The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) define ambitious targets for improvements in global maternal, newborn, and child health (MNCH) outcomes by 2030. However, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) currently falls short of these health goals. Its maternal mortality ratio is estimated at 547 deaths per 100,000 live births1 compared to the global target of under 70 per 100,000 live births,2 with comparable shortfalls in the neonatal3 and under-five4 mortality rates. Behind India, Nigeria, and Pakistan, the DRC ranks fourth among the eight countries accounting for over 50% of global maternal deaths.5,6

Over the past several decades, the DRC has experienced continuous violence and conflict, political and military unrest, frequent mass displacement, economic disruptions, extreme poverty, food and water scarcity, epidemic outbreaks, unmet physiological and safety needs, and disruption to the health system.7–13 In response, the government emphasizes providing minimum security for the most vulnerable populations, including access to healthcare and social protection.14

MNCH services – including antenatal care (ANC), birth attendance by a skilled personnel, and integrated management of childhood illnesses (IMCI) – are effective in reducing maternal and perinatal mortality.15–20 However, UNICEF reports that both birth attendance21 and antenatal visits22 by a skilled personnel are below global averages in the DRC. The availability of MNCH services is inconsistent across regions,10 and there are rural/urban disparities.3 Coverage estimates vary over time, across indicators, and by region.13 There is little evidence about how services are delivered to women and children in a humanitarian context.23 Overall, there are gaps in knowledge about MNCH service coverage and trends across the DRC.13 The DRC’s second demographic and health survey (Deuxième enquête démographique et de santé, EDS-RDC II 2013-2014) is often cited, but it does not capture recent trends in MNCH morbidity, mortality, or service availability.5

METHODS

Study Design

This systematic review aimed to synthesize information on the availability of MNCH services in the DRC, focusing on system-level barriers and facilitators. The authors followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, which outline methods to systematically identify, screen, and assess literature in a review.24,25 Authors included both qualitative and quantitative studies and did not conduct a meta-analysis.

Search Strategy

Authors searched PubMed and Google Scholar using keywords to capture MNCH in the DRC and multiple dimensions of supply-side service availability. We received internal review and input on the search strategy throughout the study process. We consulted experts at Abt Global, including various researchers and librarians to determine and refine the databases, keywords, and combinations. There were no conflicts to report in determining the search terms – all revisions and suggestions were incorporated. Among the accepted suggestions by experts in the DRC was adding integrated case management (ICMI and ICCM) to the PubMed search terms to capture additional MNCH activities and studies. The final search terms are in Table 1.

We identified grey literature through the World Bank, World Health Organization (WHO), Ministry of Health, and United States Agency for International Development (USAID) websites, in addition to a Google search. Searches were completed in June 2023.

Eligibility Criteria and Study Selection

The review focused on factors impacting supply-side MNCH service availability in DRC. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarized in Table 2.

Non-duplicative search hits were screened against the inclusion criteria. For articles that met the criteria, a researcher reviewed the abstract to determine relevance based on a set of supply-side factors adapted from the World Health Organization (WHO) Service Availability and Readiness Assessment (SARA).26 Based on the SARA indicators, authors included health infrastructure (including geographic density of health facilities and accessibility); health workforce; and facility readiness (i.e., availability of amenities, medicines, and equipment). The authors added the role of conflict in response to the DRC context and explored health financing and governance given their inclusion in policy documents, such as the National Health Development Plan.14

Data Extraction and Synthesis

We developed an abstraction tool using Microsoft Excel to extract and organize data from each included article. The initial tool was piloted prior to article review on several articles about MNCH but outside the DRC scope. However, tool development was iterative, with the authors initially collecting additional data elements and streamlining the scope throughout the abstraction process as the key themes became clear through their presence in the included literature. When the categories of the tool were finalized through collective agreement by the research team, each abstraction was confirmed against the original article to ensure that all relevant data were captured. Collected data included: title; author; document type; geographic focus; barriers and facilitators to service availability; and key themes addressed. One researcher completed the abstractions, and a senior researcher reviewed abstracted information for accuracy and clarity.

