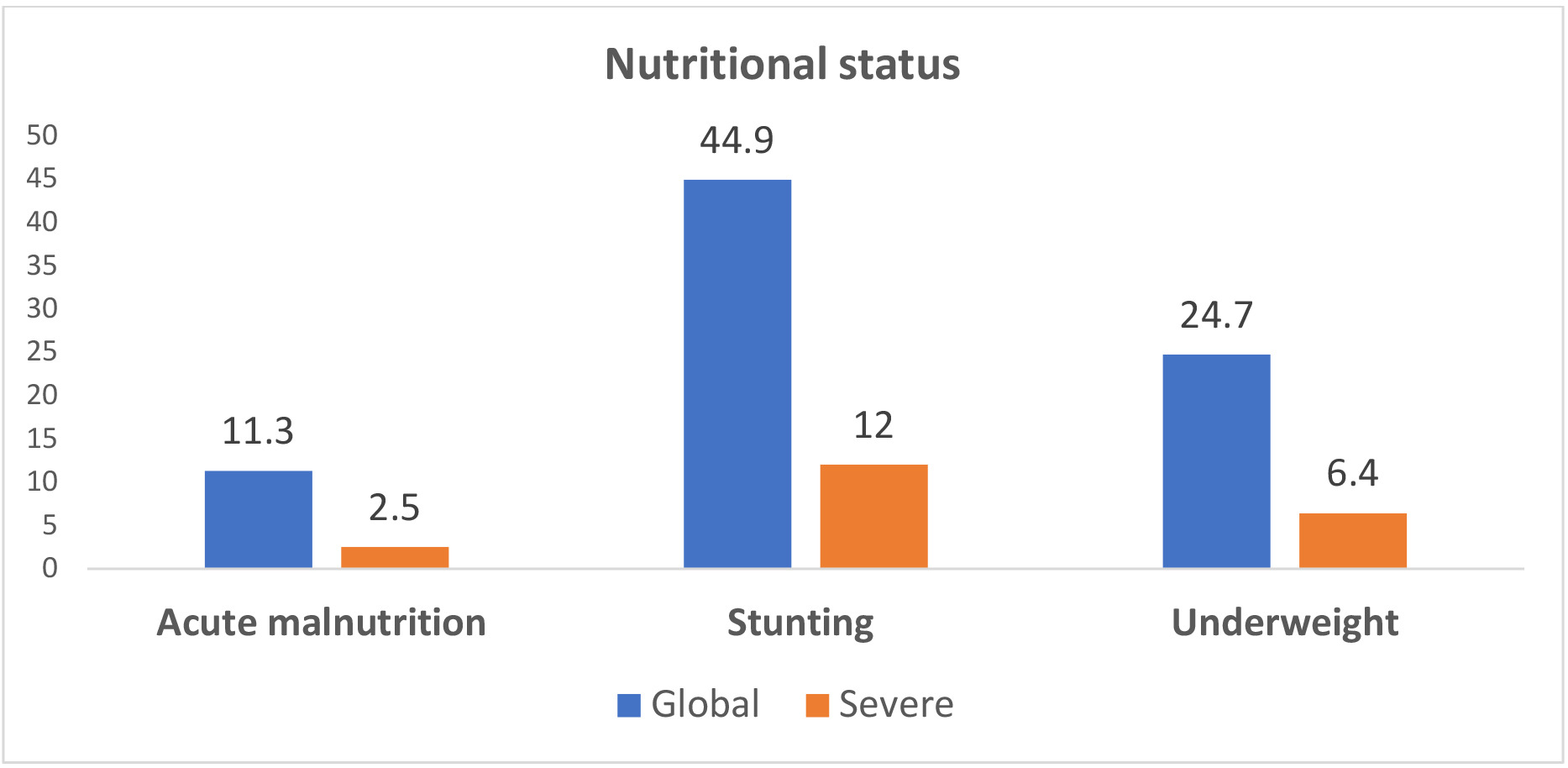

In the Befale territory, there is an uneven geographical distribution of various forms of malnutrition. With 11.3% of children impacted, the prevalence of global acute malnutrition was higher than 10%. At 44.9%, stunting was higher than 40% and affected every village, with a prevalence above 40% in 76% of them. The underweight rate was 24.7%.

The prevalence of various forms of malnutrition was higher in children between the ages of 24 and 59 months, especially in girls. Stunting and underweight were the most common causes of malnutrition.

Prevalence of different forms of malnutrition in the Befale territory

The prevalences of different forms of malnutrition are presented in Figure 2.

According to this figure, one in ten children suffered from global acute malnutrition, and among them, 2.5% of children presented severe acute malnutrition in Befale. Four out of ten children had stunting and almost a quarter of children were underweighted in Befale.

