The National Information Platform for Nutrition (NIPN)1 initiative was launched by the European Union (EU) in 2015, with support of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Foreign Office (FCDO) and Bill and Melinda Gate Foundation (BMGF). It aims to strengthen the capacity of the Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) Movement2 countries with a heavy malnutrition burden to make more use of multisector nutrition data to inform policies, programmes and investments in nutrition. The initiative provides technical and financial support to national institutions with a mandate to oversee statistics and policy development so that they can host and analyse existing population-based and cross-sectoral datasets and use these to inform policy and strategic dialogue for tackling malnutrition and its consequences. Up until the advent of the SUN Movement in 2012, there had been minimal attention at global or national level to strengthen multisector nutrition data systems. Attention had hitherto focused on nutrition surveys and surveillance using mainly anthropometric measures and estimates of micronutrient deficiency.3 In 2013, the LANCET nutrition series identified ‘a lack of consistently collected data on important multisector nutrition indicators as holding back actions to address poor nutrition’.4 In parallel, sectoral information systems’ strengthening, which works towards aligning multisector data systems, have mainly focused on acquisition of technical skills and technical solutions with limited incentive for overcoming quality challenges.5 In 2014, the Global Nutrition Report called for ‘a data revolution’ recognising a huge data gap in nutrition while considering more could be done with existing data and with better use of the latest technologies.6 The NIPN initiative emerged in 2015 in large part out of these observations, together with other global nutrition data initiatives.

Since 2015, progress in establishing multisector nutrition data systems across SUN Movement countries has been uneven with the best performing countries having developed multisector nutrition action plans with associated common results frameworks.7 The SUN country dashboards have been unable to adequately tell the nutrition story, however, and serve country needs and priorities.8 Nonetheless, during this period the identified need and demand for strengthened multisector nutrition information systems had been growing.9 At the global level a need for more ‘actionable data’ and more ‘contextualised evidence’ has been recognized as key to scale-up nutrition actions and achieve national targets.10 In 2019, a DataDENT review of SUN Movement country costed plans and a 2021 review of official development assistance found shortfalls in planning and budgeting as well as donor financing for nutrition information systems (NIS).11 These reviews concluded that comprehensive national nutrition data strategies and implementation plans are needed to ensure data investments are prioritised, coherent, and coordinated within and across sectors and stakeholders.

In 2021, WHO and UNICEF issued guidance on national NIS which includes sections on ‘context’ data (nutrition-relevant multisector data), data governance and nutrition financing data.12 This guidance acknowledges the complexity of laying the ground for such information systems considering the multisector nature of nutrition. It also states that all core NIS components as defined in the guidance must be implemented.

The NIPN approach is predicated on being embedded within existing national institutions and multisector coordination systems for nutrition The platform aims to generate evidence from analysing available and shared sector data within each country, which is then used by national stakeholders for developing policy, designing programmes and allocating investments. A process described through the NIPN operational cycle consists of three elements that aim to constantly revolve and feed into each other as per the below:

-

Question formulation based on government priorities;

-

Analysis of data to inform the questions; and

-

Communication of the findings back to government.

Whilst the NIPN operational process was not new to the global health sector, its ambition was new in application to the nutrition sector as it added the complexity of working across several sectors.13

The NIPN operational cycle is supported by the national NIPN structure made up of specialists who identify priority policy questions, interpret results of the data analysis and communicate the findings. There are also data component specialists, for example within central bureaus of statistics who collate and clean the multisector data, host a central repository and carry out complex data analyses based on the priority policy questions. The operational cycle allows for the bringing together of these two specialist groups at key steps in the process, serving capacity building objectives.