Authors manually synthesized extracted data. The analysis used a narrative approach to compile textual findings from multiple sources and develop a cohesive presentation of current knowledge and key themes.27 Initial themes were based on the WHO SARA indicators outlined above and iteratively adapted in response to the available information.

The authors also assessed the quality of all included literature using the Quality Assessment with Diverse Studies (QuADS) tool.28 This tool was developed to assess methodological and reporting quality across study types and has strong reliability and validity.28,29 For all studies, the authors classified study quality as strong (score 27-39), moderate (score 14-26), or weak (score 0-13).

RESULTS

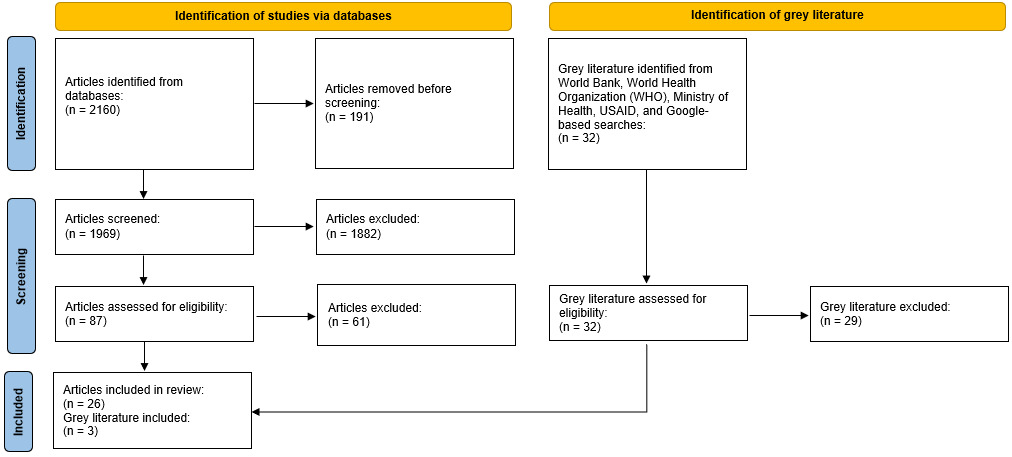

The initial search generated over 2,000 articles. Following de-duplication and screening according to the inclusion criteria listed in Table 1, 87 articles were selected for full technical review (Figure 1).

After full article review, 26 articles were included in the narrative synthesis. The articles were diverse regarding study design, MNCH services, and geographic focus. Three grey literature materials were included in the review. The included studies are presented in Table 3. For individual-level quantitative studies, the median sample size was 1380 individuals (IQR=1180-6947). For quantitative studies at the facility level, the median sample size was 77.5 facilities (IQR=58-321). For included qualitative studies, the median sample size was 30 participants (IQR=30-84). Given the diversity of included research, not all reported sample sizes.

Assessment of Study Quality

Of the 26 studies, none were assessed as “weak,” 13 as “moderate”15,23,30–40 and 13 as “strong”.36,41–52

Study Location

All documents included the DRC. Six had a multi-country scope. Nine had a national focus, and 11 were regional. The regional publications focused on eastern DRC, the provinces of Kasai, Kinshasa, Kwango, Kwilu, Haut-Katanga, Kasai-Oriental, Ituri, Equateur, North and South Kivu, and the cities of Kabinda and Lubumbashi.

Services Studied

Articles referenced both basic and emergency services, including childhood vaccination, labor, Cesarean sections, ANC, emergency obstetric and newborn care (EmONC), midwife services, antenatal ultrasound screening, pre-eclampsia screening and treatment, antenatal syphilis screening, nutrition, and management of children with severe disease.