Sociodemographic characteristics

The sociodemographic characteristics concerned the age and sex of the children. The results showed that 77.8% of the children were over 24 months old while the youngest were fewer in number. The sex was proportionally represented with a ration boy/girl 1:1

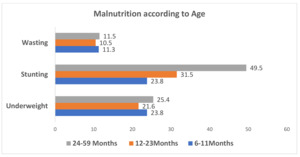

The malnutrition according to age of children aged 6-59 months in Befale are presented in Figure 3.

According to the results of the survey carried out among children under five years old, among the three forms of malnutrition, children aged 24 to 59 months were the most affected by underweight, stunted growth and emaciation in Befale.

The malnutrition according to Sex of children aged 6-59 months in Befale are presented in Figure 4.

It has been noted that all forms of malnutrition, including underweight, stunting and wasting, affect the male sex.

Regarding the prevalence of malnutrition, the results reveal that children in ten suffered from global acute malnutrition, and among them, 2.5% of children presented severe acute malnutrition in Befale. Four out of ten children suffered from stunted growth and almost a quarter of children were underweight in Befale.

This table 2 shows that the children with the age between 24-59 months was more affected by the three forms of malnutrition and all forms of malnutrition affected the male sex more.

The use of the chi-square test at the 5% threshold revealed a statistical association between the age of the children and stunting and a statistical association between sex and all forms of malnutrition.

History of illness

Wanting to verify the relationship between the different illnesses suffered in the two weeks preceding the survey, the Chi-square test revealed no statistical association between the presence of diarrhea, cough and malaria and the occurrence of malnutrition in Befale.

The illness history of malnourished children in Befale is shown in Table 3.

Factors associated with different forms of malnutrition

No factor was statistically associated with global acute malnutrition; the female sex was 1.6 times more likely to develop stunting, the age between 6-11 months was 2.6 times more likely, and the age between 12 -23 months exposed to 3.7 times developing stunting in the territory of Befale. No factor was statistically associated with underweight (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

Summary of findings

The study’s findings demonstrated that 2.5% of the children in Befale suffer from severe acute malnutrition, accounting for one in ten cases of worldwide acute malnutrition. Nearly 25% of children were underweight, and four out of ten had stunting. Among the implicated factors, stunting in children aged 6-59 months in Befale was found to be associated with female gender and age between 12-23 months.

Finding in the context of the literature

Comparing the prevalence of global acute malnutrition in this study and those of MICS 2018 ,2 which was 10.6%, and also those of the National Nutrition Survey 2023,3 which were respectively at 10.4% and 13.6%, we note always this form above the 10% threshold. Stunting of 44.9% in Befale was above the emergency threshold of 40%. Compared to the EDS1 whose prevalence was 38.2% in Tshuapa, and to MICS at 45.3%, we note variations in the prevalence of stunting in Tshuapa. In ENN 2023, stunting was at 49.2% in Tshuapa. Following the variation in these prevalences from 2014 to 2023, we noted an increase of 11% including 4.3% from 2022 to 2023 in this province. Underweight was on alert, 24.7% in Befale. In the National Nutrition Survey, the prevalence of underweight was 32.9% in Tshuapa. If we consider the prevalence of underweight from the 2014 EDS and that from the ENN2023, we noted an increase of 13.5% including 8.2% from 2022 to 2023 in Tshuapa.

Furthermore, if we took into account these prevalences from national surveys (EDS, MICS, and ENN 2023) separately, ours might be higher because, in this context, nutritional care is practically nonexistent, there is occasionally an unstable local economy, healthcare is breaking down, and household living conditions are getting worse.

In view of all these results, the nutritional situation in Befale remains catastrophic and this requires the involvement of all categories of the population and at different decision-making levels to put efforts together in the fight against this scourge. It is also important to strengthen the capacities of providers and actors on the promotion and protection of optimal Infant and Young Child Feeding (IYCF) practices throughout the 1000 days (from pregnancy to two years of age), as well as the implementation of the NAC based on a good community diagnosis.3

There is a disparity in the prevalence of different forms of malnutrition between the different villages of Befale. Considering the villages, the lack of temporality in this type of study is a factor limiting or preventing the establishment of a cause-and-effect relationship for the factors and prevalences.

It should be highlighted, nevertheless, that these discrepancies may stem from the socioeconomic differences of the various villages found in each territory, particularly from various causes of food insecurity and the insufficiency of numerous systems for handling malnutrition cases in these impacted villages. These differences may be caused by the inaccessibility of agricultural tracks, the inadequacy of agricultural production, the lack of use and unavailability of some inputs distributed in the various Nutritional Outpatient Treatment Unit (UNTA) and Intensive Nutritional Treatment Unit (UNTI) required in the management of cases of malnutrition, and the fragility of the local economy. These differences should be investigated in a different study because this one is not causative.