During the first phase of NIPN initiative funding, there were nine active NIPNs globally in Burkina Faso, Bangladesh, Ivory Coast, Ethiopia, Guatemala, Kenya, Niger, Lao People’s Democratic Republic and Uganda. The country implementation was limited to nine countries as these provided for a wide variety of contexts for learning, considering that the original and ambitious long-term vision was that NIPN would be rolled out in other SUN Movement countries. Most country platforms only became functional between mid-2018 and mid-2019 due to the various activities and long timeframe needed to set up a NIPN at country level. The NIPN set-up abided by common features and principles and aimed to lead to a collaborative process by which the platforms could achieve a “data informed dialogue”.14 In early 2022, the NIPN in Bangladesh was discontinued due to a host of complex issues and in 2023, Zambia became a new NIPN country. In addition to the implementation in country, a global support unit was established. Initially with Agropolis International, the Global Support Facility (GSF), was responsible for developing the delivery framework, leading its implementation, providing technical assistance and coordinating the initiative between countries. As of 2020, the global support unit has been hosted by C4N-NIPN, a component of the joint-action “Capacity for Nutrition” (C4N) of the European Commission and the German Federal Ministry for Economic Development and Cooperation (BMZ), operationalised by GIZ.

Implementation of NIPN followed similar approaches and trajectories in all countries, although there were considerable differences in timelines. The country platforms are linked by common global objectives but result from extensive contextual adaptation. Thus, there is wide variation in the activities and means to achieve these. Following scoping missions to identify optimal institutional arrangements, there were often protracted negotiations and lengthy consultative processes to finalise Terms of Reference (ToRs), Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs) and contracts between the donor/s and the NIPN implementation bodies. Once the contractual agreements were in place, intensive capacity building and sensitisation of the approach with the NIPN implementing bodies was carried out. Each country then undertook its first Policy Analysis Cycle (PAC) involving multiple stakeholders in workshops and meetings to determine the policy-related questions and through a process of refinement, a short list of 5–6 priority policy questions (see table 2).

METHODS

Protocol development

The first step of the evaluation involved revising an existing NIPN logic model (theory of change) to clearly differentiate between the direct outcomes i.e., those the programme should achieve through its activities from the indirect outcomes or impact outcomes, defined as those that require the collective effort with other partners. Having a clearer and differentiated logic model was essential for the development of an evaluation research framework (RF). The RF set out fifteen research questions organized according to the OECD-DAC criteria of relevance, coherence, effectiveness, impact and sustainability.15 The RF also identified the judgement criteria and indictors to be used as well as the source/s of evidence and the study approach. Step one formed the basis of a study protocol which was shared with NIPN global and country actors to ensure clarity on the scope and purpose of the study.

Data collection

To comprehensively assess whether NIPN had contributed to indirect or impact related outcomes in addition to achieving intended results, it was necessary to review the performance of each NIPN country in detail. The evaluation adopted a case study approach to assess all nine NIPN countries. In-depth document reviews were conducted for each country and the findings were triangulated through key informant interviews (KIIs) with a range of stakeholders involved in the implementation of each NIPN.

To investigate the performance in more detail, two countries were identified as deep dive case studies (Niger and Kenya). Two N4D members spent a week in each country interviewing multiple stakeholders with a specific focus on impact evaluation questions to assess the longer-term contribution of each NIPN. An N4D consultant also visited Bangladesh which had closed early as the findings and learnings related to the reasons for its closure were needed to provide additional insights and comparisons for the evaluation.

Analysis and validation

As the analytical approach differentiated between assessing the results of NIPN (activities, outputs and direct outcomes) and assessing its contribution to indirect outcomes the evaluation originally adopted Contribution Analysis as the main analytical approach. However, during the data collection phase it became clear that the amount of evidence required to comprehensively complete Contribution Analysis was not available.

Consultation and finalisation

For each deep dive country, a de-briefing session was held to discuss initial analysis and to provide an opportunity for NIPN teams to offer additional evidence related to performance that was not initially captured. Following these sessions, a full report was prepared, and the evaluation team presented the preliminary findings to all NIPN countries and teams at a NIPN Global Gathering in June 2023.