Factors affecting MNCH Service Availability

This systematic review identified several themes with implications for the availability of MNCH services: (1) facility readiness to provide health services (e.g., adequate equipment, supplies, and infrastructure); (2) human resources for health (HRH) capacity and training; (3) geography of services/facilities and transportation; (4) presence of conflict; (5) financing; and (6) governance. The findings are discussed in detail below according to these themes.

Facility Readiness

Eighteen studies identified supplies, equipment, and/or infrastructure at health facilities as critical factors affecting MNCH service availability.15,23,30,31,33,34,37–39,41–45,47–50

The availability of vaccines, medicines, and supplies was hindered by low supply, poor management, procurement from various sources, weak transportation systems, delivery delays and logistical challenges, weak cold chain systems, lack of access to stable electricity or equipment, low staff capacity, and poor distribution resulting in overstocking at the center and stockouts elsewhere.43–45,48,49 Conflict exacerbated issues given looting, damages, additional procurement and delivery delays, and frequent stockouts.34

The availability of essential medicines and vaccines varied across the DRC and was often cited as low.15,23,33,39 Providers experienced inadequate or subpar supplies for diagnosis and treatment of antenatal syphilis43 and hypertensive disorders.30 Few health facilities had magnesium sulfate (36.2%), calcium gluconate (31.0%), aspirin (29.3%), methyldopa (18.9%), nifedipine (15.5%), and hydralazine (6.9%).47 However, parallel supply chains, buffer stocks, establishment of MNCH care units, and decentralized commodity storage facilitated medicine/supply availability.34,42–45,49

In Kinshasa, all facilities had stethoscopes and blood pressure machines.47 A study in Kwango and Kwilu found that adult weigh scales, delivery tables, blood pressure devices, stethoscopes, and delivery kits were widely available, with a frequency of over 75% overall.33 However, umbilical-cord-clamping materials were available at only 33.4% of facilities and 40% of primary health centers in Kwilu, with availability varying significantly between provinces.33 A cohort study in Lubumbashi found that maternity kits were often inadequate, even in reference hospitals.15

Weak infrastructure also contributed to poor quality and availability of health services.49 Approximately 80% of facilities surveyed in Kasai Province had insufficient infrastructure, limiting the availability of emergency obstetric services.41 In a study of Kwango and Kwilu provinces, drinking water was available in only 25% of all facilities, while electricity was available in 49.2% of labor rooms and 67.6% of delivery rooms.33 Gaps in electricity availability and equipment servicing were persistent barriers to the use of equipment such as antenatal ultrasound machines31 and Haematocric centrifuges43 for testing and diagnosis. However, researchers in one study installed solar panels at health facilities to provide necessary power.31 Carter et al. (2019) found that, despite supply deficiencies and poor facility conditions, EmONC was generally available in rural DRC.33

Human Resources for Health

Twenty articles discussed HRH in relation to MNCH services, with emphasis on HRH availability, capacity, compensation, turnover, motivation, and training.23,30,31,33,34,36,38–47,49,50,53,54

The DRC’s MNCH needs outweighed the capacity of trained health workers.41,42,46,53 There was only one midwife per 20,000 people.53 Shortages and poor HRH distribution hindered access to services, especially in rural and conflict settings.43,46,50 In one study, interviewees noted the lack of female providers,43 though a community health worker (CHW) study found a higher proportion of female than male providers.40

Formal training and knowledge of health workers was lacking.23,41,43,50,53 Sharma et al. identified an inadequate number of skilled providers – including surgeons, anesthesiologists, obstetricians, and lab technicians – as a barrier to EmONC availability in the DRC.50 In Kasai province, nearly half of providers were low skilled (nurses’ level A2), and only 18% were trained in reproductive and MNCH.41 Only 12.5% of children with severe disease were seen by a provider recently trained in IMCI protocols.38 Another study noted poor knowledge about prevention and management of pre-eclampsia, despite 91% of providers having diagnosed severe pre-eclampsia correctly.47