On factors associated with inequalities, it was noted that female gender and age between 12-23 months were associated with chronic malnutrition among children aged 6-59 months in Befale. These findings contrast with those of Mudekereza8 and Fentaw,9 who assessed the prevalence of malnutrition, and the risk factors linked to it. They discovered that 8% of children showed signs of wasting, and 34.7% of children showed signs of stunting, indicating a combination of wasting and stunting. According to their research, many children over the age of 12 months suffer from acute malnutrition, which peaked between the ages of 12 and 23 months (17.4%). On the other hand, stunting affects nearly half of children over the age of 12 months and occurs between the ages of 7 and 11 months (20.5%).

Stunting rises quickly with age, starting at 15% in children under six months and reaching 28% in those between 9 and 11 months, with a maximum of 54% in children between 36 and 47 months, according to the 2014 EDS. Male children are slightly more likely to suffer from stunting (45% vs. 40%), and stunting is more common in rural than in urban areas (47% vs. 33%).1 This requires a nutrition policy based on multi-sectoral strategies, oriented towards specific age groups most affected to reduce this burden and thus reducing child mortality.

For Hallgeir Kismul,10 stunting was much higher in boys than in girls, contrary to our results. Further research may be needed to find evidence of the role of sex in the genesis of malnutrition in children aged 6 to 59 months.

The idea that illnesses within the last two weeks have no bearing on malnutrition, as this study has demonstrated, may be explained by the fact that a delayed diagnosis of malnutrition significantly changes the nutritional status of children, making it difficult to determine what causes what when it comes to malnutrition. These findings contrast with those of Mwadianvita,11 who examined the incidence of malnourishment and HIV prevalence in children between the ages of 6 and 59 months in Lubumbashi. Their findings showed that chronic malnutrition, underweight, and wasting were linked to advanced HIV infection.

A bacterial, viral, parasitic, or fungal infection and unstable living conditions can directly lead to malnutrition. The disease progressed, and the clinical signs worsened in infected subjects with one or more nutritional deficiencies, changing the subjects’ nutritional status. In our opinion, every child who contracts an infection should be monitored from diagnosis until they recover, and their nutritional status should be evaluated as the illness progresses.12

When observing and assessing children during preschool consultation sessions, the various nutritional units should consider this factor by offering clear instructions and, if feasible, scheduling an early appointment for a follow-up developmental dietary assessment. However, finding explanations for some of the results was not possible due to limitations associated with the lack of specific information necessary for this study, precisely the outcome of the diagnosed children, the sociodemographic information, and the food security data of the children’s parents. The idea that the illnesses of the past two weeks are unrelated to malnutrition, as this study has demonstrated, may be explained by the fact that children’s nutritional status is significantly altered by the delayed diagnosis of malnutrition, creating a false sense of cause and effect in cases of undernourishment.

Study limitations

This study draws its strength from its high, representative sample size, the results of which can be generalised to the entire population of Befale or even in the province. However, the constraints linked to the lack of specific information adequate to this study, particularly the fate of the diagnosed children and specific socio-demographic, socio-economic and food security data of the children’s parents, did not make it possible to find explanations for particular results. It demonstrated the barriers to effective implementation of nutritional interventions that must consider each geographic context, the specific age of children and the affected gender.

In the future, we wish to approach this same research and direct it towards causal aspects, including food security, eating habits, socio-ecological characteristics, and the different morbidity factors influencing this nutritional state. This could contribute to a better geographical distribution of resources during nutritional interventions implemented by the National Nutrition Program and the various partners working in the field of nutrition.

Conclusions

To help lower mortality linked to malnutrition in Befale, the National Nutrition Program and other researchers identify and raise awareness of additional factors of food insecurity, dietary practices that can be the focus of health promotion projects, and nutritional education. Considering socio-ecological variables, the child’s age and gender are useful in directing the various approaches to address underweight and chronic malnutrition. It is possible and feasible to improve the management of malnutrition with each intervention put into place, taking into consideration the particular age and sex of the affected children within each village, territory, or province, as well as each local context. The best way to prevent stunting and underweight in children is to take actions that are tailored to their age and gender. The findings of this investigation continue to be a valuable resource for the National Nutrition Program and other scholars in their efforts to increase public awareness of and pinpoint additional causes of food insecurity.

Acknowledgements

The manuscript is part of the Master of Public Health thesis supervised by MCM.

Author contributions

BKN designed the entire study, conducted the data collection, and wrote the first draft. MCM supervised and checked for intellectual content.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)