RESULTS

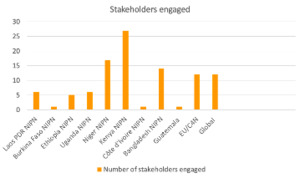

A total of 102 KIIs were conducted representing national and global stakeholders as shown in Figure 1.

Amongst the stakeholders consulted, there was unanimous agreement of the continued relevance of NIPN. NIPN’s institutional approach was also found to foster the right level of engagement for government sectors to share data and engage in policy dialogue. Setting-up NIPN took much longer than anticipated due to a variety of administrative and capacity issues. The COVID-19 pandemic also created significant delays in implementing the range of NIPN activities. Nevertheless, NIPN has shown that it can be responsive to national needs through data analysis and engagement.

Once fully established, the coherence of NIPN’s interaction between government sectors and institutions was found to be strong with some variation between countries related to exact location of NIPN within government. The platforms engaging with a wide range of sectors were seen as serving to foster data sharing, nutrition policy engagement and coordination across sectors. There were however gaps in accessing humanitarian and routine data in some countries. This related to both a lack of NIPN visibility and, in some cases, a weak data sharing culture within and across sectors for example as experienced in Guatemala and Cote D’Ivoire. Considerable variation was observed in the degree to which countries engage and collaborate with other data initiatives and the level of engagement at the global level was found to have faded away. Low engagement in relation to the SUN Movement architecture and other global data initiatives reduced the opportunities for strategic collaboration and visibility.

The evaluation found that NIPN was effective in embedding the processes and activities in national government structures and that the time spent ensuring this is a pre-requisite for a functional NIPN.

Table 1 describes the institutional arrangements of NIPN across the nine countries as well as the number of policy-related outputs emanating from the PAC.

The experience of implementing the PAC was a steep learning curve for countries but this ultimately led to more streamlined processes and increasingly useful and relevant policy brief documents.

Global guidance focused on soft skills through common process implementation and technical skills acquisition were more adjusted to national context.16

All NIPN countries have developed dashboards which act as one-stop shops for nutrition related data and allow for the visualisation of these data. Some national dashboards also contain repositories that enable others to access raw administrative and survey data for research purposes. The considerable capacity strengthening investments by NIPN has raised awareness, enhanced knowledge and skills and strengthened coalitions across sectors and other stakeholders including parliamentarians in some countries. It has also contributed to more efficient PAC processes and greater appreciation amongst decision-makers of the importance of data and evidence to inform nutrition policies and strategies. This is evidenced by the increasing demands from a diverse set of stakeholders in many countries for nutrition related questions to be included in the PAC.

NIPN’s impact is seen in strengthened nutrition tracking in many countries through a combination of re-analysis of existing data sets, improved visualisation of data on dashboards or through advocating for improved or more timely nutrition data provision. Barriers to further strengthening nutrition tracking include lack of available data and limited access to certain types of surveillance data. There is widespread recognition that NIPN needs much longer to inform and influence multisector policymaking and investments on nutrition, but there is evidence that NIPN has effectively laid the foundations to influence policy for individual sectors and multisector programming. NIPN was found to have been playing a key role in monitoring implementation and impact of national multisector nutrition plans in several countries and to have the potential to significantly impact key issues such as humanitarian and development ‘nexus’ strengthening, government and external partner financing, and climate change policy through its PAC process and evidence generation.

There was a limited focus on sustainability in the first phase of NIPN and it remains highly dependent on external donor funding. However, sustainability is a major focus of NIPN Phase two and sustainability plans are being developed in all NIPN countries with a desire to stimulate predictable government financing and to market NIPN to create greater demand for NIPN services through business case development and strategic outreach. There is a strong indication from most NIPN country teams that an externally funded third phase of NIPN will still be needed, although a third phase would allow for most, if not all NIPN functions, to transition to government resourcing.

DISCUSSION

The nutrition sector has for many decades been characterised by deficits in the data environment holding back progress in monitoring the nutrition situation and generating country-specific evidence for what works to reduce malnutrition. Global actors have long called for ‘a data revolution’ in nutrition with increased investment to fill the huge data gap while concomitantly calling to do more with existing data and to make better use of data.17 The NIPN initiative emanated from this call.