Midwifery education programs exist, but quality is lacking due to limited teaching equipment and educators’ low academic qualifications.36,45 Ongoing training opportunities are limited.45 Where providers were aware of training and continuing education opportunities, availability of training spots was limited, and providers had reservations about the system for filling available spots.43 In conflict areas, health facilities under pressure to fill vacancies may employ “rapidly trained agents” without full training.23

Estimates of CHW attrition – workforce reduction usually due to resignation – are as high as 40%, though the estimate may not be reliable.30 Limited management and supervision, staff turnover, poor work environments, high workloads and cognitive load, limited opportunities for career advancement, and conflict impeded the ability of community health workers (CHWs) and other healthcare providers to provide MNCH services.23,34,38,40,42,46,50 On average, a CHW was responsible for 171 children in the DRC, higher than four of the six other African countries studied.44 Irregular, fragmented, or inadequate compensation was repeatedly cited as an HRH barrier.23,38,46,50,54 Conflict also deterred new health workers, hindered transportation and access to populations, and increased stress and fear among health workers – all of which interrupted service delivery.23,34

However, several factors contributed to retention and motivated health workers to continue providing services: loving one’s work, investment in the community, good relationships at work, and professional satisfaction.53 Swanson et al. (2017) identified dedicated and motivated health workers as a facilitator of service availability in Equateur Province.31 The presence of CHWs and other providers (e.g., nurses, midwives, pharmacists, and nutritionists) improved service delivery by expanding access to care, building trust with patients, and contributing to equitable distributions of health services and benefits.42,44 In addition, the integration of mobile technology mitigated HRH barriers such as travel, supervision, and payment logistics.42,44 Several strategies anticipated and reduced HRH shortages, including task shifting to expand the responsibilities of local, rapidly trained, or lower-level staff; training agents to take on additional roles, including supervision; and expanding training.34

Geography and Transportation

Fourteen studies discussed geographic access to care as a determinant of MNCH service availability.23,30,31,34,35,37,38,41–45,47,48

Two studies mentioned rural/urban divides in healthcare availability.35,37 Ashbaugh et al. (2018) found children in rural areas were less likely to receive proper vaccinations than those in urban areas: 24% of children were unvaccinated in urban areas compared to 32% in rural areas (p < 0.0001).37 A Haut-Katanga spatial access analysis identified the uneven distribution of facility types and the concentration of private facilities around Lubumbashi.35

Seven studies identified distance to a health facility and travel conditions (such as poor road conditions, rainy season, insecure areas, and challenging terrain) as a barrier to MNCH service accessibility.23,31,35,41,43–45 In the Kasai region, only 54% of the population had geographic access to MNCH services, and approximately half of the population had a walking commute of over one hour.41 Acharya et al.48 found that 41.2% (95% CI 35.88, 42.69) of mothers experienced challenges accessing healthcare due to distance, and that willingness to immunize children was hindered by long distances and high travel costs.48 Insecure settings exacerbated travel concerns.34

Furthermore, geographic barriers and transportation issues hindered referrals to higher levels of care, such as referral hospitals.31,35,44 Over half the Haut-Katanga population needed to travel more than four hours to reach a referral hospital or facility.35 Referral transport systems were rare, particularly in conflict settings such as North Kivu.34 As less than 25% of primary care facilities had access to an ambulance,43 referring preeclamptic women to hospitals was challenging.23,43 Geographic inaccessibility of referral facilities may also contribute to the low referral rate for IMCI cases in the DRC,38 which falls under the recommended referral rate.30

Strategies to facilitate access included bicycle trailers in the Equateur Province to transport pregnant women and new mothers without access to a vehicle31 and provision of ambulances and motorcycles as emergency transportation in Kwango.42 Health posts and mobile clinics were used to mitigate transportation barriers and reach populations generally,34,35 while maternity waiting homes or “Binyolas” allowed pregnant women in conflict zones to travel to a facility during times of relative peace and stay near the facility until labor.34 Additionally, some facilities reduced travel requirements by distributing “security drugs,” a supply of preventative drugs for chronic conditions.34

Conflict

Seven articles included the effect of conflict on the availability of MNCH services.23,34,37,44,48,52,53

Conflict decreased the availability of HRH in North and South Kivu, limiting access to the population, causing fear and anxiety, creating difficult working conditions, and disrupting training and supervision.23,44 Conflict zones were characterized by deficits of equipment and supplies due to pillaging, targeted attacks, and transportation difficulties.34,44 Reduced investment and procurement opportunities also reduced facility readiness, as did the strain on health facilities and supplies caused by internally displaced people.23 Militias and political instability may explain poor immunization coverage in Tanganyika Province.48 Bogren et al. (2020) also suggest conflict and the resulting strain on the health system were responsible for poor healthcare quality in Maniema and Kasai.53

However, there were mixed results for conflict-affected areas within provinces, with some displaying higher healthcare coverage than stable areas.34,37,52 A study of RMNCH service coverage found increases in coverage over the course of the study in North and South Kivu.34 Health facility data showed a small negative correlation between insecurity and preventive service coverage within provinces overall.23 Furthermore, Schedwin et al. (2022) found that conflict alone was a poor predictor for child health – the odds of coverage for indicators of preventive care (e.g., skilled birth attendance, exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months, kangaroo mother care) were higher in conflict-affected provinces for 13 indicators, compared to one indicator that had higher odds of coverage in non-conflict provinces.52 A childhood measles vaccination study reported that residing in a province experiencing displacement due to conflict was predictive of increased vaccination.37 Authors attributed the correlation to the increased number of aid workers providing essential services, noting the finding was consistent with other published studies showing that reactive campaigns in high-risk areas tended to improve vaccination levels.37

Financing

Twelve sources referenced health financing.30,31,38,41,43–45,48–51,54

The DRC has low heath expenditure per capita when compared globally, across low and middle income countries (LMICs), and within Africa.49,54 Per capita health expenditure in the DRC is less than 10% of the average for the rest of sub-Saharan Africa.51 Less than 10% of per capita health expenditure originates from government, while external aid accounts for about 39% of total health expenditure.49 Estimates of out-of-pocket or household spending range from 40% to 50% of total health expenditure.49,54

Health financing was identified as a major bottleneck for skilled care at birth, basic and comprehensive emergency obstetric care, and essential childbirth services.50 Clinic administrators, healthcare providers, and pregnant women in primary care clinics interviewed in Kinshasa identified cost as a barrier to care.43 For example, the USD 10 vaginal delivery cost and USD 50 cesarean delivery costs posed a significant barrier to care seeking.31

A lack of adequate, multi-year, predictable financing inhibited service scale-up.50 Flexible and longer-term funding was especially important in areas prone to conflict.44 Nationalization and program scale-up may help programs including IMCI gain efficiency given the relatively higher recurrent costs per capita of the sub-national IMCI program in the DRC compared to national programs in Malawi and Senegal.30

Support from donors ameliorates immediate barriers by reducing patients’ out-of-pocket costs.31 For example, a United Kingdom Department for International Development grant reduced the cost of MNCH services by 80% for hospital patients in Equateur Province.31 However, support from external funders may be unreliable and lead to governance challenges34,39,45 – see below.

One facilitator of financial access to care is government commitment to reducing out-of-pocket costs, evident in commitments to Universal Health Coverage (UHC).14 A key goal of UHC is reducing financial barriers to care so the whole population can access affordable preventative, curative, and rehabilitative care.51 Following the DRC’s adoption of UHC policies, there were slight improvements in financial risk protection indicators.51 However, adopted policies increased healthcare access for the wealthiest quantile without meaningful progress for the rest of the population.51 The authors of this study suggest political prioritization, including more structured and operational strategies for achieving UHC, in addition to more funding to continue reducing financial barriers to care.51