In parallel, the pivotal Lancet Nutrition series (2008)18 highlighted that just 20% of malnutrition can be addressed through nutrition-specific (largely through the health sector) activities with the remaining 80% requiring nutrition-sensitive approaches from multiple sectors such as agrifood system, education and social protection. This stark fact was the major impetus for the creation in 2012 of the SUN Movement predicated on the need to scale up multisector programmes, thus reviving the need for multisector data and analysis. As the SUN Movement gained momentum with over 60 countries eventually becoming signatories, countries developed multisector policies and strategies for nutrition, to which were adjunct action plans with results frameworks to help monitor programme implementation. These frameworks’ functionality varies enormously at country level. It reflects the profound challenges in the data environment including a lack of investment as well as the poor availability and quality of data faced by most sectors19 coupled with the added complexity that nutrition is a multisector concern. Moreover, sector information systems on which NIS rely do not necessarily have a nutrition lens20 and global guidance for multi-sector NIS came about only very recently.21

Over the years of implementation, NIPN countries have shown what it is possible to achieve with existing data. They have produced numerous high quality policy briefs, technical reports and research studies22and there has been considerable effort to ensure these are easily accessible on NIPN country websites. They have shown, despite a slow start, to be responsive to national needs through responsive data analysis and engagement. There are country examples where the platforms have been able to focus on emerging issues23,24 and generate dialogue on policy issues or influence multisector planning.25

Strengthening the indicators collected by nutrition-sensitive sectors and implementing the operational cycle process have led to nutrition stakeholders identifying key policies questions related to nutrition and multidisciplinary teams including data specialists addressing those through analysis and policy briefs. This has a significant impact on creating the enabling environment to influence policies. The fact that the PAC question analysis are formulated by specialists close to policy, programme and investment decisions and uses national data provide national context-specific analysis and findings. Beyond the fact that it reinforces the confidence of policymakers in the analysis and creates national ownership, it responds to the global call26 for more contextualized evidence which is key to tailor and adjust nutrition actions at national and subnational level.

NIPN have also shown that it is possible to operationalize a multisector approach over data analysis and data use in spite of the sensitivity that data sharing can represent for any sector. Countries have made progress in compiling multisector nutrition data dashboards and repositories effectively providing one-stop shops that help visualise data trends, progress against targets and unrestricted access to the data sets.27 Most country platforms have been positioned to monitor multi-sectoral nutrition actions plans, and as such, have responded to crucial data and analysis gaps and helped serve an operational and advocacy role for the revision of those plans and related RF. The platforms have enabled raising awareness of nutrition’s role in sector activities as well as increasing capacity to identify nutrition-sensitive indicators and monitor these in sector plans and policies as well as national multisector nutrition plans. Thus, in many regards, the platforms’ implementation has provided the means to operationalise a multisector approach.

Given the constraints over data management (quality, availability, access and capacity and data sharing for decision-making), achieving the operationalision of a multisector approach for data analysis and use is a notable achievement. However, NIPN analysis and support to decision-making as well as its ability to respond to the stakeholders’ demand will always be subject to the reality of data quality and availability issues. These limitations are beyond NIPN’s remit and depend on complementarity with other data initiatives. Furthermore, NIPN outputs and achievements offer the potential for a more pro-active role in identifying specific data gaps and issues with more granular precision for specific contributing sectors and to advocate for increased investment in nutrition data.

NIPN is unique from a political economy perspective in that the approach has secured government ownership from the beginning by embedding the NIPN processes within existing national structures.

Access to multisector data (a prerequisite for an effective NIPN) and the ability to both draw upon and influence the perspectives of decision-makers in government is clearly a function of NIPN’s institutional location within government, which also allows for cross-sector convening authority and influence as well as proximity to decision-making. In many respects, NIPN has begun to succeed where many other data initiatives have failed. Unfortunately, history is littered with data initiatives that have not sustained precisely because they have not paid enough attention to institutional location and concerns.28,29 Indeed, the only NIPN programme which has not sustained is Bangladesh where NIPN functions were driven by external partners and budgetary decisions were outside the remits of national institutions and stakeholders.