Provider payment system reform, such as Performance-Based Financing (PBF), has also shown some promise.49 In one example, contracted health facilities received payments for service quantity (fee-for-service for reproductive and MNCH services) and quality (bonuses based on a quality checklist and in proportion to the quantity of services).49 Baseline to endline comparisons suggest substantial coverage increases for several MNCH services following implementation of PBF in 11 provinces in 2016.49

Governance

Eleven articles mentioned the role of governance in the context of MNCH service availability.23,31,34,39,43–46,48,50,53

Clear and consistent political support for MNCH services improves service coverage and delivery,44 while inconsistent funding, coordination, and political prioritization are barriers.23,31,39,48 A related hindrance is lack of policy action.53 Policies did not always translate from local to central levels and vice versa; for example, frontline healthcare workers in Adja and Aru repeatedly suggested central government action to ameliorate regional HRH shortages but felt central government was not responsive to local needs and suggestions.46

Leadership fragmentation impacts service delivery, contributing to vertical program silos focused on certain health condition(s). While vertical programs provide strong technical and financial control, they can lead to duplication and increase costs unless resources and personnel are shared.55 District level facilities faced pressure to implement multiple vertical programs but lacked sufficient authority, capacity, and resources to do so.39 In addition, vertical programs overlapped with and hindered delivery of more comprehensive IMCI programs.39

External actors – including private organizations, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), donors, and UN agencies – had a strong presence in some regions, which affected MNCH service delivery.23,48 These organizations contributed to improved services – the historical presence of NGOs in North and South Kivu may explain higher vaccination rates.48 However, the presence of non-governmental stakeholders also contributed to funding fragmentation34,39 with externally backed health facilities able to provide more and higher quality services than those relying primarily on out-of-pocket expenditure.23 External funding also influenced priorities, resulting in emphasis on donors’ compared to local priorities23 and creating confusion among frontline health workers when priorities and strategies did not align.39

However, governance reforms catalyzed MNCH coverage.39,43,46,53 Clear collaboration mechanisms and coordination between regional and national government and non-governmental actors was a facilitator to service availability.46,53 Horizontal integration of programs leveraged existing resources and aided service availability, as did integrating existing systems, including ICMI, to strengthen capacity.39 The existence of national guidelines and public health initiatives also facilitated the availability of high quality MNCH care.43

DISCUSSION

Our review highlights many factors affecting consistent and equitable service availability in the DRC. The most prevalent of the six themes were HRH (20 articles) and facility readiness (18 articles). Fewer articles discussed the role of conflict, though results were notable for their mixed findings and relevance to certain regions in the DRC. All six key themes included both facilitators and barriers, indicating significant challenges to care accessibility but also promising strategies and trends.

Barriers

The most prevalent of the six themes were HRH (20 articles) and facility readiness (18 articles). Articles included in our review focused on multiple aspects of HRH. There was general alignment among articles regarding HRH, and barriers included insufficient staff, poor distribution, low and unpaid salaries, limited career advancement, inadequate training, and turnover. There were no direct conflicts among included articles except the prevalence of female providers. This dissonance may be explained by variation in female representation by provider type, as the literature indicates that more men than women work as doctors and nurses, but more women than men work as midwives.56 Our findings align with other literature identifying HRH shortages and rural-urban disparities in the DRC56 and insufficient training, high workloads, low supervision, inadequate salaries, poor working conditions, poor distribution, and low motivation among MNCH personnel in LMICs.57 The quality of cumulative HRH articles was high, with a median assessed quality score of 28 (IQR=21-31).

Similarly, the median quality score for facility readiness articles was 26 (IQR=21-30), corresponding with the upper limit of our moderate quality category. Articles were generally consistent in finding low or varying availability of vaccines, medicines, supplies, and infrastructure, though there were differences across supply-types and regions. Future research on facility readiness across regions could better identify the scale and consistency of subnational differences. Specific supply-side challenges included lack of essential medicines and supplies, stockouts, weak cold chains, challenging procurement and delivery logistics, and infrastructure concerns (e.g., water and electricity availability). These findings are consistent with literature citing low service readiness in the DRC58–60 and other LMICs.61,62

With a median quality score of 22 (IQR=21-30), the 14 articles on geography and transportation were assessed to have somewhat lower quality than the HRH and facility readiness groups. However, the results of included studies largely aligned, with half of articles mentioning travel conditions and distance to a health facility as a barrier to service availability and the others noting consistent findings. These findings align with other literature citing low healthcare accessibility due to geographic and transportation constraints in the DRC.63

While only seven articles discussed the role of conflict, results were notable for their mixed findings and relevance to certain regions in the DRC. The median quality score for these articles was 22 (IQR=21-30), with all assessed as moderate or high quality. The effects of conflict on MNCH service availability were complicated in the included literature, with some authors reporting null or positive effects on service availability in conflict zones34,37,52 and others noting conflict-related barriers to service availability23,44 and positing conflict hindered MNCH services.48 Studies in other conflict areas have also reported unique barriers to access in conflict zones (e.g. security issues, workforce challenges, inconsistent financing) while finding improvements in reproductive and MNCH service coverage after humanitarian assistance efforts, despite the initiation of conflict.64 Future research could further elaborate on the role of humanitarian efforts and other facilitators to health coverage during conflict.

The group of articles discussing financing (median 30, IQR=21.5-33.5) and governance (median 30, IQR=21-32) had the highest median assessed quality scores. Among financing sources, all were consistent in identifying health expenditure, financings, and/or out of pocket costs as challenges. These findings align with other literature about the DRC and resource-limited settings, which show limited healthcare access and utilization.65 The 11 governance articles also aligned, with most identifying lack of policy support and action and coordination challenges among various actors. Similar governance and coordination challenges appear in the literature for nearby countries, including Kenya.66

Notably, barriers across the key themes highlighted uneven service availability, uncertainty, and logistical challenges. In addition to identifying specific challenges within the themes, this review revealed interconnectedness between themes. Many challenges were identified across multiple themes, revealing the complex web of barriers impacting care. For example, conflict exacerbates issues with adequate HRH, facility readiness, consistent financing, and geographic access; it deters and hinders providers,23 disrupts supply chains and infrastructure,34 interrupts financing,23,44 and makes traveling to facilities more dangerous.34 Facility readiness and geographic accessibility are affected by insufficient and poorly distributed HRH,47 while lack of government prioritization and financing exacerbates HRH training and retention challenges and medicine/supplies procurement and distribution.46,49,50

Facilitators and Recommendations

The review found that solutions and facilitators were also multifaceted and interconnected. Identified facilitators may provide insights for policy and programs functioning in the DRC. Facilitators of medicine/supplies availability included parallel supply chains, buffer stocks, and decentralized commodity storage.43–45,49 To increase service availability, these successful strategies should be replicated where possible. Literature suggests that supply chain innovation and optimization can mitigate supply chain issues and reduce costs at the health zone and health facility levels in the DRC.67 Facility readiness strategies can be paired with plans to mitigate transportation and geographic challenges. Practitioners may consider the use of bike carriages,31 motorcycles,42 health posts and mobile clinics,35 to facilitate geographic access to healthcare and strengthen referral networks. Where the health system infrastructure is weak, adaptable approaches including the use of solar panels can provide necessary health facility capabilities.31