The government ownership of NIPN and its institutional positioning is beginning to reap important benefits. It has enabled consistent and concerted efforts to sensitise and build capacity of government sectors to nutrition, providing them with the knowledge and means to improve nutrition-sensitive planning and monitoring.30 It has also helped government actors across sectors to better utilise evidence to drive and support policies. It is also enabling governments and country stakeholders to control the research agenda and is empowering governments through data analysis to address emerging issues such as the need to mitigate climate impacted areas of a country, and where it is operating in fragile contexts to strengthen the humanitarian, development and peace nexus.31

The location of the analytical function and coordination mechanism for the PAC matter as much as the process behind it. NIPN brings together national data specialists, some of whom are close to policy, programme and investment decision-making in nutrition around common issues. With the NIPN process, the policy group are intimately involved in both the question formulation process and understanding the significance of the NIPN analysis to address the questions. This has led to greater awareness and interest in data while the data specialists and sectors have had a space to communicate more over data limitations. In addition, the fact that the PAC question analysis uses existing national data has engendered greater confidence amongst policymakers in the analysis. As a result, NIPN implementation has helped shift the ‘data focus’ from their production (often in the hands of data specialists) to their use (by bringing those interested in analytical findings) into the process.

Although most stakeholders interviewed agreed that it is too early to see a policy impact of NIPN in large degree due to the lengthy cycles of policy processes and lack of appropriate metrics to measure it, a common view is that the NIPN approach has created an enabling environment for policy impact which will become more evident by the end of phase two.

The increasing visibility and utility of NIPN nationally (it has less visibility globally) is leading in turn to an increased likelihood of some degree of sustainability if international fundings is reduced or ceases. This is evidenced by a concerted focus by NIPN in phase two (ending in 2025) to draw up sustainability plans based on maintaining a streamlined NIPN and through a variety of institutional and planning mechanisms, which will ensure a minimum level of government resourcing. This national level of ownership and sustainability is the ultimate goal which so many programmes conceived by development actors often fail to achieve.

CONCLUSIONS

NIPN is one of a few data focused initiatives with important lessons for the substantial number of countries globally that have high burdens of malnutrition, escalating fragilities due to economic shocks, climatic events, protracted conflicts and other threats to nutrition security and people’s resilience. Countries with high burdens of malnutrition typically have low levels of government revenue and thus, formulating the right policies and strategies as well as developing coherent multisector action plans to reduce malnutrition requires a prominent level of data oversight to monitor progress and to generate ongoing analysis to inform national and sub-national decision-making. Countries will not reach global and national targets without better data and stronger evidence informing priorities and programme actions.

Given the need for stronger data, analysis and evidence to inform decision-making and interventions that tackle malnutrition, the NIPN approach merits expansion to other high burden and fragile country contexts.

Acknowledgment

This study and article were funded by the European Union (EU) and the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development of the Federal Republic of German (BMZ).

The views expressed in this publication are those of the study author(s) and not necessarily those of the EU of BMZ. We are grateful to the country NIPN teams for sharing their expertise and for their active participation in the study.

Ethics statement

Ethics approval was not required for this study although N4D ensured all participants in the study pre-signed a privacy protection clause before participating in the study and were ensured anonymity throughout.

Funding

This study was commissioned by the European Union (EU) and the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development of the Federal Republic of German (BMZ).

Authorship contributions

CD and JS conducted the study and led on the writing of this manuscript. PG, BB, LB provided detailed review and additions to the first draft version of the manuscript. EO, IK, JG, SK and MB reviewed the draft version and provided country specific inputs. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure of interest

The authors completed the ICMJE Disclosure of Interest Form (available upon request from the corresponding author) and declare no relevant or conflicted interests.