Despite staffing and retention challenges, the presence of CHWs improved service delivery,42 and dedicated staff contributed to successful implementation of new technologies and services.31 These findings reinforce the importance of dedicated HRH. Retention was driven by motivating factors including positive perception of work and investment in the community.45 HRH recruitment and retention strategies should build on these factors. Recruitment within underserved communities could ameliorate personnel shortages in conflict zones and rural areas, while emphasizing the positive impacts of the work may bolster retention. Other research supports this approach, showing midwives and other health service representatives suggest recruitment and retention strategies like recruitment from rural areas and training activities and schools in rural areas46. Technology can alleviate persistent logistical challenges with travel, supervision, and payment42,44 and address recurrent HRH challenges. Mobile health technology interventions have been adopted for frontline workers in some contexts.68 However, some literature cautions that there is little significant evidence on the effectiveness of mobile health supervisory techniques for CHWs, and suggests adapting more evidenced strategies such as external, community, group, peer, and dedicate supervision to the local context.69,70 Addressing limitations with quality and availability of training/education opportunities may facilitate a longer-term workforce boost by increasing the number of trained personnel and improving career prospects. Some examples in the literature suggest a training of trainers approach, such as a series of three-day workshops in the Philippines that trained 112 trainers, who subsequently trained 281 skilled birth attendants and significantly improved service availability.71

While the effects of conflict on MNCH service availability were mixed in the literature, the availability of some services may be enhanced by the concentration of aid and non-governmental organizations in conflict zones.37 Building on governance facilitators such as coordination mechanisms between actors45,46 could expand the potential of both government and non-governmental actors across the country in conflict and non-conflict settings. Lessons learned from health sector and aid coordination in Ethiopia between 1990 and 201572 and Rwanda73 could guide efforts. This collaboration is especially important for health financing, where donor support31 and flexible, long-term funding can improve services and availability.44 Innovative funding models may also facilitate access – for instance, pay for performance models may increase the availability of medicines and supplies, as in Tanzania74 and system-wide reforms including flat fees, additional health service financing regulations and rationalization can increase access to quality care.75 Other service availability drivers – national guidelines,43 sustained political support,44 UHC policies,51 provider payment reforms,49 and horizontal integration efforts39 – also point to the importance of cohesive, integrated health system strengthening approaches.

Limitations

There were several limitations to this study. The authors synthesized documents about a wide range of MNCH services and therefore the results may not be generalizable within services. Furthermore, authors focused on the determinants of supply-side MNCH service availability and did not consider demand-side factors or quality of care.

CONCLUSIONS

This systematic review provides a synthesis of six key themes affecting supply-side MNCH service availability in the DRC. The Government of the DRC, supported by its technical and financial partners, has invested significantly in the availability of MNCH services. However, the country faces substantial barriers to supply-side MNCH service availability, and progress towards the SDGs and better MNCH outcomes will not occur without investment in health financing, technical skills, infrastructure, and education. Furthermore, there were few studies that showed the link between service availability and quality of care. Future research should consider quality of care and demand generation, in addition to service availability, to support health system strengthening and health service coverage efforts.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Richard Matendo for his leadership of USAID IHP. Special thanks to Christine Potts and Erin Mohebbi who contributed to the conceptualization; Corrine Tessin who contributed to the analysis; and Tess Shiras, Alison Cooke, and Bettina Brunner for their contributions as reviewers.

Disclaimer

This journal article is made possible by the support of the American People through USAID. The authors’ views do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID.

Ethics statement

This study was exempted by the Abt Global Institutional Review Board on April 25, 2023.

Funding

This research was funded by United States Agency for International Development (USAID) in accordance with the Integrated Health Program. Contract No: AEP-C-72066018C00001.

Authorship contributions

FP, NE, and members of the IHP project team conceived the study and initiated the study design. MH conducted the initial searches. RD, FP, and AD refined the scope and conducted additional searches. RD, AD, AC, and CP completed data extraction. Data analysis was conducted by RD and AD. The manuscript was drafted by RD, with input from FP, AD, LB, NE, JF, MH, AC, and CP. All authors take responsibility for all aspects of the work leading to the submission and content of the paper.

Disclosure of interest

The authors completed the ICMJE Disclosure of Interest Form (available upon request from the corresponding author) and do not have relevant interests to disclose.

Additional material

The article contains additional information as an Online Supplementary Document.

Correspondence to:

Rani Duff

Abt Global

6130 Executive Blvd, Rockville, MD 20852

USA

Rani_Duff@AbtAssoc.com